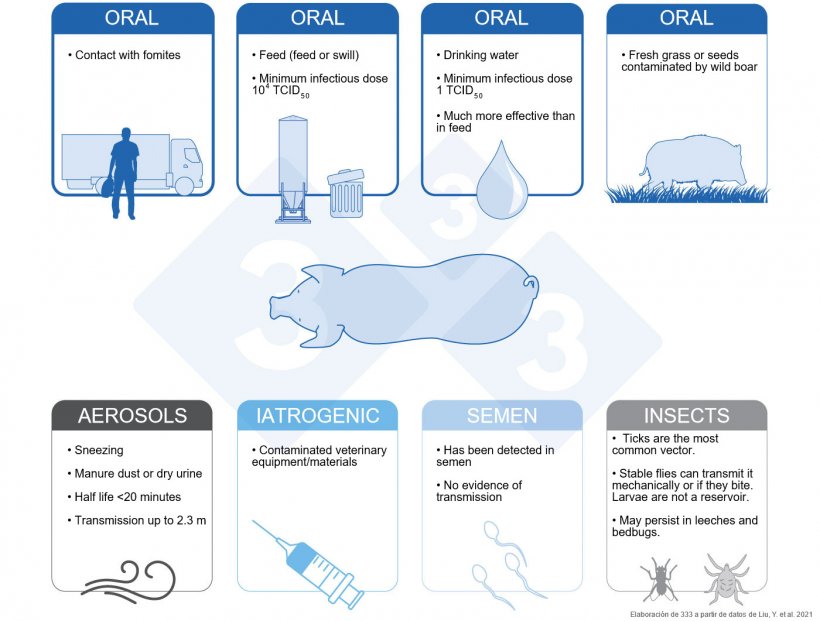

1. Oral transmission

The most important transmission routes of African swine fever virus (ASFV) are oral transmission routes, mainly via ingestion of feed and/or contact with fomites/objects contaminated with viral particles. The persistent viability of the virus, as well as difficulty inactivating the virus (Table 1) contribute to making it difficult to control.

Pigs that ingested feed contaminated with the Georgia 2007/1 strain were infected with a minimum infective dose of 104 TCID50 with a median of 106.8 TCID50. In the same study, the minimum infective dose of ASFV in drinking water was just 1 TCID50 with a median of 10 TCID50, indicating that transmission of ASFV through drinking water is much more efficient than through feed (Niederwerder et al. 2019).

Historically, ingestion of human food scraps or swill has been shown to be an important pathway for the spread of ASFV.

Fresh grass and seeds contaminated by infected wild boar are potential sources of infection for backyard pigs (Guinat et al. 2016).

Table 1. Viability of ASFV under different conditions (Source: Liu, Y. et al. 2021).

| Parameter | Viability | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 37ºC – 11-21 days |

Mazur-Panasiuk et al. 2019 Juszkiewicz et al. 2019 |

| 56ºC – 60 -70 minutes | ||

| 60ºC – 15-20 minutes | ||

| Blood | Stored at 4ºC – 18 months | Beltrán-Alcrudo et al. 2017 |

| Putrefied blood – 15 days | ||

|

Slurry |

Feces at 4ºC – 8 days |

Davies et al. 2017 |

| Feces at 37ºC – 3-4 days | ||

| Urine at 4ºC – 15 days | ||

| Urine at 21ºC – 5 days | ||

| Urine at 37 ºC – 2-3 days | ||

| Pork | Pork at 4-8ºC – 84-155 days |

Mazur-Panasiuk et al. 2019 Beltrán-Alcrudo et al. 2017 |

| Salted pork: 182 days | ||

| Dried: 300 days | ||

|

Cooked pork (minimum 30 minutes at 70ºC): 0 days |

||

| Smoked pork: 30 days | ||

| Frozen pork: 1000 days | ||

| Refrigerated pork: 100 days | ||

| Water | At room temperature: 50 days |

Sindryakova et al. 2016 Mazur-Panasiuk et al. 2019 |

| Feed | At room temperature: 1 day |

2. Aerosol transmission

ASF-infected pigs shed virus into the environment through excretions and secretions, and the viral load in oral fluid, nasal fluid, feces, and urine is particularly high during the acute phase (MacLachlan et al. 2017). When pigs exhibit respiratory symptoms such as sneezing and/or coughing, these secretions can become virus-carrying aerosols. When virus-contaminated feces or urine dries, dust caused by animal movement can also generate virus-carrying aerosols (De Carvalho Ferreira et al. 2013).

The half-life of ASFV in the air is 19.2 minutes (qPCR test) and can be transmitted over a distance of up to 2.3 meters between infected and susceptible pigs.

In conclusion, ASFV can be transmitted within the farm in the form of aerosols, which could be an important mode of ASFV transmission on swine farms.

3. Iatrogenic transmission

ASFV can spread from infected pigs to susceptible pigs via contaminated veterinary equipment/materials, such as needles used for vaccination (Penrith et al. 2009 & Beltran-Alcrudo et al. 2017). However, the efficiency of iatrogenic infection and its importance in the epidemiology of ASFV remain unclear.

4. Transmisison via semen

Although there is no direct evidence that ASFV is transmitted through semen (Mazur-Panasiuk et al. 2019), there are studies showing that ASFV can be detected in semen from infected boars (Thacker et al. 1984).

5. Transmission via insects

ASFV can replicate in ticks (Ornithodoros spp), and they are the most common vector of the virus (Mazur-Panasiuk et al. 2019). These ticks live in wild boar nests, and adults can live for decades and survive for a long time without eating, making Ornithodoros ticks an ideal reservoir for the virus. Other insects can also spread ASFV. The stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) can transmit the virus mechanically to susceptible pigs (Mellor et al. 1987) and can also transmit it by biting. At this time, the role of flies in the epidemiology and transmission of ASF is not entirely clear. Fly larvae are not a reservoir for ASF and cannot mechanically spread the virus (Forth et al. 2018). Recent studies have shown that ASF could persist in leeches (Hirudo medicinalis) and bedbugs (Family: Reduviidae, Subfamily: Triatominae) (Karalyan et al. 2019 & Golnar et al. 2019).

Liu, Y., Zhang, X., Qi, W., Yang, Y., Liu, Z., An, T., Wu, X., & Chen, J. (2021). Prevention and Control Strategies of African Swine Fever and Progress on Pig Farm Repopulation in China. Viruses, 13(12), 2552.

333 Staff