In May 2017, the laboratory was contacted for a case of massive sudden mortality at three different commercial pig herds, spread in Flanders, Belgium. In one case, mortality occurred in the weaned pigs, the other herd had problems with the lactating sows and the third herd had massive mortality in the growing pigs in five different compartments. None of the herds was connected to each other in either way (not the same breeder, feeding company, veterinarian, …). Necropsy revealed in all 3 cases: nitrite intoxication.

This case report describes the latter case of mortality: massive sudden death in fattening pigs.

Anamnesis

March, a Monday morning, 8 am. The herd veterinarian was called by the farmer of a fattening herd: 30 pigs were dead in different compartments in the stable, and while speaking some more suffered from acute mortality. At 11 am, yet more than 50 pigs of different ages and in different stables died without any clinical symptoms.

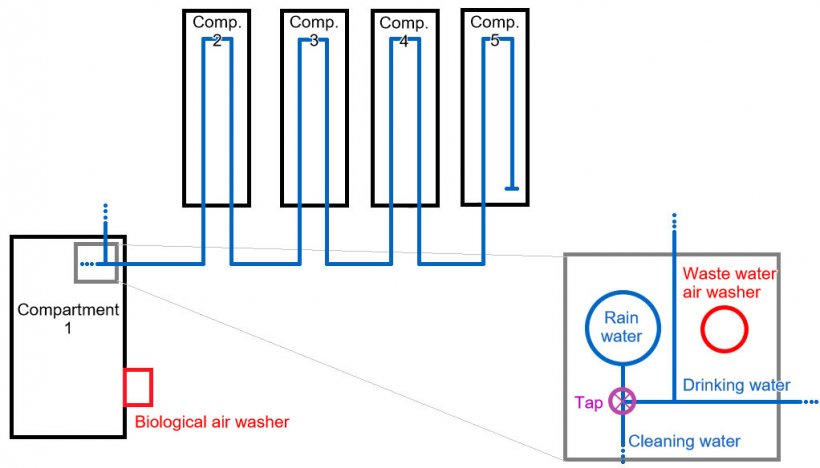

Piglets arrived at the herd at about 20kg (12 weeks of age). The herd had a capacity of 2500 growing pigs and consisted of 5 compartments (500 pigs each): one new compartment, where the youngest pigs are housed and four older stables (figure 1).

Drinking water is provided from a bore pit, and is regularly analysed as well for chemical composition as a bacterial analysis, in order to only provide drinking water of good quality to the pigs. Pigs are fed with a commercial feed for growing pigs.

Rain water is only used for cleaning the stables.

The herd uses a biological air washer, in order to reduce odour and gaseous emissions from the pig herd (figure 2).

Observations at the herd visit (Monday afternoon)

The first image when arriving at the herd, was a stack of dead pigs lying in front of the stable (figure 3). The farmer went in and out compartment 2 with a wheelbarrow filled with dead pigs…

Walking through compartment 2, several clinical symptoms were noticed: some pigs were vomiting, others showed nervous signs such as paralysis and lateral recumbency. Other pigs died immediately. Death occurred in a few minutes.

Highest mortality numbers were recorded in compartment 2 (>50%) and 3 (20%), less in compartment 4 (10%) and none in compartment 1 and 5. Worth to mention is the start of the drinking water pipe line system which is located in compartment 2.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for sudden death in growing pigs is as follows:

- Infectious causes: Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Actinobacillus suis, Lawsonia intracellularis, diseases causing septicemia: Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Salmonella choleraesuis, …, Aujeszky’s disease (Belgium is officially free), CSF (Belgium is officially free), Brucellosis (Belgium is officially free), …

- Noninfectious causes: bleedings (eg. Stomach ulcers), twisted gut or mesenterial torsions, hemorrhagic bowel syndrome, electrocution, trauma, stress, intoxications (cyanide, urea, pesticides, toxic gases (eg. carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide), chlorates, aniline dyes, aminophenols, or drugs (eg. sulfonamides, phenacetin, and acetaminophen)), mycotoxins and grain overload, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, pulmonary adenomatosis or emphysema, aneurysms, …

Diagnostics

Necropsy at the herd itself, revealed a dark discoloration of the blood. Mucous membranes showed dark red discoloration close to becoming cyanotic (figure 4).

