We come to the close of a year filled with (mostly) happy surprises in both the US and EU hog industries. Much of the story is export-related and the good news, as we mentioned last time, is that it is expected to continue through much of 2018. The US Meat Export Federation reports that the latest monthly US pork export numbers (September) have slowed some from their blistering pace of up to eight percent ahead of last year’s record total during the first three quarters of the year, both the value and the tonnage are up and taking just shy of 25% of total US hog production out of the country.

I am aware of the old saying, “If you must forecast, you must forecast often”, which should humble anyone who sticks their neck out too far with predictions. However, several large banks and investments houses this month in the US have joined the forecast of the World Bank that 2018 will be a year of continued growth in income for most nations throughout the world. The only places left out will be countries where government corruption is especially high. Higher incomes bring more demand for pork.

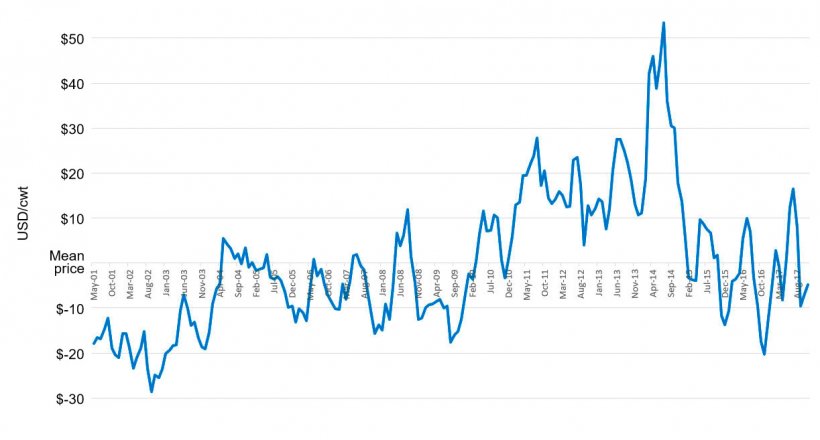

Hog prices in the United States returned to an incredibly stable, base price level that we have pointed out previously. This (unadjusted) price level has been in place since about 2004, only deviating for two significant events. First, when commodity (feed ingredient prices) sky-rocketed at the financial collapse of 2008 on through a peak caused by the devastating drought of 2012. The second temporary break in the pattern occurred when the disease PEDv destroyed over 10% of the US pig crop in 2014. The industry quickly recovered however and the previously established trendlines of both productivity and productivity growth were quickly reestablished.

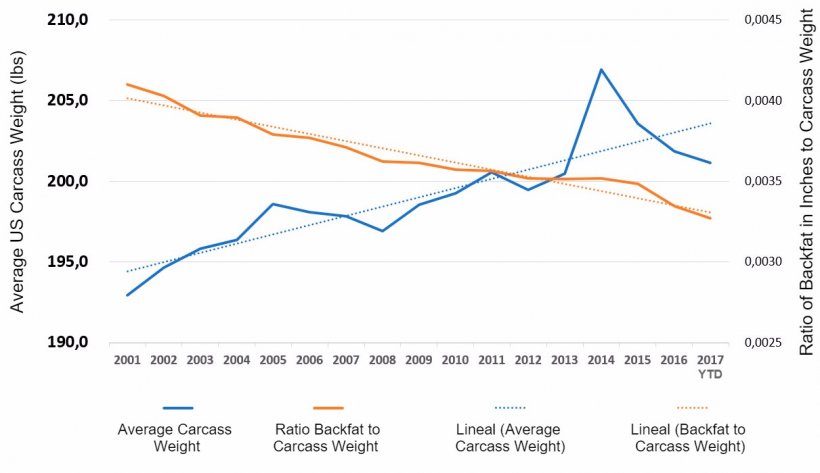

The normal seasonal patterns move around this long-established base price level, however, there is very little long-term trend in this base price for over fifteen years. This coincides with the almost imperceptible inflation in the US general economy (post 2008 financial collapse) despite extended years of stimulus and near zero interest rates. For that relatively flat price, however, the US industry has delivered steadily more total carcasses as well as a steadily heavier carcass.

A look at USDA statistics reveals those steadily heavier carcasses also have an increasing lean percent. In addition, even though loin area and loin depth generally increase with carcass weight, a ratio of these values to the carcass weight reveals an upward trend demonstrating increasing genetic progress delivering more value at the same long-term price. There are many drivers of these trends but none of them are possible without profitability. Since the drought of 2012 ended, this has been largely delivered by an incredibly steady harvest of very large US corn and soybean crops (this year is no exception) providing a very stable and profit-enabling price for feed ingredients. Couple that with a revenue side created by the temporary shortfall of pigs due to PEDv and steadily increasing domestic and net export demand and you really have a rare mix of coincidently positive profit enablers. For many producers, 2016 was a near breakeven year due to the unusually poor fourth quarter results but 2017 has produced both record production and the strongest net returns since the PEDv induced shortages with the fourth quarter surprisingly approaching near breakeven on average for many producers.

The US industry has exhibited a very disciplined and significant increase in slaughter capacity this year which has been driven this time by long-term future sales deals (as well as forecasts) coupled with coordinated supply increases dedicated to and organized to be ready for the plant opening periods. This is in distinct contrast to “If we build it they will come” bravado which typically causes a devastating showdown characterized by price wars, below breakeven operation to drive competitors out and equity losses for nearly everyone. Since the larger plants opened in September, the US industry has steadily broken and rebroken record total weekly harvest numbers throughout the fall.

The US is increasingly moving toward a much more coordinated industry with respect to production and processing. Some of it is integrated but the newly successful coordinated models are large production companies owning or co-owning large, modern processing plants and therefore having transparency of information flow, the ability for staging and planning production levels well in advance as well as moving the locus of chain-wide profitability more and more to the production companies.