The current situation of the swine industry is marked by high production costs that directly affect the economic profitability of the business. That is why the main objective of today's pig farms is to achieve a balance between these high costs and the profits generated by production.

A sow farm's profitability can be measured using several parameters, but the most commonly used is the number of piglets weaned/sow/year. Thus, genetic advances on farms have been oriented to increase sow prolificacy. Sometimes this is a disadvantage due to the excess of piglets in proportion to the number of available teats, making the use of nurse sows necessary.

In the previous article we looked at the sows that wean zero piglets; in the present article, we will analyze the other extreme, the sows that wean at almost twice the farm average, the nurse sows. To do so we will use the PigCHAMP Pro Europa database.

The increase in prolificacy experienced in the last 5 years can be seen reflected in Figure 1, which shows almost one more piglet born per sow in 2021 compared to 2017.

Figure 1. Evolution of prolificacy 2017-2021.

However, in contrast to the increase in prolificacy, the increase in nurse sows over the last 5 years is not as clear (Figure 2), with the percentage of nurse sows averaging around 2%. This indicates that current animal husbandry probably relies on other management methods to manage the surplus of piglets from hyperprolific sows.

Figure 2. Evolution of the percentage of sows used as nurse sows from 2017-2021.

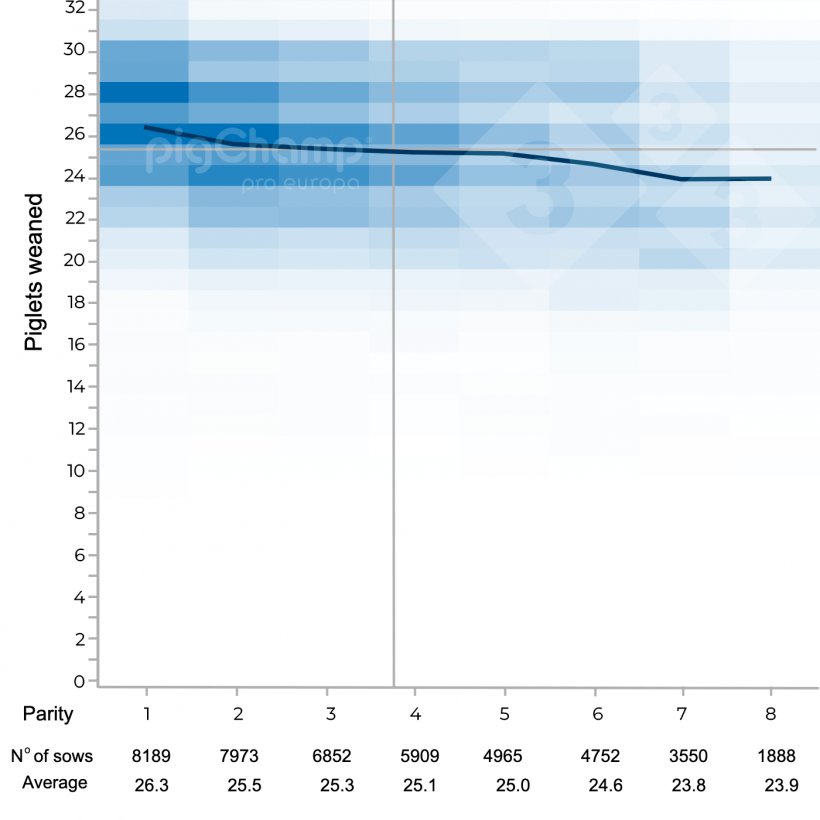

Regarding the age of sows that are chosen by producers to be nurse sows, the PigCHAMP Pro Europa database (Figure 3) reveals that the average parity is 3.8, with an average of 25.2 piglets weaned/sow. In addition, first parity nurse sows present the best data for total weaned; this figure decreases with increasing parity number. It is known that, as a general rule, the ideal nurse sows would be second/third parity sows, however, first parity sows could foster larger piglets to promote mammary development. At the other extreme, cull sows would have long, thick teats and poorer milk production, making them the worst candidates for selection as nurse sows.

