In the first part of this article series we described the main three subtypes of swine influenza A virus (swIAV) circulating in swine and the introduction of the pandemic strain H1pdmN1pdm in 2009. On-farm infections by new reassortants of these subtypes and often involving multiple subtypes are being responsible for changing the clinical picture (Diaz et al. 2017), and lead to variable infection dynamics in different age groups (Pomoska-Mol et al. 2014; Ma et al. 2019). Classical epidemic outbreaks are being diagnosed less frequently. In contrast, the endemic form that is clinically recurrent is being observed in more and more farms (Simon-Grifé et al. 2015; Rose et al. 2013). The viruses on these farms generally circulate year-round. The clinical picture is often complicated by additional factors such as temperature fluctuations, other viruses (e.g. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) and/or Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2)), or bacteria (Streptococcus suis (S. suis), Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (APP), Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M.hyo) and/or Glaesserella parasuis (GPS)).

The role of influenza viruses in “paving the way” in this regard is often underestimated, however it is evident in the direct interaction with S. suis. Here, influenza viruses enable apathogenic S. suis strains to adhere within the lungs, promoting septicaemia (Lin et al. 2015) and severe course of disease. The situation is similar with GPS. Infection experiments have shown that co-infection of influenza virus and GPS, where the GPS strain used had only a low pathogenicity for itself, resulted in a more severe expression of disease (Pomorska-Mol et al. 2017). This explains why on some farms, S. suis or GPS can lead to high losses without any highly virulent strains necessarily being found. In such cases, circulating influenza viruses can often be detected in the herds.

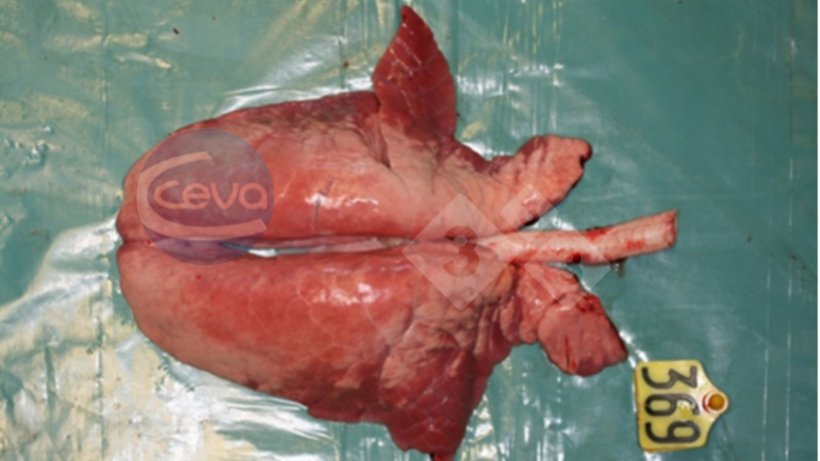

Clinically relevant signs in acute influenza outbreaks include high fever and severe respiratory symptoms, which in some cases may be associated with peracute mortality. The lung lesions found during necropsy in such cases are easily confused macroscopically with those of M hyo (Picture 1).

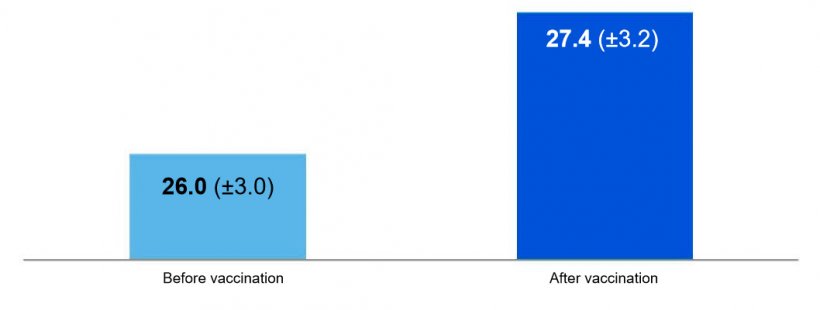

Nowadays, however, the endemic form with non-specific clinical signs is much more common and may differ depending on the production stage or type of husbandry. Grøntvedt et al. (2011) described reduced reproductive performance following the introduction of pandemic influenza viruses in several herds in Norway. An adverse influence on reproductive performance is also observed in practice, especially in the case of endemic infections with H1huN2 and pandemic strains. After experimental studies in the past could not show a negative influence of swIAV on reproductive parameters (Kwit et al. 2014; Kwit et al. 2015), a recent study (Gumbert et al., 2020) demonstrated the influence of pandemic viruses on reproductive performance in sows based on an analysis of 137 sow farms. In this study, farms where infection with pandemic influenza virus had previously been confirmed were able to significantly reduce their average return to oestrus (from 13.52% to 10.18%) following the introduction of a vaccine against H1pdmN1. In addition, one piglet more could be weaned per sow per year (Figure 1).

Aside from the effect on sows, it must be stressed that influenza poses a major challenge in terms of piglet losses in the nursery (Gebhardt et al., 2000). Based on a study in nine sow farms, in which a total of 177 weaning groups were examined for influenza it was shown that the influenza status of piglets at weaning has a significant influence on subsequent loss rates in the nursery. Mortality increased by 13% compared to the previous figure (Alvarez et al., 2015).

In fattening farms, an acute outbreak leads to classic symptoms of laboured breathing, fever (up to 42 °C) and severe coughing. The endemic form, on the other hand, is associated with increased antibiotic use to treat secondary infections, as well as reduced daily weight gains (Er et al. 2016) and possibly an increase in losses. The more severe pathogenicity of pandemic influenza viruses compared to H1N1 viruses is often seen on swine farms where the emergence of pandemic strains can be associated with severe clinical signs and high losses.

This impact of influenza on all stages of production underlines the importance of a well-applied action plan to control influenza on the farm. This includes vaccination protocols, but also the adaptation of management measures to the influenza situation on the farm.

The third part of this series is going to give deeper insights into the latest knowledge about Influenza control strategies.