Clinical presentation of diseases tends to change with time, this is because during its appearance and the first months or years of activity, a disease tends to behave in an epizootic manner, and later it tends towards a relative “stabilization” within an enzootic frame. This, of course, also tends to be the case with porcine circovirus. The course of the epidemiology of a disease usually has a very marked effect on the form in which it is clinically perceived at field level. While at the end of the 1990s and up until approximately 2003 PMWS was characterized by a very noticeable increase in the mortality percentage and a relatively high number of slow growth pigs on farms, this situation has lessened with time so that today these percentages are generally lower and in a more limited number on farms. This does not mean, however, that in a particular way there are not still concrete cases of farms with high percentages of mortality and slow growth animals.

Fig. 1. Pig clinically affected with porcine PCVD, with marked dorsal spine and long hair. Logically, slow growth is a characteristic finding of porcine circovirosis, but there are many other porcine diseases that present this symptomatology.

As already said, the clinical signs that have traditionally defined PMWS are mortality and slow growth (Fig. 1), but the disease can also be indicated by an increase in the size of the subcutaneous lymph nodes (basically inguinal superficial lymph nodes), body paleness (anemia), respiratory alterations (dyspnoea), diarrhoea and occasionally jaundice. The frequency of these findings should be considered variable. On some farms, together with an increased mortality, many respiratory problems are found; while other farms are characterized aboveall by digestive problems or simply by slow growth. In the majority of cases of PMWS a constant problem has been the lack of response to antibiotic treatment. This situation is what led to the belief from the beginning that this disease possibly had an immunosuppressor effect. It is also important to point out that the appearance of the clinical process tends to have an “individual” character; that’s to say that the animals that get ill are usually distributed in an irregular fashion within the affected barn. So, there often appear one or two affected animals per pen, in an apparently random manner, while the rest of the pigs in the same pen remain healthy with no sign whatsoever of the disease. Therefore, despite the fact that the horizontal transmission of the disease has been demonstrated (Epidemiology and transmission of PCV2 and of porcine circovirus), there is also an individual susceptibility, probably due to a genetic origin. The determining factors of this apparent genetic susceptibility are currently not known; however, it is not a question of a problem of the breed, but a question of the concrete genetic line in the context of certain farms. It should be remembered that porcine circovirosis is a multifactorial disease and animal genetics must be considered as one more factor in the puzzle of this pathologic entity.

Fig. 2. Lung affected with interstitial pneumonia of a pig with PMWS and co-infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). This “infectious combination” is relatively frequent at field level; macroscopically it is not possible to distinguish between these two infections, so laboratory studies are required to confirm the etiologic diagnosis.

The autopsy is always an important diagnostic element for the majority of diseases, and this is the same for porcine circovirosis. Besides certain lesions that we will look at later, possibly the most relevant pathological finding in cases of porcine circovirosis is the fact that when autopsying a number of animals there is generally no specific “pathological pattern” obtained. In other words, there is often an important variability among the autopsy findings, and in the same batch of animals there can be evidence of some with respiratory process, others with diarrhoea, others that die of a gastric ulcer and others that have no clear macroscopic signs for cause of death. This pathologic situation again suggests the immunosuppressor character of PCVAD. In the table that accompanies this article, there is a summary of the macroscopic lesions that most usually lead to the suspicion of a possible on-farm porcine circovirosis. On the other hand, as already indicated, many other lesions can be found depending on the concomitant diseases that the animals may suffer. It is not rare to find pigs that show signs of craneo-ventral pulmonary consolidation (catarrhal purulent broncopneumonia, symptom of a bacterial lung infection), gastric ulcer of the pars esofagica, mono or polyserositis (systemic bacterial infections), catarrhal or fibrino-necrotizing colitis, etc. When all is said and done, the clinical expression of a farm suffering from porcine circovirosis will end up being that which combines the entirety of the different diseases present, with a large majority of animals with slow growth and high mortality.

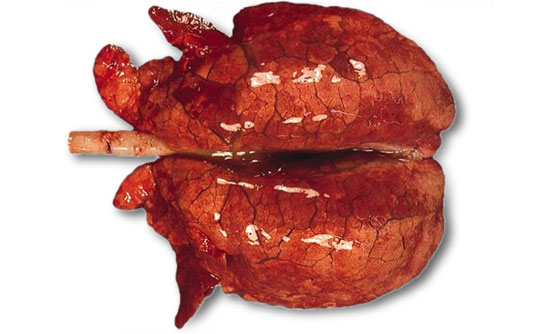

Fig. 3. Kidney of a pig with PMWS. The existence of whitish marks distributed in a general manner on the kidney is a relatively strong indication (in a clinical situation compatible with the illness) of a possible PCVAD. This kidney has, concomitantly, a renal cyst (arrow).

Therefore, from what we have already talked about, it should not be surprising that the definitive diagnosis of porcine circovirosis cannot be exclusively based on clinical and macroscopic findings. What clinical sintomatology and autopsy contribute are more or less consistent indications that we could be dealing with porcine circovirosis. Logically, the more evident the clinical picture and the higher the number of cases of animals with lesions associated directly with the disease (see table), the more likely it will be that we are dealing with PCVD. However, it goes without saying that the definitive diagnosis of the disease, at least at the moment, needs a histopathological study of the lymphoid organs of the affected animals (this will be the subject of the next article).

Summary of the macroscopic lesions that are most commonly associated with porcine circovirosis.

| Macroscopic finding | Interpretation |

| Pronounced dorsal spine (emaciation). | Common effect of the PCV2 infection in animals that clinically develop PMWS. |

| Absence of collapsed lung (Fig. 2) | Very probable interstitial pneumonia. Common effect associated with the PCV2 infection, although it can also be caused by distinct viral agents such as reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), or it can even be a combination of different viral agents. |

| Regional or generalized lymphadenopathy | Characteristic effect of the PCV2 infection in animals that clinically develop porcine circovirosis; it is due to a change in the subpopulations of lymphoid organs, with the granulomatose inflammation being resposible for the increase in the final size of the lymph nodes. |

| Serous atrophy of fat | Gelatinization of fat due to the mobilization of fat reserves in an animal that is losing weight and showing emaciation. This is a common effect in animals with porcine circovirosis that do not die in the acute/subacute phase and that tend to become chronic. It is not exclusive to this. |

| Kidneys with multifocal whitish spots (Fig. 3) | Most probably interstitial nephritis. This is a common lesion which is associated with the PCV2 infection, but it can be due to other causes, many of them badly determined. |

| Hepatic atrophy / Hepatomegalia | Ocassional or very ocassional effect of the PCV2 infection in animals that develop porcine circovirosis and that show jaundice. It systematically corresponds to a serious inflammation (hepatitis) of the liver. |