Introducing Senecavirus A

Senecavirus A (SVA, formerly known as Seneca Valley virus) is a 30 nm non-enveloped RNA virus. It is the single member of the Senecavirus genus within the Picornaviridae family.

SVA applications and disease implications

SVA has been isolated from pigs since 1988 and it was reported as picornavirus-like particle until 2002, when the virus was isolated from contaminated cell medium and named Seneca Valley virus (Reddy, Burroughs et al. 2007). In fact, SVA has been identified as a non-pathogenic virus in human with oncolytic properties and its efficacy on cancer therapy is currently being evaluated in human clinical trials (Rudin, Poirier et al. 2011). The first whole genome sequence became available in 2008 (Hales, Knowles et al. 2008).

Investigations on the veterinary medicine field suggest that SVA circulates among domestic animals at least since the late 80’s. Anti-SVA antibodies has been detected in cattle, mice and pigs (Knowles, Hales et al. 2006). SVA has been suggested as a causative agent of idiopathic vesicular disease (IVD) in pigs (Singh, Corner et al. 2012, Leme, Zotti et al. 2015). Briefly, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and most governments consider reportable vesicular diseases in swine Foot and Mouth Disease virus (FMDv, Aphtovirus), Swine Vesicular Disease virus (SVDv, Enterovirus), Vesicular Stomatitis virus (VSv, Rhabdovirus) and Swine Vesicular Exanthema virus (SVEv, Calicivirus). Thus, clinical vesicular disease cases proven negative to those 4 viruses are considered “idiopathic vesicular disease”.

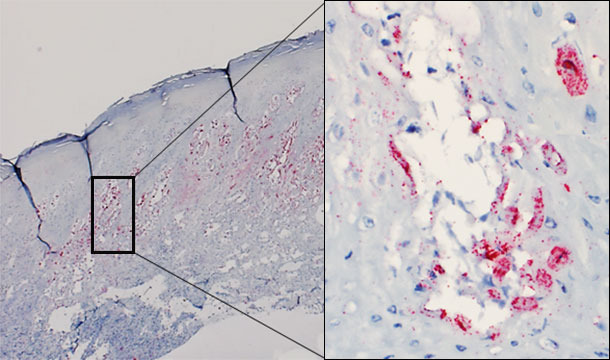

Despite several attempts, experimental reproduction of vesicular disease with SVA has not yet been successful. However, the virus has been demonstrated by in situ hybridization in vesicular lesions of affected animals (Figure 1). There is currently study under way to attempt to reproduce vesicular disease with a SVA recently isolated in the Midwestern USA from pigs with idiopathic vesicular disease.

Figure 1 – Skin biopsy of a vesicle from an affected pig. Presence of virus predominatly in the stratum spinosum of the epidermis. Intraepidermal vesicle: virus replicating in keratinocytes.

Association with ETNL, Brazil and USA

Recently (July 2015) Brazil has reported a novel clinical disease syndrome associated with SVA. Dr Vannucci and colleagues reported a neonatal losses syndrome, affecting piglets of 0-7 days of age. The fatality rate was higher (40-80%) in 0-3 days old piglets and lower (20-40%) in 4-7 days old piglets. Litters older than a week did not seem to be affected clinically. Once disease was established, it had a relatively fast onset of a wasting syndrome progressing to mortality, and the herd recovered to baseline mortality levels within 4-10 days. It is important to highlight that most piglets (>80%) had stomach full of milk/colostrum. Because of those characteristics, we proposed the term epidemic transient neonatal mortality (ETNL) (Vannucci, Linhares et al. 2015) Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Acute and transient characteristics of the epidemic transient neonatal mortality (ETNL). Left: typical appearance of an affected litter during an ETNL outbreak. Right: new litter from the same farrowing room 10 days after the peak of the mortality.

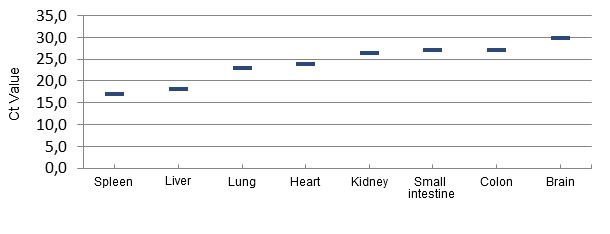

Extensive pathological evaluation of affected piglets from several herds in Brazil, and later in the Midwestern USA did not reveal any common/consistent gross or histopathological lesions that could explain the cause of piglet mortality. A consistent finding of herds developing ETNL was the detection of large amounts of Senecavirus A from multiple piglet tissues, including brain, blood and lymphoid tissues, indicating a widespread infection (Linhares, Rademacher et al. 2015) (Figure 3). SVA has not been found in tissues from non-affected piglets.

Figure 3 – Distribution of the virus by quantitative PCR in tissues of ETNL-affected piglets.

Alongside with ETNL syndrome, some herds also reported idiopathic vesicular disease with moderate to mild lesions in the snout and/or foot (coronary bands, interdigital area or footpad) (Figure 4). In other herds, no vesicular-like lesions were reported/seen, suggesting that SVA needs other contributing factors to establish disease (assuming that SVA causes disease). The IVD that accompanied ETNL also had a transient nature, with snout lesions healing within a few days and foot lesions healing within about 2 weeks.

Figure 4. Snout and foot lesions reported in idiopathic vesicular disease cases.

Epidemiological remarks and implications

ETNL was disseminated quickly in Brazil, being clustered in time and space. In other words, when a specific herd reported the syndrome, neighboring herds would also likely report ETNL, regardless of the production system, pig/person flow, genetic source or nutrition company. There were examples in Brazil and in USA of herds closed for >6months (not introducing external gilts/boars) that developed ETNL. Altogether, these observations suggest that ETNL and/or IVD were transmitted also by indirect routes.

So far, the first herds that reported the outbreak (September 2014) have not (to our knowledge) reported a re-break. In other words, it seems that ETNL was a “one-time deal”, at least after a year. Considering that most herds have ~45% replacement rate, every ~2 years most sows have been replaced, indicating that ratio between susceptible : immune/resistant animals might change significantly. That could cause waves of ETNL cases every 1.5 to 2.0 years.

Assuming ETNL and IVD were both caused by SVA, this virus has high transmission rate (regional level and herd level), it is highly immunogenic and have a long lasting (at least 1 year) immunity.

Recent molecular epidemiology work (Jianqiang et al. ASM science, accepted; Vannucci, Linhares et al 2015) showed that contemporary SVA isolates (USA and Brazil, ETNL and/or IVD cases) cluster separately from most historical SVA isolates, suggesting that SVA might have recently changed and somehow increased pathogenicity. Alternatively, the recent increase in clinical cases associated with SVA might be due to changes (increase) in transmission rate and/or environmental survival of SVA.

There is still need to understand how/where SVA “hides” between outbreaks and how it is transmitted between herds. In other words, can SVA remain infectious in feed ingredients? Is it airborne? Vector borne? Further research is needed to elucidate such questions.

Going forward

A variety of work/research is being conducted to address needs such as a) develop / validate an ELISA for SVA, b) confirm SVA’s role on ETNL/IVD, c) understand molecular epidemiology of SVA in Brazil and USA, d) SVA-disinfection procedures.

Foreign Animal Disease (FAD) investigation must be triggered at every case where IVD is detected to rule out the other 4 vesicular diseases (including FMD).

Acknowledgements

Dr David Barcellos, Iowa State University and University of Minnesota’s research and extension teams.