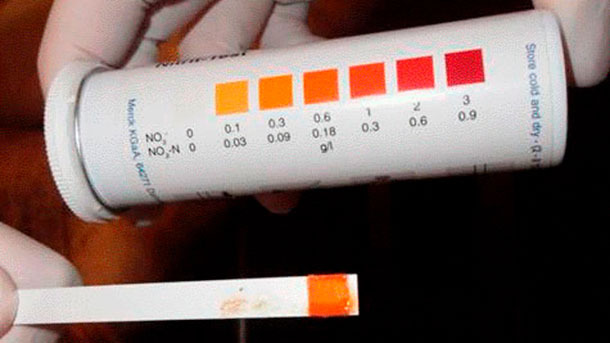

Six pigs were transported to the laboratory in order to perform a full necropsy, including testing with a stick with nitrite test field (figure 5).

These were the abnormalities found (figures 6):

- 6 pigs: 2x 34kg; 2x 37kg; 67kg; 89kg

- 6x pale muscles; 6x chocolate brown discoloration of the blood; 6x positive nitrite test

- 5x spumous liquid in trachea, 6x hemorrhagic and oedematous lungs (no pneumonia), 2x multiple bleedings spread in the lung parenchym

- 1x spotted bleeding in heart coronaries.

- 1x splenomegaly (figure 7)

First approach

Due to the massive mortality in all compartments, with the majority in compartment 2, at the beginning of the drinking water distribution system, and due to the quite clear diagnostic feature of dark discoloration of the blood, the presumable diagnosis was nitrite intoxication. The first and immediate advice given was to shut down the drinking water.

Mortality stabilized, which confirmed the suspicion of the drinking water being the source of nitrite.

A truck with a tank filled with clean city water was asked to provide the pigs of drinking water.

The reservoir of the drinking water was emptied, cleaned and then filled with the clean water.

The moment pigs started drinking again, mortality started all over again… Pipe lines were immediately closed again and the surviving pigs were provided with drinking water in buckets by hand.

As the drinking water was the main suspect of the source of nitrite, samples of the drinking water were taken and sent to the laboratory for analyses. Results are shown in table 1. The first three samples were taken by the herd veterinarian in the morning, the two subsequent samples were taken during the herd visit in the afternoon. None of the samples revealed a too high concentration of nitrate neither of nitrite.

The challenge was to investigate the origin of the nitrite poisoning. It was quite clear that the drinking water was the source, however, analyses did not confirm this.

Tuesday morning a technician came to the herd and discovered the problem:

Waste water of the biological air washer was stored in a reservoir located next to the reservoir of the rain water. The reservoir had not been emptied during winter, was completely full and flew over into the reservoir of the rain water. Thus, rain water was contaminated with waste water, which contains a high concentrations of nitrate. In normal circumstances, rain water was not used to provide pigs of drinking water. However, there was a connection between the rain water pipes (which are used for cleaning) and the drinking water pipes, normally closed by a tap. By mistake, the tap had been opened in the weekend. Another malfortune was a malfunction in the water pump, causing the drinking water for the pigs not being drawn from the regular circuit, but from the contaminated rain water.

As the analysed samples did not come from the rain water, no contamination could be demonstrated. After discovering this huge mistake, samples of the rain water were taken for analysis. The results can be found in table 2. No high amount of nitrite was found, but the nitrate levels were excessively high.

Discussion

Nitrite intoxications in pigs are mostly the result of oral uptake of contaminated drinking water (Vyt et al., 2005). Also in this case the drinking water was the source. Two other cases in the same period in Flanders had also drinking water as the source of nitrite ingestion. However, in the first case weaned piglets arrived in a fattening barn, which had been empty for several weeks. Standstill of the drinking water in the reservoir and water distribution system and pollution of decaying organic material, with subsequent nitrite formation due to bacterial reduction of nitrate was the origin of the contamination. This is a frequent cause of nitrite ingestion (Vyt et al., 2005). Pipelines were not cleaned before the pigs entered nor were they washed through. Piglets died in a few minutes, even while the last piglets were still on the truck. Closing the drinking water pipeline prevented 100% mortality. Only 15 piglets died.

In the second case, contamination of the drinking water was comparable to the case described here. The reservoir of the waste water of the biological air cleaner, flew over in the drinking water tank, causing acute mortality in the lactating sows – as the farrowing unit was the first compartment of the drinking water circulation system. Thanks to the alertness of the herd veterinarian, the pipelines were immediately shut down, whereby only 40 sows died.

