The use of enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for the detection of proteins (antigens or antibodies) is one the most readily available diagnostic tools worldwide and is heavily used today in swine production medicine. The test is commonly used in surveillance and disease monitoring as well as a diagnostic tool. As swine veterinarians use this tool often, it is critical to understand how the assay works, what it is detecting, and its advantages and disadvantages when interpreting results. It is also important to remember that although the same technology is being used for different pathogens, there should be differences in how these results are interpreted.

Assay information

The ELISA assays are designed for the detection of antigens or antibodies against bacteria or viruses. Antigens are foreign proteins that stimulate antibody production (antigen = antibody generator). When thinking about antibodies, always think they are against proteins. In designing the assay, the manufacturer or laboratory decides what specific protein or proteins they want to target. If the ELISA is targeting the protein directly on the bacteria or virus, they are then called an antigen ELISA, whereas if the target is the animal’s antibody response to the bacteria or virus it is referred to as an antibody ELISA. Although there are ELISA assays designed to target only one or two proteins (antibodies or antigens), many actually target a large number of proteins. The assays can also be designed to detect a specific type of antibody response (IgG, IgM, or IgA) or a combination of these. Each of these types of antibodies has specific functions which are not part of the scope of this article.

The concept and process for antibody or antigen detection by ELISA are exactly the same. It starts with obtaining the targeted protein (antigen or antibody). For single proteins, there is a need for a separate process for obtaining a purified concentration of this single protein. Identifying which protein or proteins to target is a scientific and complex process. Ideally, the assay targets a single protein that is unique to the pathogen of concern (does not cross react with other pathogens), highly immunogenic (for antibody detection) or found in high concentrations (for antigen detection); it targets a protein which is known to be highly correlated to protection against disease, and always present. Unfortunately, many of these criteria are unknown and this single protein, which can be easily produced and found in the sample, or a mixture of multiple proteins (i.e. whole virus or bacteria) is often used instead. Although using whole viruses or bacteria as the target proteins can be easy, there are many opportunities for cross reactions with other pathogens.

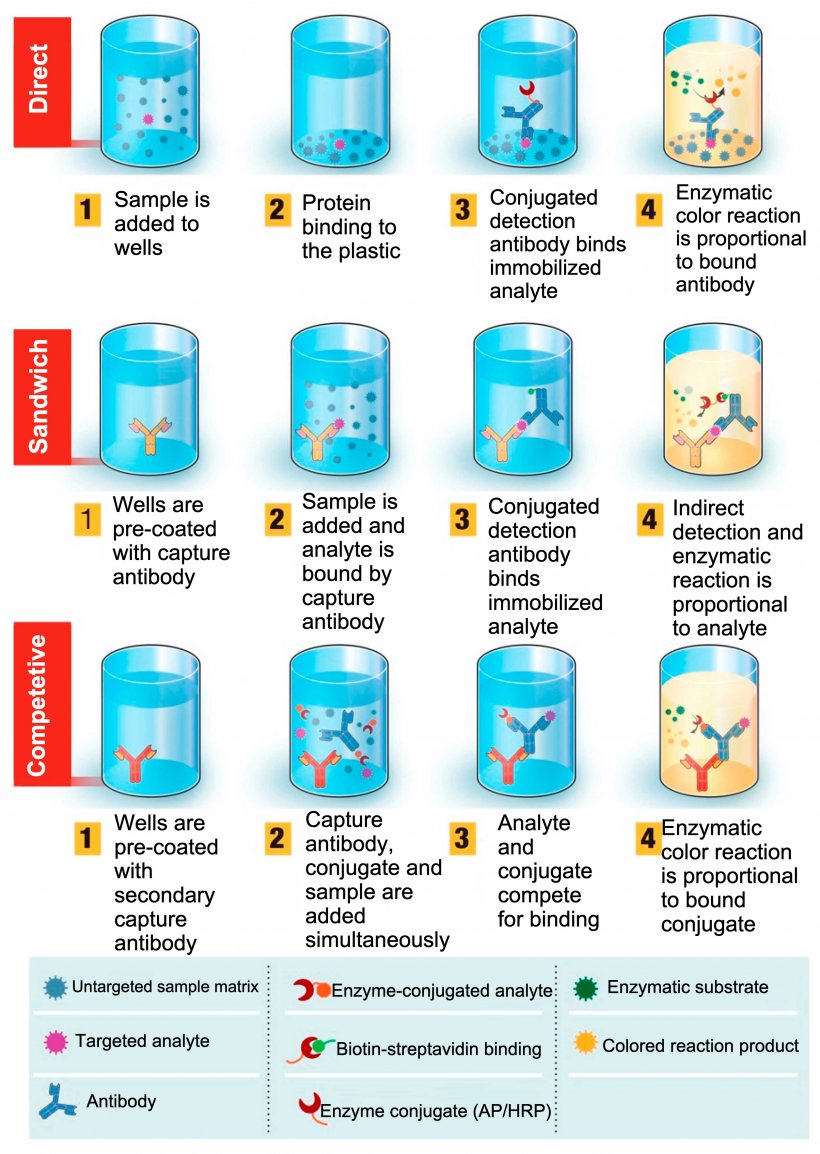

There are the general steps to the process (See Figure 1).

