In line with recent articles on data analysis as a basic tool for the improvement of production, we present the results of a recent published study that predicts the sows' performance based on the results obtained in their first farrowing (Ilida, Pineiro and Koketsu, 2015).

The study is based on a total of 715,939 services, 476,816 farrowings and 109,373 lifetime records of sows spread over 125 farms in Spain, Portugal and Italy, which started their productive lives in their respective farms between 2008 and 2010. It is worth noting that the study conditions, including farms with different genetics, size, health status, structure and management, will enable the extrapolation of its findings to all farming conditions.

The study evaluates several effects, such as predicting the sows' future production based on their first farrowing results, or the relationship between the optimal age at first service and the time of year, something all professionals suspected existed, but has never been precisely determined. However, the most innovative outcome of the study is the characterization of an existing elite sub-population in the farms made up of those sows —known as gifted sows or super-sows— that will always perform better than their peers.

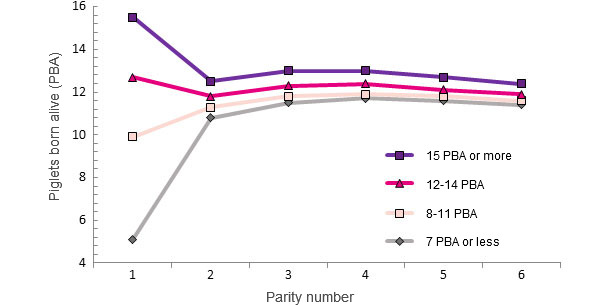

Among the different variables the study was based on, the most decisive one to explain the sow's subsequent performance turned out to be the number of piglets born alive (PBA) at first farrowing. Four categories were established in this respect.

| Groups depending on PBA No. at 1st farrowing |

7 PBA or less | From 8 to 11 PBA | From 12 to 14 PBA | 15 PBA or more |

Figure 1 shows the results obtained. You can see that the difference between groups is maintained throughout the productive life of the sow, with the purple group (15 PBA or more) being always, on average, the most productive in this regard.

Figure 1. Life performance of a sow based on the number of PBA at first farrowing

But... will these sows' performance be better in other aspects as well?

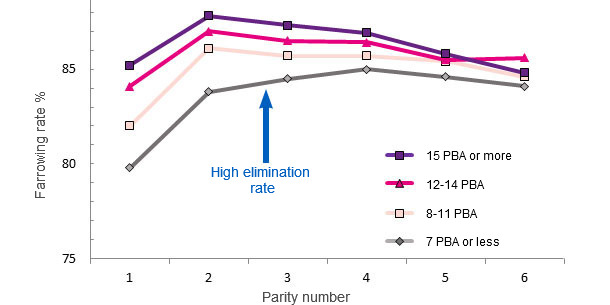

When studying the Farrowing rate (FR) in these groups, the results indicate that the sows 15 or more PBA in their first farrowing have, at the same time, higher farrowing rates, specifically up to parity number 4 (Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Farrowing rates during a sow's life based on the number of PBA at first farrowing

We also noticed that sows in the grey group (7 PBA or less) have a greater Culling rate in the farm, which is logical, since the sows with lower farrowing rates and prolificacy are normally removed earlier. This is the opposite situation to the sows in the purple group (15 PBA or more) that, thanks to being able to maintain this high FR, achieve a high Retention rate and longevity on farm, more than returning the investment the farmer made on them.

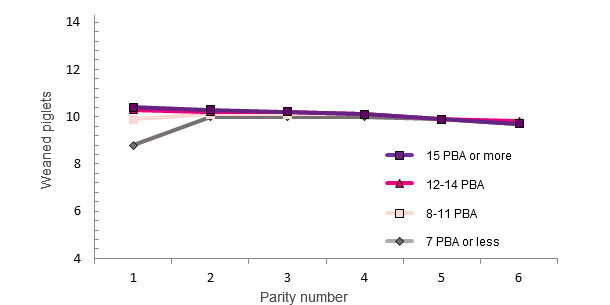

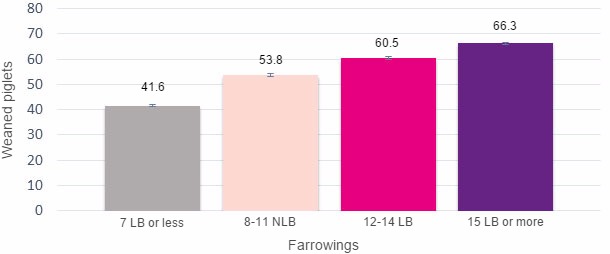

When analysing the results in weaned piglets based on the number of PBA at first farrowing (Figure 3), we don't see differences between groups, i.e., the sows with higher numbers of PBA do not wean more piglets during the rest of their productive lives, most likely due to the correct foster management in the farrowing room.

Figure 3. Weaned piglets during a sow's life based on the number of PBA at first farrowing

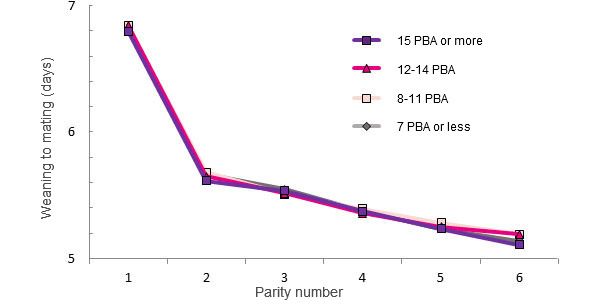

We also evaluated the weaning-to-mating interval based on the PBA at first farrowing, and the results show that there are no differences, i.e. the most prolific sows don't come into heat better than the others, which is consistent with the fact that there are no differences between weaned piglets, as explained above (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Weaning-to-mating interval during a sow's life based on the number of PBA at first farrowing

The summary of the above leads us to see production differences when considering the sows' entire life based on the number of PBA at first farrowing.

Figure 5. Piglets produced during a sow's life based on the number of PBA at first farrowing

In short, we can say that the outcome of a sow's life can be predicted on the basis of the number of PBA at first farrowing, and that the best sows' performance is continuously better than the rest. The findings of this study also lead us to reconsider sows' culling patterns, avoiding to prioritize elimination due to bad weaning or long weaning-to-service intervals, since they will not have a significant impact on their subsequent performance.