Figure 3. Piglets weaned by nurse sows as a function of parity number 2017-2021.

The differences in nurse sow performance at subsequent farrowing compared to sows that had not been used as nurse sows are practically nonexistent (Table 1). Lactation length is longer in nurse sows as expected, however, in parameters that would indicate problems coming into estrus such as the wean-to-service interval there are no notable differences, and regarding the return rate, it is slightly higher in nurse sows than in sows that have not been nurse sows. The differences become more noticeable in the farrowing room data in the following cycle, with better data for sows coming from a weaning where they were used as nurse sows. This could be due to the fact that the dams with a better history, higher milk capacity, and more functional teats, are generally the ones selected to be used as nurse sows, hence the better data in subsequent farrowings.

Table 1. Reproductive parameters in nurse sows and non-nurse sows 2017-2021.

| Nurse sows | Non-nurse sows | |

|---|---|---|

| Average piglets weaned/litter | 12.6 | 12.3 |

| Lactation length (days) | 34.5 | 24.9 |

| Wean to service interval (days) | 6 | 6.1 |

| Sows serviced in the first 7 days (%) | 89% | 90% |

| Return rate (%) | 8.6% | 8.4% |

| Total born piglets/litter in next farrowing | 17.4 | 16 |

| Piglets born alive/litter in next farrowing | 15.4 | 14.3 |

| Conception rate (%) | 85.2% | 85% |

| Average age (parity) | 3.8 | 3.6 |

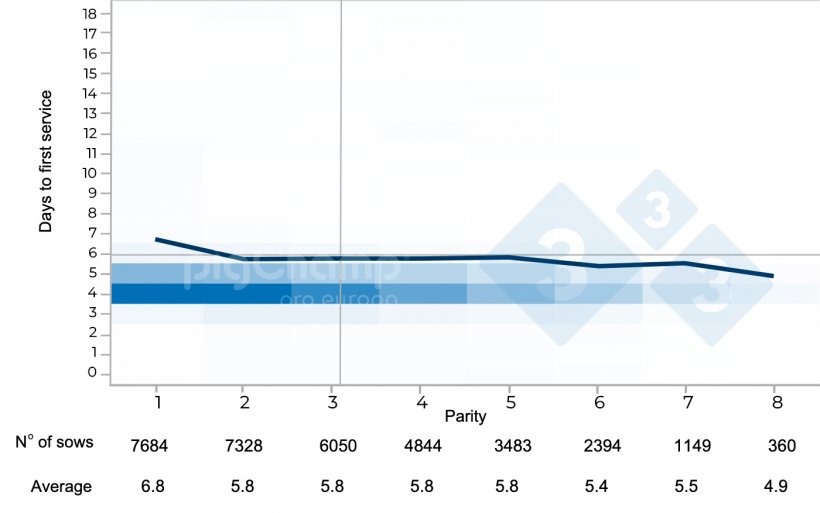

Coming into estrus after weaning for a nurse sow is the parameter that most concerns the producer, since the long lactations typical for a nurse sow could lead to loss of body condition or undetected estrus in the farrowing room, among other factors. In the following figure, it can be observed that nurse sows do not present greater difficulties coming into estrus after weaning than sows not used as nurse sows, with an average weaning-to-first service interval of 6 days. Similar to the rest of the sows, the nurse sows that present greater problems coming into estrus are first parity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Wean-to-first service interval of nurse sows as a function of parity number 2017-2021.

In summary, the use of nurse sows is a solution for saving the excess piglets from hyperprolific sows, and their proper management would ensure that their subsequent performance is not compromised. Selecting the nurse sow will not only depend on the history of the particular sow, but it will also be necessary to take into account the different parameters that would be negatively affected when sows are used for nurse sows, such as the wean-to-service interval, number of farrowings/year, and the extra time a nurse sow spends occupying a place in the farrowing room, as well as the cost that all this entails. According to the data presented, using parity 2 to 4 sows would be most advisable, as they are the ones that least penalize the overall production data.