The swine industry is facing increasing challenges, being health control one of the most significant which is currently under increasing pressure to reduce and limit antibiotic use. This scenario makes biosecurity a first-level disease prevention tool (Wood et al., 2011).

In this context, it seems that all roads lead to biosecurity, and according to the latest studies, it appears the best way to approach biosecurity is not the same in all cases. Buccini et al. (2023) describe how advances in biosecurity are established according to people's perception and tolerance of risk. Thus, we find two contrasting realities; one associated with situations classified as high risk, where decisions must be made quickly and strictly, and the other where the perceived risk is lower and responses are more gradual and less effective.

In short, to be efficient in biosecurity and protect our farms, it is not enough just to be technically competent; we must also know the environment in which we apply it and understand the people in charge of implementing the proposed measures.

In this line, the survey published by Pig333 following the biosecurity webinar last October revealed some interesting points regarding the opinions of the industry professionals who completed the survey. It included over 400 responses from several countries.

The questions posed and the responses obtained were as follows:

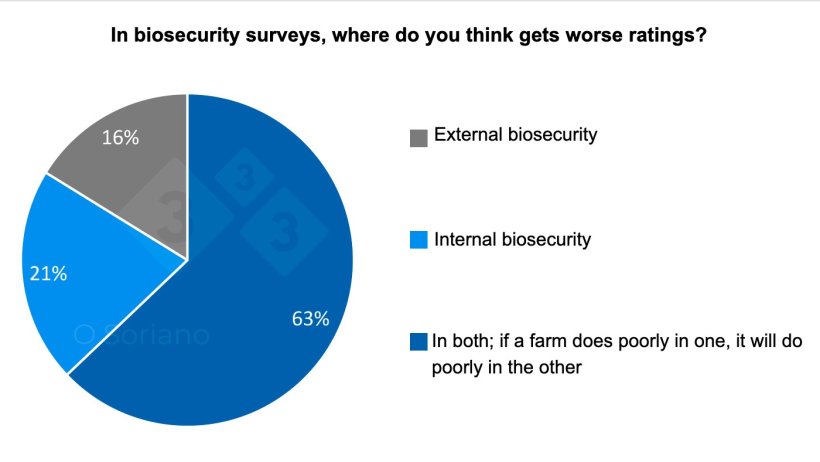

Graph 1. Distribution showing where respondents think worse ratings on biosecurity surveys are received.

The majority response was in both (62.9%), with respondents considering biosecurity failures to be generalized, affecting internal and external biosecurity equally. Internal biosecurity failures came in a distant second place.

The Biochek.Ugent database has 54,339 surveys conducted to evaluate biosecurity on pig farms. According to the database, internal biosecurity is generally rated worse on both sow and finishing farms, with averages of 76% and 69% respectively (February 2024), as shown in graphs 2-5 (Biocheck.UGent in Project Prohealth EU).

Graphs 2 and 3. External and internal biosecurity scores for sow farms (76.3 and 56.9 out of 100, respectively).

Graphs 4-5. External and internal biosecurity scores for finishing farms (67.4 and 59.2 out of 100, respectively).

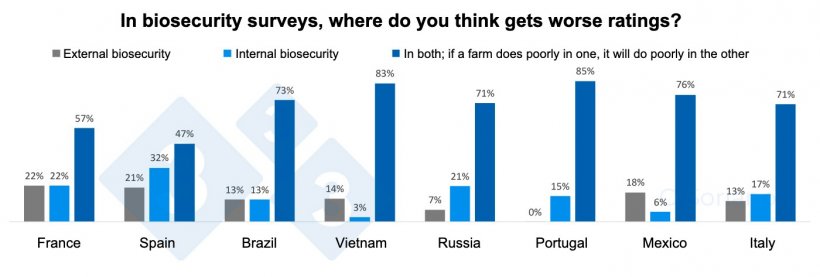

Graph 6. Perception of external and internal biosecurity by countries.

Regarding the responses by profession, it is interesting that a higher percentage of researchers correctly indicate that internal biosecurity gets worse ratings. Graph 7. Distribution of responses to the best strategy for implementing a biosecurity plan.

The most common response (51.0%) was "Implement as quickly as possible and with strict measures" although "Implement slowly" followed close behind (41.3%). According to the latest studies on biosecurity behavior (Buccini et al.) the first one is correct in high-risk situations and coincides with what the survey shows us, with higher scores in countries strongly threatened by ASF, such as Vietnam and Russia. This response can be associated with the perception of that serious threat. A more gradual implementation of biosecurity protocols could be considered only in situations with a high health status and therefore a lower perceived risk (i.e., countries with a high general sanitary status such as Brazil or Argentina).

Graph 8. Distribution of responses to the best strategy for implementing a biosecurity plan according to country.

Regarding opinions based on the role of the respondent, the range of opinions is narrow between different professions. We observe that farmers mostly prefer to propose quick and strict interventions (56.48%) and agronomists mostly prefer gradual interventions (48.83%).

Graph 9. Distribution of responses to the best strategy for implementing a biosecurity plan according to the respondent's role.

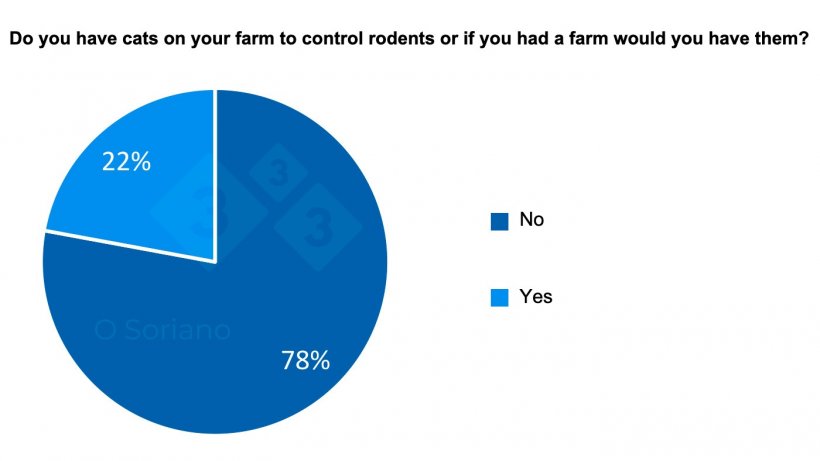

Having cats for rodent control is mostly rejected (77.90%), although it seems there is great room for improvement since 22.1% of those surveyed think it is good to have them. There are two countries far ahead in avoiding having cats (Vietnam and Russia, 89.18% and 93.33% respectively), perhaps also related to the perception of the threat of ASF. Regarding the associated professions, students and veterinarians show the highest rate of rejection (93.75% and 83.90%, respectively).

Graph 10. Distribution of responses to whether respondents have or would have cats on the farm.

Conclusions

The results of this survey reveal that although the perception of biosecurity and its implementation is generally in the right direction, there is still a lot of room for improvement among many professionals in the industry who are not fully aware that internal biosecurity is often rated worse than the external, and neither are about the advantages of quick and strict application of biosecurity protocols in high-risk situations, or the risks of having cats for rodent control.

All of this should motivate us to improve the information offered on our farms with well-structured and internationally standardized surveys such as Biocheck.UGent. Additionally, through the ADA Biocheck more detailed studies can be carried out on the factors that affect biosecurity not only on individual farms but also on groups of farms or companies, promoting more specific corrective and training actions for farm personnel, veterinarians, consultants, or researchers always seeking to improve biosecurity, always considering it as a 24/7 job.