Due to the increasing importance of biosecurity around the world, we are fortunate to be able to assess the potential risks of contamination and spread of diseases from many farms in different countries in Europe, Asia, and America.

A priori, one may think that the situations encountered are very disparate, and it is true, one farm's scenario is totally different from the next's. However, there is a series of flaws in biosecurity that are observed constantly, transcending country, culture, and farm type or size.

In this article, we would like to present the four most common mistakes (illustrated with real examples) found on practically all the farms we have evaluated. Surprisingly, all of them are conceptual- much more related to the interpretation of biosecurity rather than to the lack of application of measures or to technical errors.

1. Double standard

It is very common to find that farms have a double standard in biosecurity linked to the belief that their measures/facilities/management are better than the rest. We will illustrate this with a very common example, loading bays.

A farrow to finish farm sends a portion of its pigs to slaughter and the rest are finished at external finishing units. The farm has two loading bays, one for sending pigs to the slaughterhouse and the other for sending pigs to the said finishing barns.

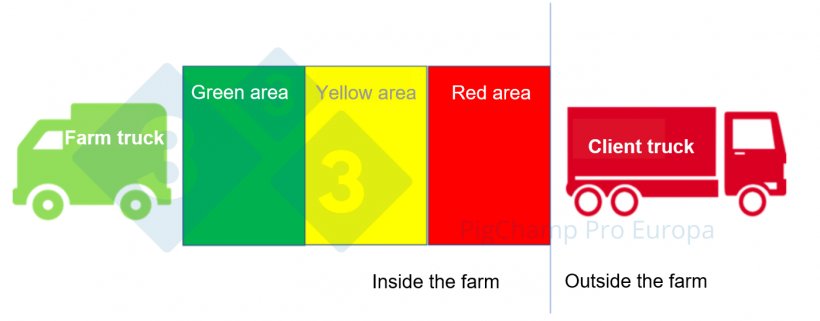

The loading bay used to send the pigs to the slaughterhouse has excellent biosecurity, being the classical bay, divided into three separate areas with automatic doors, showers for the personnel, etc.

Figure 1. Model of a loading bay with three zones.

On the other hand, we found that the loading bay for pigs going to the external finishing barns does not have any biosecurity measures; it is just a cement platform on the ground. When this difference is discussed, the person in charge of biosecurity argues that the second bay only has interaction with his company's trucks and that they can rely on them to be clean.

This is where double standards fail: it is possible that your company also makes mistakes and it is important to have the same preventive measures as with external companies.

2. Exceptions

The most common exceptions are made for special personnel and owners.

The vast majority of farms have implemented staff showers at the entrance, the use of farm clothing, and prohibit the entry of private vehicles onto the premises. However, we found that on many occasions these rules are not applied to all farm personnel. Here is an example.

A farm has different colored uniforms for each department: blue gestation, green farrowing, yellow finishing, etc. Throughout the audit, we observe how each work group is correctly in its zone following the color code; however, we begin to see personnel dressed in gray that move to all zones without changing their clothes: these are the maintenance workers. Similarly, the manager, dressed in black, shows the same pattern. (Image 2)

These types of exceptions are very common, but the underlying problem is really a failure to interpret the rule: the separation by color should be linked to the building, not to the type of work being performed. Figure 2. Exceptions to the color code for the maintenance team and the manager.

3. Confusing rules

The best biosecurity plan is useless if workers do not understand it.

In many cases, biosecurity rules are not easy to follow because they have many "sub-rules", conditions, or lack clarity, thus forcing the worker to think too much every time he or she has to follow them, which obviously greatly increases the probability of making mistakes. Here is an example also related to color coding.

A farm is designed with common hallways that distribute and connect each of the zones: gestation, farrowing, etc. The internal biosecurity rule implies that workers must wear footwear to walk through the passageways and change at the entrance of each of the zones to avoid cross-contamination. A priori, this is an adequate protocol; however, we found that there is no way to differentiate the footwear in the passageways from the specific footwear in each zone, since they are exactly the same (Image 3). This forces the worker to try to mark their shoes (marks that are erased every few days due to stepping in the footbaths) or to consciously think about whether they have changed their footwear or not.

Something as simple as marking existing footwear with colored ear tags for each zone would solve the problem. (Image 4)

Figure 3 (left). Footwear changing area between the hallway and farrowing room. Figure 4 (right). Marking footwear using colored ear tags.

4. Written protocols not followed

Almost all companies of a certain size are beginning to have written biosecurity protocols, both for external and internal biosecurity. However, it is not so common that these protocols are actually followed on the farm in the way they are described in the documents. Typical examples are the mixing of equipment from different zones, cleaning processes that are not followed, or the famous all in all out (AIAO) that is not really followed.

All farms are quick to answer "yes" to the AIAO question; but when you evaluate the real situation, you find that very few do it correctly. This is the case below: a protocol of marking piglets with colored ear tags according to the week of birth was implemented to check this, which resulted in the mixing of animals in the farrowing room with different colored ear tags. (Image 5)

Figure 5. Piglets with distinctly colored ear tags. The result of not complying with AIAO.

As discussed in the article, most biosecurity failures are related to confusion when designing or implementing protocols.

In our experience, external expert evaluation and having on-farm and in-company managers who are able to audit the standards is an essential starting point for biosecurity control. The final objective should be to generate a smooth working team in which opinions are compared, objectives are established, etc., and as a result, the probability of committing this type of biosecurity failure is reduced.