Diarrhoea is still a big problem for swine production, causing suffering in animals, necessitating antibiotic usage and result in economic losses.

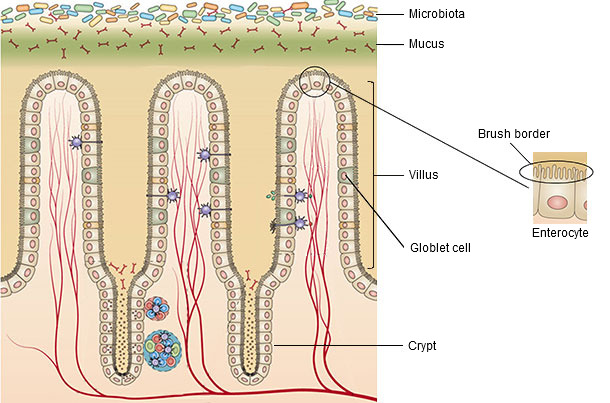

The small intestine is the longest part of the gastrointestinal tract and the major site of nutrient absorption but also an important site for enteropathogen colonisation. The mucosa is the layer in contact with the lumen of the tract and is able to increase extraordinarily its absorption surface due to the presence of finger-like projections called villi, which are covered by the enterocytes (Figure 1). The crypts are at the bottom of the villi and here is where the enterocytes differentiate for migrating up to the villi in a continuous replacement of these cells. There is also a viscous layer covering the villi, the mucus, which protects the mucosa from digestive secretions, pathogens and physico-chemical damage. It is formed by mucins secreted by the goblet cells distributed along the mucosa as well as antibacterial enzymes and antibodies. Thus, the mucus together with the layer of enterocytes is the first protective barrier of the intestine (van Dijk et al., 2002).

Figure 1: Structure of the small intestine mucosa (modified from Sommer and Bäckhed, 2013).

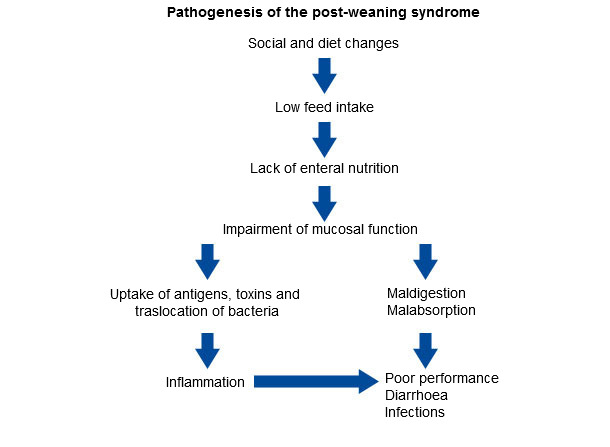

The weaning carries out two main critical changes for piglets; on one hand, the animals are separated from the sows, mixed and taken to growing pens, causing an acute stress on them; on the other hand, there is an abrupt change of feeding from suckling to consumption of solid feed. The consequence is a huge decrease in feed intake leading to a low luminal nutrient supply with consequences in health status and performance of piglets (figure 2).

Figure 2. The effect of weaning on mucosal barrier function, performance and health in piglets

(reproduced from Vente-Spreeuwenberg and Beynen, 2003).

During the first days after weaning, the integrity of the epithelium of the small intestine is compromised, showing up a reduction in villi length. As stated by Pluske et al. (1997) this villous atrophy can be associated with two different events:

- the increase in cell loss, accompanied by a faster maturation of enterocytes in crypts leading to a higher crypt depth (by microbial challenge, antigenic components of feedstuffs);

- the decrease in the rate of renewal of enterocytes due to reduced cell division in crypts (by fasting).

The quantity and quality of the mucus is affected by the changes in the epithelial integrity, and its damage would allow an easy access of pathogens or harmful compounds to the enterocytes (Vente-Spreeuwenberg and Beynen, 2003).

The apical border of the enterocytes, characterized by the presence of microvilli, is known as brush border and this is the site for nutrient absorption. The decrease in the number of mature enterocytes will result in malabsorption. Besides, the enzyme activity of this region is determined by the villus height and the maturity of the enterocytes (Vente-Spreeuwenberg and Beynen, 2003) and consequently, it will be affected by the changes described previously, causing maldigestion.

The enterocytes are interconnected by the tight junctions which control the paracellular flow (between cells), preventing the entrance of pathogens or toxics through the mucosa. The loss of integrity in the enterocytes monolayer facilitates the invasion of these molecules, causing an inflammatory response. All the mechanisms involved in the immune response will not be mentioned here, but they lead to undesirable effects such as anorexia, fever and inhibition of growth (van Dijk et al., 2002).

The fasting period is usually followed by a huge increase in feed intake inducing the stomach to empty its content faster to keep the low pH; a higher amount of bacteria can reach the small intestine, which is not yet recovered, facilitating its colonization by pathogens. In addition, the increase of the digesta in a situation of maldigestion and malabsorption will trigger a chain of events resulting in diarrhoea (van Beers-Schreurs and Bruininx, 2002).

To summarize, weaning triggers a series of changes leading to the decrease of feed intake and the deterioration of the intestinal architecture which finally results in infection, diarrhoea and low performance. Several studies are being carried on searching for strategies that minimize the impact of weaning on intestinal morphology and function; some of them are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Strategies minimizing the impact of weaning on intestinal morphology and function.

| Antioxidants to avoid feed rancidity | Dong y Pluske (2011) |

| Mold inhibitors to avoid presence of micotoxins due to mold growth | |

| Palatable stuffs (skim milk powder, whey, spray dried porcine plasma) | |

| Flavours and taste enhancers | |

| Supplementation with some aminoacids (glutamine, glutamate, arginine) | Lallés et al. (2004) |

| Administration of weaner diets in liquid form | |

| More digestible protein and energy sources |