As a researcher, I feel privileged to have participated from the time this disease first appeared through seeing an effective tool developed such as current vaccines.

Younger veterinarians only know PCV-2 as one of the vaccinations routinely administered to more than 95% of animals, but those of us who were involved since the onset of the disease still remember what it taught us: Control of the PCV-2 infection upon implementing the use of the vaccine put an end to the doubts that there were about the central role that PCV2 played in this pathology, but we are dealing with a multifactorial disease where environmental conditions, density, and especially genetics played a very important role.

Has the epidemiology of PCV-2 changed due to the widespread and continuous use of the vaccine?

Yes, we must consider that the vaccine has proven to be a highly effective tool and is used on more than 90 -95% of farms in European countries, the USA, Canada and in many others.

But in biology, always doing the same thing sometimes doesn't yield the same results.

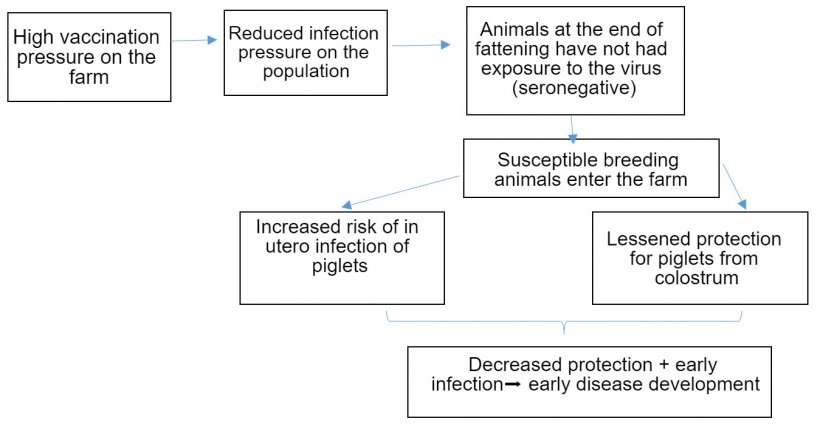

Continued vaccination on farms has led to a reduction in infection pressure. With less virus circulating, some animals reach the end of the fattening period still seronegative. If we consider that this same situation can occur in replacement gilts, the % of susceptible animals in the population is increasing. These susceptible females cause us two main problems:

- Their piglets are at a greater risk of PCV-2 infection in utero or around the time of farrowing.

- Those females provide less protection for their piglets in the colostrum.

The combination of these two facts, means that a % of piglets are already infected at 3-4 weeks, which is when many farms vaccinate their piglets against PCV-2. In these cases, vaccination is being done too late, and some animals will develop clinical disease early on (6-8 weeks of age). It should be noted, however, that this situation has been observed on only a few farms as the number of farms where porcine circovirus is seen despite having vaccinated is very low.

The widespread use of PCV-2 vaccine has led to a change in the epidemiology of the virus and in the clinical presentation of the disease on some farms.

Figure 1: Development of PCV2 infection epidemiology in the context of routine vaccination.

These problems are not exclusively limited to the offspring of gilts. If we take samples from different aged breeding females, we will see animals ranging from very seropositive to completely seronegative with significant variability. This is what has come to be known as the subpopulation theory, where we see susceptible animals and immune animals in the same population.

Do you think there are clinical cases of circovirus on farms that vaccinate? Is this a vaccine failure or a failure in vaccination protocol?

I do not know of any case in scientific literature nor have I had any evidence of vaccine failure in the sense that the vaccine did not cover the immune spectrum to control infection. I think failures in vaccination protocol are more so related to administering the vaccine at the wrong time for that particular farm.

When something stops working that had worked in the past, it is important to make controlled changes so that we can come to sound conclusions.

If we think that problems can arise due to this variability in the breeding animals' level of immunity that I previously mentioned, we can solve this in a relatively simple manner since, fortunately, we have the tools to do so.

Each farm must evaluate its situation in order to determine the best suited program which could involve:

-

To look for a general increase in the level of immunity of the breeding sows so that breeding herd immunity is standardized in its upper range.

- By routine vaccination of replacements against PCV2 and/or

- Blanket vaccinationof the breeding animals

- Adjusting, if necessary, the age at which piglets are vaccinated.

