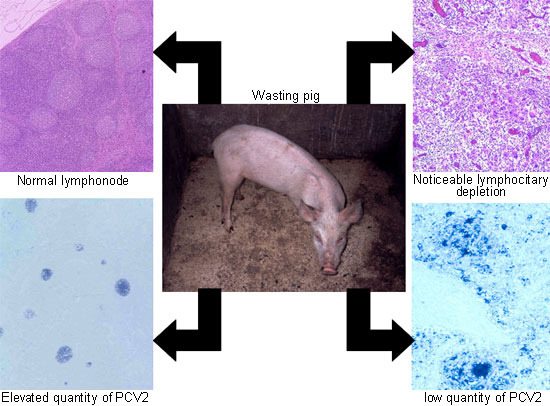

The criteria for diagnosing porcine circovirus (PCV) have not changed in the last ten years. To be precise, a pig, as an individual, is considered to be suffering specifically from PCV when it shows clinical symptoms characterized by slow growth and/or digestive/respiratory difficulties, histopathologic lesions which are characteristic in the lymphoid organs (moderated to a noticeable lymphocitary depletion with histiocitary infiltration) and the presence of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in a moderate to high quantity in these lymphoid lesions (Fig.1). However, the clarity of these diagnostic criteria is dependent on a series of related subjective aspects. The aim of this article is precisely to discuss those differentiating topics which are relevant from a practical point of view and which in some way elude the disease's definition.

Figure 1. The diagnosis of porcine circovirus is relatively simple, although it is based on the subjective evaluation of the pathologist. Therefore, in a wasting pig, the existence of noticeable lymphocitary depletion with histiocitary infiltration in lymphoid organs and an elevated quantity of PCV2 genome (photograph on the right) constitutes a diagnosis of PCV. If the wasting animal only shows slight lesions in the lymphoid organs and a low quantity of PCV2 (photographs on the left), then a diagnosis of PCV can not be established.

The first of these refers to when it is necessary to decide whether a farm is suffering from PCV. Currently, it is well known that a farm with good or very good productive parameters may still have sporadic cases of the disease.

Therefore, if we were being strict it would be practically impossible to declare farms to be "free" from PCV. It is because of this that there has been so much controversy in relation to the decision of whether a farm, a region or even a country (for example, Australia) is suffering or not from this disease. This controversy also logically comes from the ubiquitous character of the essential causal agent of the disease, PCV2. From this debate the necessity of establishing a "farm diagnosis" arose. With this the diagnosis of the process in individual animals will be combined with the epidemiologic situation of the herd. This "farm diagnosis" includes two important criteria which must both be adhered to:

- Significant increase in mortality and clinical signs that are compatible with PCV (clinical examination)

- Attainment of the individual diagnosis of PCV (laboratory examination)

In order to resolve the concept of “significance” of the first point a “statistical” approximation has been made using a chi-square test or the average mortality ± 1.66 x standard deviation (consult www.pcvd.net for more details). The problem with these calculations is that it is necessary to have previous mortality figures of the farm, and this is not always feasible. When these figures are not available an increase of more than 50% in relation to the average regional mortality is considered to be a sign of a possible case of PCV. However, there is another problem here, as attaining average mortality of a region or geographical zone is usually a difficult task. One might begin to believe that we are “splitting hairs” with the diagnosis of this disease, but this is the result of more than ten years of debate where the aforementioned controversy has been the norm, and where the “necessity” for maximum precision has surpassed the limits of normal diagnosis in pig diseases. In fact it should be emphasized that this first criterion of the “farm diagnosis” is very limited; its use makes sense in a context of epizootic disease (given that the mortality “problem” is compared with a previous mortality from one particular farm and this needs to be considered as normal) and it is not applicable to the enzootic situation which is currently the norm.

A second very relevant subject of diagnosis directly affects the veterinary clinic: selection of the individual pig for study (histopathology with detection of PCV2). In other words: how do we know that one particular pig is representative of a PCV? The answer to this question is not easy. It is known that a pig affected with the disease may develop a clinical picture of wasting and not die in the acute or sub-acute phase of the process, in a way that ends up with a chronic process developing. In this chronic phase, the histologic lesions in the lymphoid organs may have diminished to a point where they could be considered slight or non-existant, and in both these cases the individual diagnosis of PCV would not be produced (Fig. 2). Therefore, in order to “save” this situation of which animal will be representative for examination, it is necessary to select pigs in the most acute or sub-acute phase of the process (animal with no more than a week since the beginning of the clinical picture) and to study the maximum possible number of pigs. This last point will always be complicated due to the cost of the analyses. Ideally it would be recommendable to carry out the laboratory diagnosis on five pigs, given that this would guarantee that if PCV is a relevant disease on the farm (associated to more than 50% of existing mortality), at least one of the five animals is going to have a positive diagnosis with a probability of 95% (statistics again!).

Figure 2. With a view to making a suitable selection of animals for the diagnosis of PCV, animals with a chronic clinical infection must be avoided. A pig with cachexia is practically never diagnosed as PCV, and it cannot be established whether the animal suffered PCV in an anterior phase of the clinical picture (acute or sub-acute).

In short, these reflections have attempted to examine more deeply some of the key points of the practical diagnosis of PCV which are not usually dealt with in text books or scientific articles. Therefore it is important to emphasize more than ever that a wasting pig does not necessarily have PCV, and a negative laboratory diagnosis of PCV does not necessarily mean that the disease is non-existant on the farm. Despite the fact that these comments seem to be the custody of PCV, it should be remembered that they are also appliable to many other pathologic processes.