Broadly, the diagnostic tools available fall within the following categories:

1. Agent detectionDespite there being a range of diagnostic methods described, the availability of these tests varies from country to country depending upon the level of technology available, the focus of individual laboratories and the interests of vets and laboratory scientists working therein.

• Molecular-based methods (PCR) to detect M. hyopneumoniae DNA in lung tissue, nasal swabs, throat swabs or bronchial washes.

• Immunohistochemistry (IHC) to demonstrate M. hyopneumoniae antigen in histological sections of lung lesions.

• In situ hybridisation (ISH) to demonstrate M. hyopneumoniae DNA in histological sections of lung tissue

• Culture for M. hyopneumoniae from lung tissue or other respiratory samples.

2. Antibody detection

• Serological tests to quantify circulating levels of antibody to M. hyopneumoniae

Industry-based policies on health assurance testing and the methods recommended by leading pig veterinarians can also influence the availability of diagnostic tests that are offered by laboratories.

Diagnostic Scenarios

1) Suspected acute outbreaks of EP in a previously negative herd.

In this instance, the key factor is confirmation of whether or not the herd has broken down with M. hyopneumoniae. This can be done by submitting dead pigs or live affected pigs to the diagnostic laboratory for post-mortem examination. Fresh lung tissue can be tested by PCR and lung samples preserved in case further confirmation is needed through IHC or ISH testing.

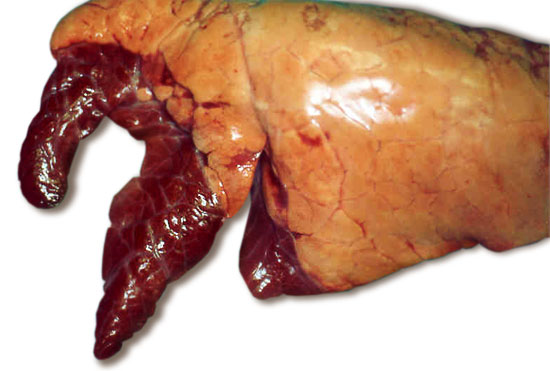

Fig 1. Typical appearance of lungs with enzootic pneumonia. The darkened antero-ventral lung lobes are consolidated due to the infection.

In addition to post-mortem examination, samples can be collected from live, affected pigs for PCR testing. In my experience, well collected throat swabs provide a higher diagnostic sensitivity rate than nasal swabs, and using a ‘nested’ PCR technique optimises the test sensitivity making this a highly valuable diagnostic tool. Pooling swabs in batches of 5 swabs per pool allows a representative number of pigs to be tested in a cost-effective manner.

The first set of blood samples for paired serology can be collected at this acute stage; ideally the pigs that are sampled should be tagged to enable the convalescent serum samples collected 3-4 weeks later to be matched correctly with acute samples on an individual pig basis.

2) Diagnosis of M.hyopneumoniae as part of ‘porcine respiratory disease complex’ (PRDC)

In complex pneumonia situations where one or more co-infections could be involved, extending the investigation and sampling protocol to include material for other tests is advisable. This includes fresh lung tissue for bacteriology and virology and or PCR testing for other agents. Histopathology on 3 representative areas of pneumonic tissue provides further insight into the nature of the pneumonic lesions. In chronic cases of M.hyopneumoniae infection there are certain features that can be described as highly suggestive of the diagnosis but the lesions are not truly specific, so will be reported with caution.

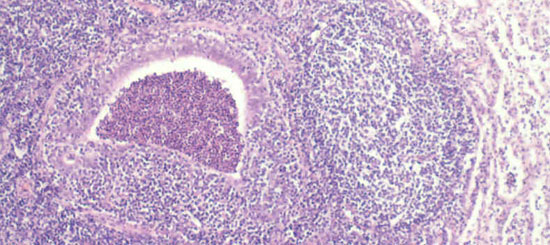

Fig 2. Chronic inflammatory reaction in and around the airways are typical features of chronic enzootic pneumonia.

Paraffin wax embedded histopathological tissues can be used for IHC or ISH to demonstrate the presence of agent(s) in association with lesions. Care should be taken to include ciliated airways within selected tissues in order to demonstrate the presence of M. hyopneumoniae most effectively. Where PRDC is a chronic problem in the herd, single sample serological testing can be carried out to screen for the presence of M. hyopneumoniae and other agents.

3) Screening healthy pigs for freedom from M. hyopneumoniae as part of a health assurance programme.

In addition to clinical inspection of herds and lung checks done on slaughtered pigs, representative numbers of pigs at high risk ages (i.e. growers or finishers) can be screened for M. hyopneumoniae by throat swabbing, as well as blood sampling for serology. Relying on serology alone is risky as there can be a lag-phase of up to 4-6 weeks before appreciable numbers of pigs show measurable circulating antibody after infection. PCR testing has a high degree of specificity and allows for earlier detection of infection. PCR testing can also be used effectively in EP-free herds that have been vaccinated as an insurance against the possibility of severe disease, in the event of break-down in a naïve herd.

Test accuracy

Factors concerning the specificity and sensitivity of tests should be borne in mind when interpreting laboratory results. The specificity of both the indirect and blocking ELISA’s for M. hyopneumoniae are good, but are not 100%. False positive results are known to occur but this can be kept to a minimum if laboratories have good internal quality control procedures and re-test samples giving low-positive titres to check the validity of results. Like-wise, laboratories carrying out PCR testing should have rigorous protocols to minimise the risk of cross-contamination and false-positive results, more especially so when using ‘nested’ PCR methods. Internal PCR controls are required to guard against false negative results.

IHC and ISH are specialist histopathology techniques and reading of the sections is the preserve of experienced veterinary pathologists. Non-specific fluorescence or staining can be confused with diagnostic fluorescence or labelling of agents unless pathologists are experienced in this field and suitable controls are used.

Although M. hyopneumoniae cultures were included in the list of detection methods, this is not practical for routine diagnostic use owing to its very slow growth rate, the need for specialist media and the frequency with which M. hyopneumoniae is overgrown by commensal organisms, usually M. hyorhinis. This expense and low sensitivity of M. hyopneumoniae culture renders it impractical unless isolates are specifically required for antimicrobial sensitivity testing.