Next to the introduction of infected swine (i.e. pig-to-pig transmission), introducing disease via organisms on fomites (i.e. cross contamination) is considered one of the top risks for disease transmission into a farm. Vehicles that transport animals (i.e. live and dead), feed, service people, and supplies often need to travel between swine facilities. Without question, vehicles are, quite obviously, the largest and sometimes the dirtiest fomites. When there is no decontamination after high risk events like: swine facilities of low health status, dead stock handling locations and slaughter plants, the risk of disease contamination around your swine facility can increase dramatically. Although the industry is making significant investment in better cleaning and disinfection systems for vehicles (e.g. TADD or Thermo Assisted Drying and Decontamination of animal’s transport vehicles), it can be challenging to ensure the disease-free status of all vehicles that enter our farm sites. Analysing and modifying traffic patterns can have a significant impact by minimizing disease transmission risks associated with vehicle movements.

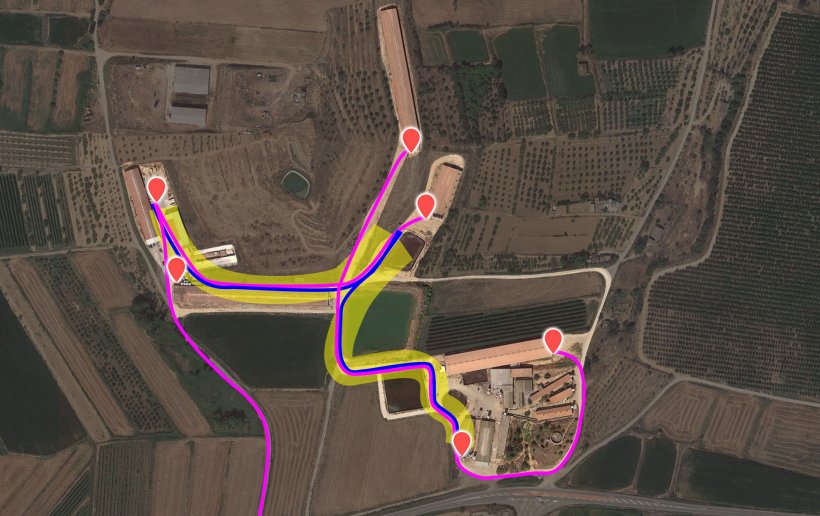

In this article, we will review a real-life example of how one swine production system in the northeastern region of Spain performed a vehicle traffic analysis which guided the implementation of modifications to traffic flow and other biosecurity upgrades that will protect the farm from new disease introductions. Understanding this process will help producers and veterinarians to identify and focus on eliminating or managing traffic areas of higher risk for each site that is under the microscope. In this article, we use a practical example of a commercial farrow-to-finish farm system that is located on one premises (Picture 1). Pigs are transferred between the three segregated stages of production (i.e. breed to wean, nursery, and finisher). The site uses both onsite dedicated and external third-party vehicles for animal movements.

On the first visit of the vehicle traffic biosecurity assessment we analyzed the farm using a satellite image. We focused our conversation on understanding the next following points:

- Farm layout (i.e. Production stage of each building; feed silo locations; supply entry points; personnel entry/exit points, animal entry/exit points) (Picture 2; You can zoom on the images by clicking on them);

- Vehicle flow patterns (i.e. worker/visitor vehicles, third party external and internal farm owned vehicles used for animal movements, feed deliveries, supply vehicles, service vehicles, etc). For the purposes of this article, we will limit our review to animal movement vehicles (Picture 3);

- Loading chute design and usage (i.e.: load-in, load-out or both types of movements in the same location).

As shown in Picture 1, we quickly observed that the external and internal animal movement vehicles had overlapping traffic patterns and were also using the same loading chutes. The areas that represent a higher risk for cross contamination between external and internal vehicles are highlighted in yellow. Typically, from the biosecurity perspective, we should consider 2 types of loading chutes. Their usage is based on type of animals being loaded and cleanliness status of vehicles. They can be categorized as follows:

- Internal flow loading chute: Dedicated to the load-in and the load-out of animals (i.e. farrowing to nursery, nursery to finisher, internally produced replacement gilts to adaptation facilities) or incoming high health replacements (being transferred into the farm) and only contacted by internal farm vehicles that are not used off of the farm.

- External flow loading chute: Located in a separate location from the previous chute to avoid cross contamination with internal movements. Dedicated to loading out market and cull animals and only contacted by externally owned transport vehicles.

Based on the traffic pattern analysis and the identified areas of cross contamination between vehicles and people, a new traffic flow patter was designed and proposed to the producer. As well, a very important biosecurity upgrade that was suggested. Building a set of 4 new loading chutes to clearly separate the internal and external vehicle routes (Pictures 4 and 5).

In the case of this farm, no new openings were required to create these new loading chutes, and this reduced the cost of implementing the recommendations. The solution included a set of platforms (Picture 4) that used gates to direct the pigs flow to the old chute (for internal flow use) or the new chutes (for external flow use). This platform helped to create a spatial separation between the routes of transport and effectively lowered the risk of cross contamination.

Other important changes that were recommended involved the addition of fencing and gates that would prevent the incorrect use of different roads within and around the farm. Although cross contamination risk was lowered (Picture 7), some fencing could not totally restrict the movement between the clean and dirty zones. Finally, as a result of the new farm fencing, some silos were moved closer to the fence so that feed trucks would not enter inside the perimeter of the farm zone.

As mentioned earlier in the article, this discussion only reviewed the animal movement analysis and upgrades. A full traffic analysis was completed, and recommendations were also made for personnel, supply, and service movements.