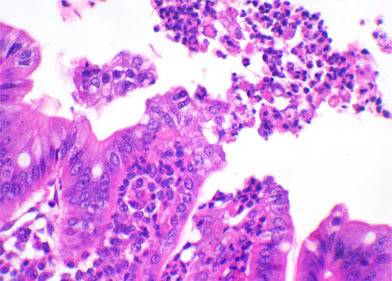

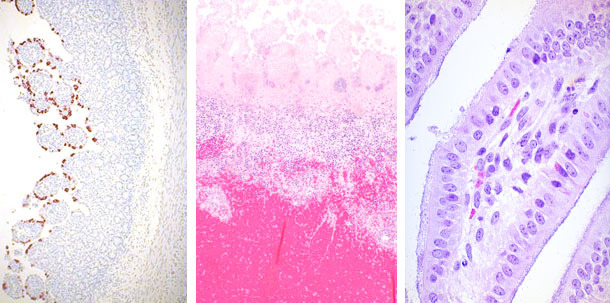

Histological evaluation of the intestinal sections mentioned in the previous article would allow the indication of a possible agent involved in the process, and in some cases, define the presence of infectious agents. For instance, villous atrophy could be caused by coccidian (I. suis), Rotavirus, TGEv, PEDv, Deltacoronavirus or even C. perfringens type A. If samples are from piglets older than five to six days, sexual or asexual forms of I. suis can be found in the cytoplasm of enterocytes in the tip of villi. If coccidian is not found, immunohistochemistry for Rotavirus or Coronavirus may be performed in order to detect the presence of virus antigen in enterocytes. Almost all cases of ETEC, histologic examination will allow the detection of a myriad of coccobacilar organisms attached to the enterocyte surface at the base or lateral part of villi. C. perfringens type C would cause a transmural fibrinonecrotic and hemorrhagic segmental lesion in the small intestine. C. difficile is the only infectious agent that would cause lesions in the large intestine. Mesocolonic edema is frequently observed. Reduction of goblet cells and an intense infiltration of neutrophils in the mucosa of the colon, that some times rupture the epithelium over layer similar to a volcano eruption, are the main findings in cases of C. difficile infection. C. perfringens type A is the most difficult to determine by histopathology, as it may cause villous atrophy, but not finding this lesion would not rule out this possibility.

Clostridium difficile

| Rotavirus | Clostridium perfringens | E. coli |

Bacteriology of fresh intestinal samples is important to be performed both in aerobic and anaerobic conditions. E. coli would grow easily in blood and MacConkey agars but even the pure growth of beta-hemolytic colonies are not a definitive diagnostic as it requires typification in order to demonstrate the presence of pathogenic factors, such as fimbria (F4, F5, F41, F18,…) and toxin (LT, STa, STb, STx2e, …) genes. This typification is most often performed by a multiplex PCR. Anaerobic cultivation is essential for C. perfringens type C definitive diagnostic, in association to molecular typification (multiplex PCR) for the detection of toxin genes, such as beta toxin. C. perfringens type A and C are identical in routine bacteriology. In the past, the detection of beta-2 toxin gene would be the marker for pathogenic C. perfringens type A strains, but recent studies by our group and by the group from Iowa State University have demonstrate that beta-2 positive C. perfringens type A strains are more often found in healthy than diarrheic piglets. As a result, the final definition and diagnosis of C. perfringens type A has been the most challenging one.

Viral isolation is difficult to be done in routine diagnostic. As a result, alternative tests are performed. Transmission electron microscopy for detection of corona or rotavirus particles is rarely performed and only used in some diagnostic laboratories in US. More often, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is performed in fecal samples for the identification of the segmented RNA of Rotavirus A, B and C, but the sensitivity is very much increased when multiplex PCRs is used. Multiplex PCR, using a different set of primers, has been very often used for the diagnostic of coronavirus in North America (PED, TGE and Deltacoronavirus).

Fecal material from the large intestine is valuable for the detection of toxins A and B of C. difficile. As this agent is part of normal intestinal microbiota, the detection of the above mentioned toxins by commercial ELISA kits is essential for its diagnosis. It is important to mention that these commercial ELISA kits were developed and optimized in human samples, and the sensitivity in piglet feces is low. As a result, sample size is relevant and the recommendation is to test at least 3 to 6 fecal samples from diarrheic animals. Based on the same principle, direct fecal examination is often used for the detection of coccidian oocytes; however, as the sensitivity is also low, the recommendation is to collect feces from three to five piglets per litter with clinical diarrhea, in a total to 10% of the litters between 7 and 21 days of age.

In conclusion, the detection of enteropathogenic agents in newborn piglets is always challenging. The main aspect that cannot be forgotten is the complete approach necessary to evaluate all possibilities. In that sense, samples have to be collected and tested to all possible agents that might cause diarrhea. PCR is a powerful tool, but do not relay all your coin in it. Old techniques such as histopathology would direct the interpretation of the results and broad your perspectives.