Influenza is a frequent infection on pig farms. The high percentage of farms that are seropositive to more than a single influenza A virus subtype proves this. From an epidemiolological viewpoint, we find two types of the disease: epizootic and enzootic.

The epizootic form is normally seen on farms with a high proportion of susceptible animals, and is characterised by a high morbidity, a very quick spreading and a low mortality. From a clinical viewpoint, the impact will be seen in animals of all ages, being especially important if it affects pregnant sows, because then we can see returns-to-oestrus and abortions due to fever.

On the other hand, the enzootic form is seen when there is a certain degree of immunity within the population, and it is characterised by a low infection rate. From a clinical viewpoint, this form can be apparently subclinical, although commonly, a recurrent influenza appears: a respiratory picture that appears repeatedly in each production batch during the nursery stage. Normally, in the case of enzootic influenza, the same strains(s) of virus(es) remain throughout time, so we can consider that the virus(es) become 'residents' on the farm. The impact of this form can be high in the nurseries, because it increases mortality and secondary infections throughout time.

A question normally posed in the case of enzootic influenza is: How is it possible that a virus that causes an acute infection in an animal is able to remain on a farm throughout time?

On the one hand, the gilts are a population that is susceptible to the infection if no immunisation measures are implemented, and it has been seen that the litters born to gilts have a relatively greater risk to be positive in the farrowing rooms than the litters born to multiparous sows. This would be compatible with a suboptimal protection level in these younger sows. Bearing in mind that in the current pig production systems the replacement rate can almost reach 50%, the replacements could play an important role in the persistance of this infection.

On the other hand, the colostrum-derived maternal antibodies (CDMAs) seem to provide a certain degree of protection, but we know that animals can become infected in the presence of CDMAs. What do we really know about the role of the CDMAs in the infection by the influenza virus? In a longitudinal study carried out in Spain, it was seen that the stage with the highest incidence of the infection was the farrowing stage. There were several surprising aspects: 1) approximately half of the infected animals showed CDMAs; 2) only a small proportion of them (<10%) seroconverted in the 3-4 weeks after infection; and 3) at least three out of 40 infected animals during lactation became infected again at 7 weeks old. All this would be compatible with other studies that show that passive immunity is not sterilising, and that those animals infected in the presence of CDMAs do not develop immunity against the challenge strain, whether homologous or heterologous, this allowing the animals to become infected again later on. Regarding the role of CDMAs in the spreading of the disease, several studies have been carried out both in North America and Europe. On the one hand, we know that the basic disease reproduction number (R0) is clearly reduced when the passive protection is homologous, even reaching levels that in some cases could stop the spreading and eventually, eliminate, with time, the infection from the farm. Nevertheless, when the infection is heterologous, the protection is much lower or even negligible. We must bear in mind that the circulation of more than an influenza strain is not infrequent on pig farms, and therefore, the scenario of an infection with an heterologous strain cannot be dismissed. Due to all the aspects, it is deemed that in the presence of CDMAs, the piglets could be the reservoir of influenza on a pig farm.

Lastly, farms are normally organised in production batches, so periodically (normally every one, two or three weeks) animals are weaned that will soon lose their CDMAs totally. The pigs are then susceptible to the infection and do not have protection against it, and it is then when recurrent influenza appears. Logically, from the viewpoint of time, the virus will always find animals on the farm that are susceptible to the infection, and this is especially important on farrow-to-finish or farrow-to-weaning farms, and therefore the virus can 'jump' between production batches keeping enzootic influenza on the farm.

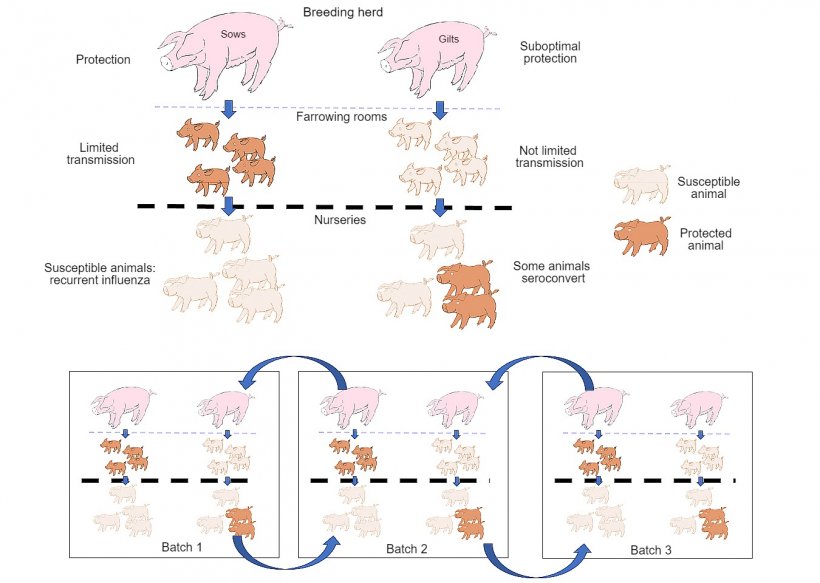

Summarising (see Figure 1), the different subpopulations on a pig farm allow the influenza virus to remain on the farm. The CDMAs have a role that can be considered controversial, at least. On the one hand, they can be useful when the infection is homologous, although a suboptimal titre (young sows) could be insufficient for the control of the infection. On the other hand, they could play a role in the persistance of the infection in the farrowing stage, and when the animals lose that immunity, there is a recurrent respiratory picture in the nurseries. Can we improve the immunisation protocols to reduce the transmission and impact of this disease? Can we reduce the risk of transmission with biosecurity measures? These are questions that must be studied to know all this aspects better, and this is essential in order to improve the control of this infection.

Figure 1: The spreading is further reduced in animals that obtain a better quality protection (piglets born to multiparous sows) than in piglets born to primiparous sows. In the nursery stage, the animals that have become infected in the presence of a certain level of maternal antibodies will not develop immunity actively, so the virus will be able to infect and cause recurrent influenza. Finally, the presence, at the same time, of different batches of animals with different ages facilitates the spreading of the virus between production batches, therefore perpetuating the infection.