- Step 1. Pre-coat micro well plate with the targeted antigen(s) (for detecting antibodies) or antibodies (for detecting antigens).

- Step 2. Add sample to test and incubate to allow attachment between antigen and antibodies to occur.

- Step 3. Remove sample and add special antibodies that attached to opposite side of antibodies (bottom of the “Y” part of the antibody for antibody detection) or antigen (top of “Y” for antigen detection). The sample is then incubated to allow attachment to occur and washed to make sure any non-attaching (i.e., non-targeted) antibodies or antigen are removed.

- Step 4. Add antibody that is labeled with a detector that can fluoresce and will attach to special antibodies added in Step 3 (attach to bottom of the “Y” part of the antibody; same target for either antigen or antibody detection). The sample is then incubated again to allow attachment to occur and washed to make sure any non-attaching labeled antibodies are removed.

- Step 5. Add reagent that will trigger fluorescence of the labeled antibodies that remain and then allow to incubate to ensure attachment.

- Step 6. Sample is read, usually using a special machine at a specific wavelength to quantify color change (referred to as absorbance). There are some slight variations to this process on whether the assay is a direct, indirect, or sandwich ELISA with each of these assays have different advantages and disadvantages (not discussed here) but in the end they all report results the same; the higher the absorbance or color change, the higher the expected concentration of the target antigen or antibody in the sample tested.

The assay cutoff for each ELISA assay can be different and is pre-established by the manufacturer based on their desired targeted sensitivity and specificity. For a direct, indirect, or sandwich ELISA, any number higher than the cutoff is considered positive. For a competitive ELISA, any number higher than the cutoff is considered negative. For some assays, they also establish a gray zone to classify samples as “suspect” since the assay tends to have some “background” reactions (cross-reactions) that make it difficult to have a clear cutoff point.

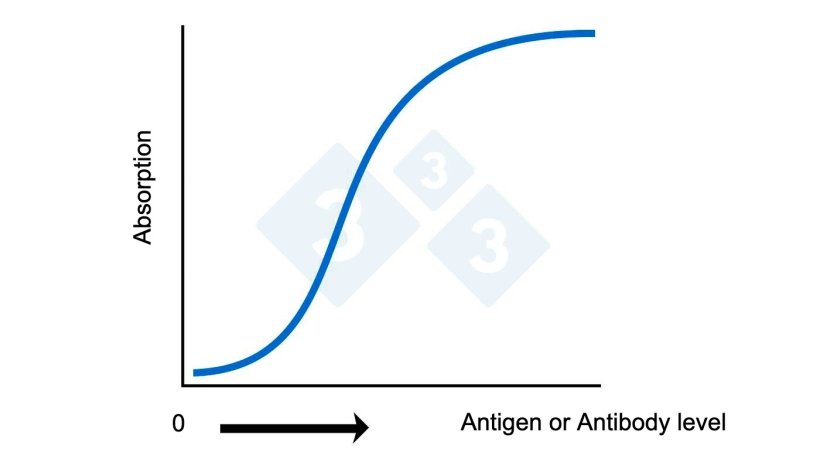

Results are usually, but not always, reported as a corrected S:P or sample to positive ratio which is corrected to background color change found in the negative control wells. Often antibody levels are referred to as “titers.” Although this is technically not correct, it can be justified from a big picture perspective. A key point is that when speaking about titers there is a direct mathematical relationship between values (a value of 20 has twice as many antibodies as a sample with a value of 10). With ELISA values, this direct mathematical relationship does not exist (See figure 2A). An ELISA of 2.0 does have significantly more antibodies than, and not just twice as many antibodies as a value of 1.0.

Pooling of samples for testing

Because ELISA assays are concentration dependent (directly correlate to concentration of targeted protein [antibody or antigen]) pooling for testing is strongly discouraged. Pooling can significantly increase the likelihood of missing a positive sample.

Some uses for ELISA assay:

- Detect presence of antibodies against targeted pathogen – Antibody ELISA – Most common use

- Determine exposure to pathogen

- Determine vaccination status of animal

- Determine timing of infection (change of antibody level) over time.

- Detect presence of targeted pathogen via detection of protein/antigen of targeted pathogen – Antigen ELISA