What is antimicrobial resistance, why and how does it happen?

Resistance to antibiotics is the phenomenon by which bacteria are not affected by the lethal or inhibitory action of an antimicrobial molecule. This process has been happening regularly in nature for thousands of years: antibiotics are produced by bacteria and fungi in nature with the aim to eliminate competition in a particular ecological niche.

Bacteria that come in contact with these antibiotics develop mechanisms to resist them, enabling them to colonize places with nutrients and few competitors.

Most of the antibiotics used in both human and veterinary medicine have their origin in nature from these compounds and it is just a matter of time that the clinical use of antibiotics allows these very efficient resistance mechanisms generated by nature to be selected.

Is resistance to antibiotics transferred between different types of bacteria?

Yes, and that is one of the major problems. In general, bacteria have three ways to resist the effect of antibiotics: changes in the antibiotic target, destruction of the antibiotic or expulsion of the antibiotic to the outside. In general, these resistance mechanisms can be transmitted both vertically and horizontally, which means, they can be transferred both to the following generations and to other bacteria of the same or different species.

Can the same bacteria be resistant to several antibiotics?

Bacteria are able to accumulate resistance mechanisms to several antibiotics. This happens mainly in places with high antibiotic pressure such as hospitals or, to some extent, livestock farms. In these environments, bacteria must evolve to survive, so they adapt and acquire resistance genes from their environment. An example of this are, in farms, bacteria from the environment or bacteria present in the microbiota of the animals that may have been recently introduced in the herds.

Are resistance genes ubiquitous?

No doubt. As it is a natural defence mechanism against natural antimicrobial molecules, resistance genes are found in all ecological niches. Besides, the spread of resistance genes is a global problem, because the use of antibiotics, or their presence in the environment, has produced a positive selection on the bacteria with these genes. In today’s world, where a person, animal, food or material can easily go from a place to another thousands of miles away in a matter of a few hours, it is not unrealistic to think, and it is has even been proved, that resistance genes spread just as easily. It is also true that the levels of resistance are higher in some countries and this is due, amongst other things, to their national plans to control antimicrobial resistance.

How can antimicrobial resistance be measured/valued?

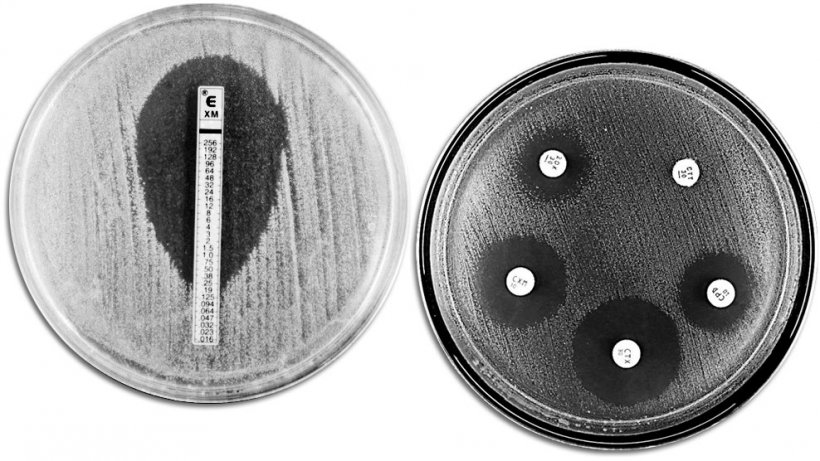

The levels of antimicrobial resistance can be measured using several techniques. Classical techniques, such as antimicrobial diffusion tests and the microdilution method, allow us, once the causative pathogen has been isolated, to determine the antibiotics to which it is resistant or sensitive, and to know its resistance levels. These techniques, widely used in human medicine, should be largely implemented in the veterinary field, as they have a high cost/benefit ratio.

On the other hand, the modern molecular biology techniques enable us to know the levels of resistance in broader horizons. Nowadays, our lab is part of the most important European veterinary medicine project to fight antibiotic resistance in the food chain, called EFFORT (Ecology from Farm to Fork Of microbial drug Resistance and Transmission). This project is being carried out in a harmonized manner in 10 countries of the European Union, where samples have been taken at all levels, from animal production (pigs, poultry, turkeys, trouts, and beef cattle) to slaughterhouses and retailers. Thanks to this project, we will be able to know the antimicrobial resistance level in Europe from farm to table.

Classical techniques for evaluating antibiotic resistance. The picture shows an E-TEST on the left-hand side to measure the minimum concentration of antibiotic that prevents bacterial growth. The right-hand side shows an antimicrobial susceptibility test with different growth inhibition zones produced by the antibiotics.