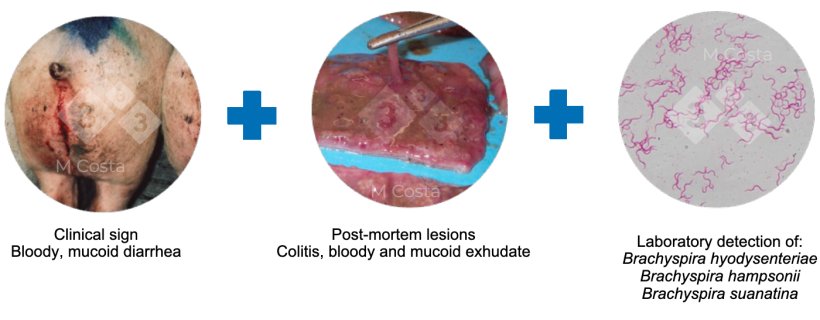

Bloody and mucoid diarrhea in grower-finisher pigs is the hallmark sign for swine dysentery (SD), a disease described in the 1920s. Pigs develop diarrhea following damaging and inflammation of their large intestine. It was not until the 1970s that, simultaneously, Glock et al and Taylor et al identified a spirochete as the cause of SD. This spirochete is now known as Brachyspira hyodysenteriae. Currently, it is known that swine dysentery can be caused by any of the three following agents:

- Brachyspira hyodysenteriae

- B. hampsonii

- B. suanatina

Noteworthy, it is now believed that pigs only develop mucoid and bloody diarrhea if infected with strains capable of destroying red blood cells (haemolytic). Haemolysis is therefore suggested as a proxy for virulence in Brachyspira. However, this should not be confused with haemolysis being the single required factor to cause SD (this is debatable and beyond the scope of this article). Since the 1990s, SD is controlled by antibiotic treatment and vigorous cleaning and disinfection of premises following the detection of any of its agents, particularly B. hyodysenteriae and B. hampsonii. Therefore, a strong selective pressure has been applied which is speculated to have resulted in the selection of variants with reduced virulence (weakly haemolytic, Figure 1). These strains can persist in pig populations not treated with antibiotics, causing subclinical or very mild disease.

But, what happens if the agent(s) is(are) detected, but there is no disease? In the past decade, this became a common scenario faced more and more frequently by veterinarians and producers worldwide.

To conclusively diagnose SD the association of clinical signs, post-mortem lesions and the detection of one of the agents using laboratory methods (PCR and culture) is required (Figure 2).

Detection of any of the SD agents has enormous consequences to an affected herd/system. This includes boar studs, nucleus or multiplier herds, and any other operation where animals are transported from the herd of origin to a different location. There is a high risk that animal trade will have to stop if any of the Brachyspira cited above is detected from clinical samples. This prevents spreading of the disease, but when no disease is apparent it is hard to justify such costly measure. Reports in the past decades described the detection SD agent(s) from pigs and herds with mild or no signs of disease at all (Card et al., 2019 provides an overview of these). This casts doubts on the accuracy of routine laboratory tests. In addition, finding the agent(s) without clinical SD poses the questions:

- Should animals leave this herd? Is it safe, for example, to ship gilts from a multiplier to other barns knowing that the multiplier is positive, but disease free?

This is a liability to the herd veterinarian and should not be taken lightly. There is no simple answer to these questions. The situation must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Below are suggestions to help address this scenario when it arises.

Since the genome of these variants is very similar to the virulent B. hyodysenteriae or B. hampsonii, their presence results in a positive PCR test. To confirm that a “mild” strain is present in a herd, the following outline the laboratory tests required:

- Culture and isolate viable Brachyspira from apparently healthy pigs;

- Verify the weakly haemolytic profile of the isolate by culture in blood agar plate;

- Speciate the isolate either by nox gene sequencing or whole genome sequencing (the latter is preferred as it provides further information about the isolate).

Currently, a “mild” strain isolated from a healthy animal should not be perceived as completely avirulent. Although clinical signs (e.g. diarrhea) may not be visible, it has been established that gut colonization by “mild” Brachyspira is enough to induce changes in the absorptive capacity of the large intestine (Costa et al., 2019). While not scientifically proven, it is possible that “mild” B. hyodysenteriae or B. hampsonii strains also affect performance in the grower-finisher stages, causing sub-clinical disease. “Mild” strains should also not be confused with “attenuated” strains. There is no evidence that they induce immunity against pathogenic variants. There is also no studies clarifying if “mild” strains would revert back into virulent strains, resulting in SD outbreaks.

Once the presence of a “mild” strain is confirmed, the decision making process begins by evaluating the risks that animal trading poses to potential clients or downstream herds, and the potential benefits of a strategy to eliminate the mild strain from the “contaminated” herd. Carrier pigs are an important source of swine dysentery introduction to a naïve herd. Stakeholders should be aware that elimination of B. hyodysenteriae/B. hampsonii is challenging and requires a long-term plan and staff commitment. It is expected that future research will help clarify the significance of “mild” strains, and their impact (or lack of) on production.