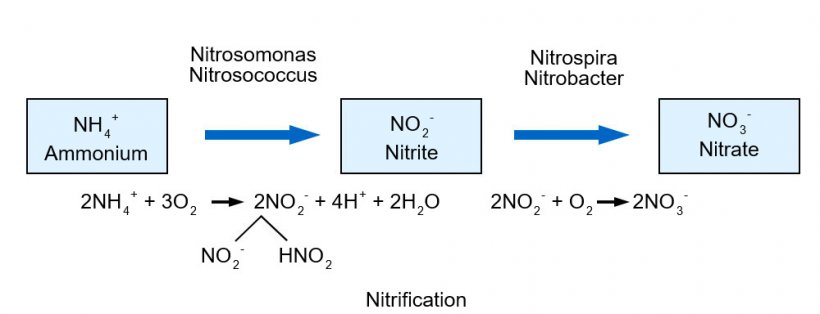

Biofilters are a proven and effective method for reducing odour and other gaseous emissions from mechanically ventilated animal facilities. The principle of biological air cleaning is that bacteria process the unwanted particles out of the air, such as the ammonia. Subsequently a nitrification process is started.

The waste water of biological air filters contains thus high amounts of nitrite and nitrate.

Although all clinical symptoms in this case pointed towards a nitrite intoxication, diagnosis could only be confirmed with the nitrite test sticks at necropsy. The exact level of nitrite or nitrate in the stomach has not been determined in this case. Also the drinking water was analysed, as the possible source of the poisoning. No high levels of nitrite could be found in the drinking water, only nitrate was present.

Transformation to nitrite after ingestion is mediated by gastro-intestinal bacteria (Duncan et al., 1995). Ingestion of nitrate by pigs is known to have no adverse effects at a concentration up to 2000 mg/l (Sorensen et al., 1994). In this case nitrate levels were much higher than 2000 mg/l at the reservoir. It is uncertain how high levels were at the moment of drinking by the pigs, as the first samples, taken in the morning after the first detection of dead pigs, at the drinking nipple in compartment 2 showed no high levels neither of nitrate nor nitrite. However, in this case, it seems that ingestion of high amounts of nitrate was sufficient to cause the problems.

Treatment with methylene blue has not been used in this case. A rapid removal of the nitrite source is essential to prevent further mortality. As the precise source of contamination was not immediately found in the present case, pigs were exposed twice to the toxic water. In total 757 (or 25% of the total number of animals) pigs died.

Conclusion

In conclusion, anno 2017 nitrite poisoning does still occur in modern pig facilities, even more with the presence of the biological air treatment. Therefore, nitrate and nitrite intoxication should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis when facing problems with acute mortality in pigs!

More on intoxication by nitrate or nitrite ingestionMethaemoglobinaemia, caused by nitrate or nitrite ingestion (Buck et al., 1976; Fan and Steinberg, 1996) can sporadically cause sudden death in pigs (Vyt and Spruytte, 2006). Nitrite is a toxic gas, formed by nitrate, which is commonly found in plants, fertilizers and animal wastes or decaying organic matter (Buck et al., 1976). Nitrite is readily absorbed into the circulatory system and scavenged by the erythrocytes after ingestion (Vyt et al., 2005). When nitrite oxidizes the Fe2+ ion within the hemoglobin molecule into Fe3+, methemoglobin is formed, causing an inhibition of the oxygen binding capacity of the erythrocytes (Wendt, 1985). Symptoms, caused by nitrite intoxication, are correlated with the percentage of methemoglobin formation and the resulting degree of tissue anoxia. They range from a marked increase in respiratory rate, restlessness to dyspnea, animals showing a staggering gait, general weakness to coma and death – acute mortality occurs when methemoglobin concentrations are higher than 75% (Wendt, 1985; Saito et al., 2000). Methaemoglobinaemia can manifest itself in brown discoloration of the blood (Vyt et al., 2005), which can be seen on post-mortem examination, mostly combined with pale muscles. The conjunctivae and mucous membranes become cyanotic. During necropsy, diagnosis can be made by wrubbing a strip inside the stomach, containing a nitrite test field figure 5). The only treatment for nitrite intoxication is administering methylene blue intravenously (10mg/kg), which brings a reduction of the methemoglobin to hemoglobin (Wendt, 1985). However this is almost never done in practice in Belgium. |