Introduction

Escherichia coli infections are ubiquitous in animals. There are many types of E coli, some are normal inhabitants of the intestine, but other strains cause a variety of recognised colibacillosis disease syndromes. These pathogenic E coli bacteria generally have fimbriae (pili) for attachment, enterotoxigenic exotoxins, endotoxins and capsules. There are various ways to classify E coli infections in pigs; this 2-part article will focus on some of the clinical syndromes. The list of major clinical syndromes due to E coli in pigs would include: neonatal colibacillosis, post-weaning colibacillosis diarrhoea and oedema disease; as well as colisepticaemia, coliform mastitis and urinary tract infections.

Neonatal colibacillosis

Colibacillosis due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) in suckling piglets often occurs at an early age, within the first week of life. It is most often associated with litters derived from gilts, which become infected quickly after birth, due to environmental contamination and inadequate maternal antibody levels. Vaccination of late pregnant gilts and sows should be performed routinely to induce lactogenic immunity for neonatal piglets against ETEC infections.

Post-weaning Escherichia coli diarrhoea

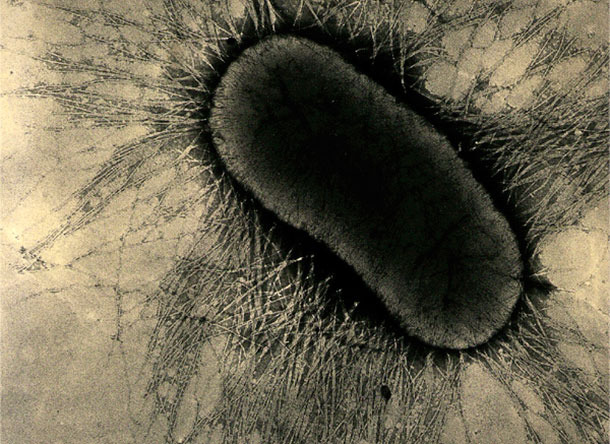

The enterotoxigenic E coli (ETEC) possess a combination of attachment factors and enterotoxins, which are both necessary for full intestinal disease to occur. The attachment factors on ETEC are specialized fimbrial or pilus proteins, which firmly attach to enterocyte glycoprotein receptors on the intestinal cells, see Figure 1 for illustration of these fimbriae. These receptors are only present for a limited time – usually until six weeks after birth in pigs. These attachment factors are now known as fimbrial antigens F4, F5, F6, F41 etc, although still frequently known by earlier designations of K88, K99, 987P etc. This attachment and adherence then allows the ETEC to resist normal gut movements and so colonize the intestine.

Figure 1. The attachment factors on ETEC are specialized fimbrial or pilus proteins,

which firmly attach to enterocyte glycoprotein receptors on the intestinal cells.

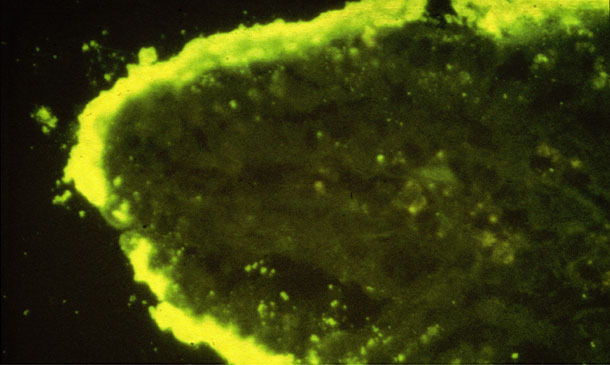

Figure 2 illustrates the attachment of dense colonies of E coli on an intestinal villus. The ETEC can then produce and “inject” their enterotoxins, such as heat-labile or heat-stable toxins, LT or ST. These toxins act on intestinal cells to cause hypersecretory diarrhoea, producing fluid outflow into the gut lumen, but without major cell damage.

Figure 2. Dense colonies of E coli attached on an intestinal villus (IFA).

Clinical signs - Clinical signs are nearly always in pigs around 2 weeks after weaning, with an outbreak of yellow-white, creamy-watery, projectile scours. The incubation period is 10 to 30 hours only; so many pigs will appear to become quickly affected in a group. This watery fluid diarrhoea has little solid feed evident and pigs rapidly show dehydration and loss of condition. It is often possible to press the abdomen of a suspect pig and see whether this diarrhoea is evident. Over a group of pigs, the diarrhoea can vary in consistency from very watery to a paste with a wide range of colour from grey white, yellow and green. Fresh blood or mucus is absent. Affected pigs are often from gilt litters. In severe cases, a pig is found dead with sunken eyes and slight cyanosis of the extremities.

Oedema disease

The E coli strains involved in oedema disease in pigs show similar characteristics to the ETEC in terms of epidemiology and pathogenesis of attachment to the intestine (see Figure 2). However, the strains are usually of the F18 fimbrial adhesin type and they also contain specific verotoxins or shiga-like toxins, such as Stx2e. These toxins enter the bloodstream of the pig and damage extra-intestinal blood vessels, producing neurological signs and gelatinous oedema of the head, eyelids, larynx, stomach and mesocolon.

Figure 3. Soft gelatinous swelling of the skin over the eyelids.

Clinical signs – The onset of disease is also around 2 weeks after weaning. The first sign is often the sudden deaths of a few pigs. The main clinical signs in the affected groups are dullness, ataxia, stupor, recumbency and dull waddling and running. When handled, pigs may respond with an abnormal high-pitched squeal. Soft gelatinous swelling of the skin over the eyelids is a prominent feature in many sick pigs, see Figure 3. So the affected piglets look like “drunk, squeaky puppies”. The illness lasts in each batch of pigs for around 2 weeks.