There will be farms that maintain their same vaccination protocol and will never see a problem. We must remember that circovirus is a multifactorial disease and that the genetics, management, health status etc. of each farm, as well as the dynamics of PCV-2 itself, will affect the likelihood of observing clinical or subclinical symptoms.

How have vaccination protocols changed?

Today, vaccinating replacements as part of acclimation protocol is becoming common practice and there are many integrated companies that have already implemented this. The gilts receive a dose of vaccine as piglets and are then revaccinated as part of their acclimation plan.

Some farms have implemented the vaccination of the breeding herd, either as blanket vaccination or as routine vaccination during the reproductive cycle. The objective sought is to standarise the level of immunity in the sow herd at the upper range.

Every change in the protocol will cause the level of antibodies in the population to vary. The timing of sow vaccination will also affect the amount of immunity that will be passed on to the piglets. In some cases the age at which the piglets are vaccinated should maybe be adjusted.

Vaccinating breeding females at the end of gestation will generate very high levels of antibodies, and this also implies a very high transfer of immunity to the piglets. It is also true that PCV-2 vaccines have the potential to overcome maternal immunity, contrary to what happens in other pathologies, but this is limited, so the timing of the piglet vaccination must be balanced based on colostral immunity values.

In other situations where porcine circovirus disease is being diagnosed despite having vaccinated, the strategy used is to bump up the timing of piglet vaccination and vaccinate them earlier. We must remember that piglets are already immune in utero from 70 days of gestation, so vaccination of very young animals should not be a problem at the immunological level.

What would you say to someone who thinks they have a clinical PCV-2 problem on their farm?

The first and most basic thing is to determine that we are really facing a PCV-2 problem, and to do this we must draw on a correct diagnosis following the same system that was established over 20 years ago.

- Clinical symptoms characterized by stunted growth and wasting.

- Presence of characteristic microscopic lesions on the lymphoid organs.

- Detection of PCV-2 in lesions of lymphoid tissue.

Sending the right animals to the lab, continues to be essential for a good diagnosis. Diagnostic information provided by other tools such as quantitative PCR provides some guidance and will depend on when the samples are taken. In addition, each PCR has its own characteristics and there is no direct correlation between the PCR value and the presence of disease.

If a PCV problem is confirmed on a vaccinated farm, my recommendation would be to check the level of antibodies of the piglets at the time of vaccination, because maybe they are non-existent and vaccination should be performed much earlier, or perhaps they are extremely high and it would be advisable to delay that vaccination. This means that, on those problem farms, it would be necessary to do an individualized field investigation to determine the best vaccination protocol.

To do this, veterinarians have tools such as PCR or ELISA. Although we always say these tools are not useful to diagnose the PCV-2 disease, they are very useful for monitoring the infection. Studying the level of variability in the breeding population helps us to assess whether there are subpopulations, and implementing a strategy to homogenize the immune status of the breeding herd is recommended.

Modifying the vaccination program would involve implementing vaccination on the breeding animals and/or earlier piglet vaccination, or both strategies for a time until those vaccinated sows farrow.

Do you think we're controlling the subclinical PCV-2 infection?

That is hard to say. Perhaps the occasional cases of clinical disease that we see are just the tip of the iceberg. There may be farms that, without showing very clear clinical cases, are not benefiting from the vaccine as much as they could due to these changes in the epidemiology as we mentioned above, together with their inherent risk level based on all those multifactorial elements (genetics, husbandry, density, health status, etc.).

One thing we must remember is that when the first PCV-2 vaccines were introduced, it was a surprise, not only their effect on the clinical disease, but even more, its clear effect on the productivity of the animals due to the impact caused by the subclinical infection that we did not consider. If this improvement in the production indixes was quantified economically, perhaps we would see that it has an economic impact greater than that caused by the clinical disease.

What will be the next challenge in managing PCV-2?

Although there are still many elements to research as to how PCV-2 works, today, controlling PCV-2 is not a challenge. We have excellent tools for its control, and if we see that they do not work as they did before, we must consider why, and to do so we have techniques and knowledge.

What we could consider a challenge is knowing what changes we should make on those farms that vaccinate but have sporadic cases of porcine circovirus disease diagnosed according to the classic criteria.