It is fitting to end the calendar year with a reflection about profits since their creation is the single most important business activity of every pork producer. There may be very legitimate family goals and personal goals mixed in there too but the only business goal of the farm is not simply the creation of profits but their maximization. Profit is the societal reward for using scarce global resources in a responsible and effective way. Translated, that means when you earn a profit, you have created more real or tangible value (as society would judge it through willingness to pay), than the cost of the scarce global resources you irreversibly took from other uses to create your final product. Maximizing that behavior makes you the true and ultimate environmentalist as you seek to waste nothing (waste lowers profits and creates pollution with no offsetting value). As global resources become scarcer, failure to maximize profits in your operation will earn you an "offer you can’t refuse" from the marketplace: "Try something else as your life work".

The very fact that I have to explain that seeking profits does not originate in a criminal mindset nor land you in need of repentance, shows how far we have strayed from basic common sense and how dangerously politicized the world has become.The need to defend profit arises from the mislabeling of abject criminal activity, poor business practices like failing to pay all the costs of production and a handful of other bad management practices as "capitalism" which results in the activity of maximizing profits becoming a synonym for greed. If I steal one of your pigs so I have no cost of production and I sell it, are my proceeds called profit? Not hardly. They are called stolen money. If I work hard and smart and create lots of pork products whose value greatly exceeds the cost of the resources used to create them shall I be called greedy? No, profitable. Simple, isn’t it? You will probably need to remember that in the coming year.

In the language of economics, pork production (as well as all commodity production) is often referred to as a "margin" industry. By this, we mean that over time (not necessarily today, this month or even this year), the market will pay, on average, the fair cost of producing pork (no more and no less). Of course, governments, subsidies, externalities etc. can thwart that but absent some persistent interference from outside the marketplace, the long run average profit of pork production is the fair return to the resources used and the risk of organizing them to produce these products. Therefore, when we see periods of very high profits or very deep losses, we know that market forces will tend to grind away to turn the extremes back toward the long-term average. With a well-capitalized and well-run farm, this is encouragement during times of losses as we know an end will come before we are forced out. The not-so-well-capitalized or well-run farms will exit first (or reduce their production or market weights) and this mechanism will bring back positive returns. The same goes for periods of high profits, such as those anticipated in the coming months. Lots of forces will spring into action to limit the duration of high profits and return things toward "normal". Those things include increasing market weights, expansion of production, sloppy production practices that seem to creep in when profits get high, increased demand (and therefore cost) of inputs such as feed ingredients but also building supplies and services and don’t discount increases in exports of cheap feed ingredients making them more scarce for domestic users.

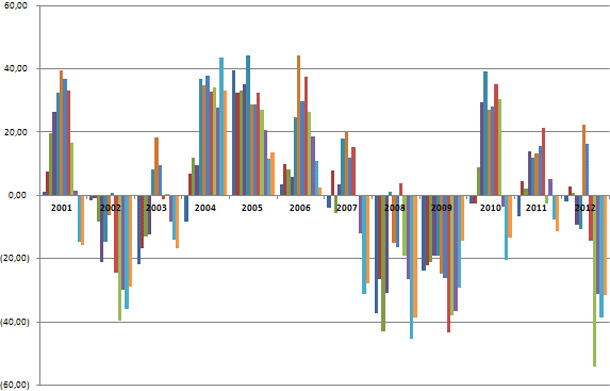

If you take a look at Figure 1, you will see the annual monthly estimated returns to produce a 270lb (123kg) finished pig from 2001 through the drought year 2012. These are estimated from formulas not actual returns of any group of producers. This data series is the work of John Lawrence and Shane Ellis at Iowa State University (you can find the assumptions here). While it may not perfectly represent your costs and returns, it probably illustrates their direction and magnitude closely enough to make my point. Note how the market constantly corrects over time, cycling between profits and losses.

Figure 1. Monthly estimated returns to farrow-to-finish production of a 123 kg liveweight hog

Lawrence and Ellis, Iowa State University

www.econ.iastate.edu/estimated-returns

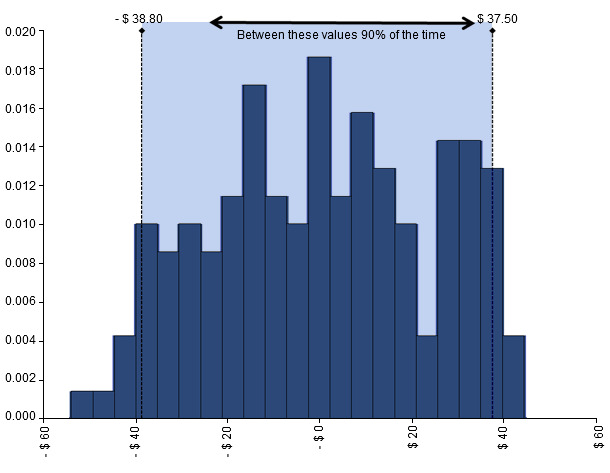

Since we have been working with distributions, Figure 2 depicts the probability distribution of these same estimated returns over the same period. You should note returns are bounded by losses and profit per head in the upper $30 range. Only five percent of the time does this series fall below or go above that range. This is the meaning of a margin business. Forces tend to restore it to a long run equilibrium which serves up a fair return or profit. Remember that this fair return is for the average producer and in the case of these estimates the long run average is almost zero in the period shown. This is probably because of the unusual drought in 2012. In 2014 if you focus on the worthy goal of profit maximization, you can hopefully be one of those producers in the right hand tail of the distribution of net returns that is making higher than industry average profits all of the time. Remember as you get ready for next year, it’s a worthy goal, not only for you but for society too.

Figure 2. Estimated net returns 2001-2012 farrow to finish 270 lb live weight pig

Lawrence and Ellis, Iowa State University

www.econ.iastate.edu/estimated-returns