Introduction

Exudative Epidermitis (EE) or greasy pig disease is a bacterial skin disease that can occur in any age animal but is most common in suckling and recently weaned pigs. The disease has been recognized in most pig‑rearing countries of the world and will occur on most farms from time to time. Staphylococcus hyicus, the bacterial cause of EE can be recovered from nose, eye and skin of healthy pigs and from the vagina of healthy sows. The organism can persist for several weeks in the barn environment.

The disease is most dramatic in pigs that are born to non-immune sows. Skin trauma from fighting, sharp teeth, abrasive bedding and abrasive penning can lead to perforation of the protective layers of the skin. The lesions of EE are associated with the heat labile exfoliative toxins produced by the S. hyicus bacteria. The changes in the skin are accompanied by increased sebaceous secretion and serous exudate. The mortality associated with EE is primarily associated with dehydration although septicaemia and arthritis may also occur.

History

This particular case occurred in a multisite farrow to finish operation in South Western Ontario, Canada. Throughout this case there were no significant clinical signs of EE at the sow site. This included absence of clinical signs in internal replacement gilts that were housed in a nursery and grower barn located at the sow site. The disease occurred initially at one of two continuous flow off site nurseries. Several months later clinical problems increased at the second nursery.

Photo 1 Acute localized EE

Pigs were weaned once per week at three weeks of age. The original history was that there were no clinical signs of disease until approximately 10 to 14 days post-weaning. Closer observation revealed that within a few days after weaning pigs were developing localized lesions in the cuts and scratches associated with fighting. Baby pig teeth clipping was not practiced at this farm. Some pigs showed only localized lesions (Photo 1). Other pigs would show clinical signs of lethargy and rapid development of a generalized reddish skin colour. The skin was hot to the touch. Thin, pale brown scales of exudate developed in the arm pit, groin, belly and behind the ears. This exudate would then spread to the entire skin surface (Photo 2). Within a few days the skin became dark in colour and greasy in texture. Severely affected piglets experienced rapid weight loss and death often occurred within a few days. There was no noticeable itching. Growth depression was quite severe in some of the survivors and chronic poor doing pigs were euthanized. The post weaning mortality was normally 2.0 %. The post weaning mortality increased to 4.0 % with some barns reaching up to 9 % mortality. This problem persisted for approximately 13 months. Almost all of the increase in mortality in this case was attributable to the EE.

Photo 2. Acute generalized EE

Diagnostics

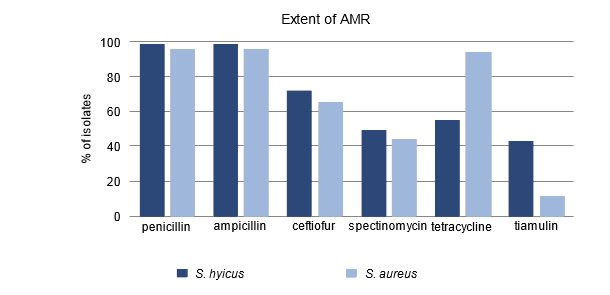

Swabs of clinically affected pigs initially yielded S. hyicus in large numbers. Subsequent swabs identified Staphylococcus chromogenes. This organism is genetically very similar to S. hyicus and is also capable of producing exfoliative toxins. The antimicrobial sensitivity pattern indicated that there was resistance to penicillin but the organism was sensitive to trimethoprim/sulfa and tiamulin. The finding of resistance to penicillin was consistent with recent research which showed that resistance to penicillin in Ontario S. hyicus isolates was common (Figure 1). Further analysis at the University of Guelph identified that this particular isolate was also zinc resistant. Additional post mortems and diagnostics were carried out in order to rule out whether or not there were other underlying diseases that were exacerbating the problem. No other disease issues could be identified.

Figure 1. Percent of isolates resistant to antimicrobials

Intervention

EE is a classic multifactorial disease. Although identifying and correcting a single factor can occasionally yield results, the focus in this case was to improve both passively acquired maternal immunity as well as the local immune barrier that was provided by intact skin. At the same time it was recognized that it was important to reduce the bacterial challenge level.

A review of feed formulations and the amount of each feed budgeted per pig did not reveal any problems with the plan. Closer attention, however, needed to be paid to correctly allocating the budgeted amount of each feed to the pigs during specific stages of growth. Feed was kept fresh and palatable and all available feeder space was kept operational in order to minimize fighting for access to feed. Once the zinc resistance was identified the added zinc complex was removed from the diet.

The normal procedure in these nurseries had been to remove the front gates from the pens in order to allow for increased comingling and early colonization of the weaned pigs with as many of the “little bugs” as possible. These “little bugs” normally included Streptococcus suis, Haemophilus parasuis and Actinobacillus suis. The decision in this case was to close the front gates with the goal of preventing spread of EE. The pens were kept locked down for 4 weeks post weaning and then opened into larger groups. Once the pigs reached 4 weeks postweaning there were very few new cases of EE.

There was some considerable discussion about the contribution of baby pig teeth to the number of cuts and scratches associated with fighting. The nursery operators felt strongly that the teeth needed to be clipped if we were going to be able to solve this problem. Several batches of pigs had their teeth clipped on an experimental basis. All agreed that , at least in this situation, the teeth clipping did not reduce the incidence or severity of EE. Teeth clipping was discontinued.

Water flow was assessed. Some drinkers were not working properly. Drinkers were repaired and set to provide a minimum flow rate of 0.5 liters / minute. The goal here was to avoid spraying and wetting the skin while providing adequate flow and drinker numbers such that aggression around the water nipple would be minimized.

Relative humidity was targeted at 70% for fall, winter and spring and additional heat was added in order to maintain a minimum ventilation rate. Rooms were heated to a target of 28ºC on entry. Insulation levels in the attic were checked. The pigs were kept dry and draft free.

The rooms were started with an initial overstock of about 10 % in order to allow establishment of a hospital pen and rapid removal of initial clinical cases. Pigs with red and inflamed skin were removed to the hospital pen to prevent spread. At closeout of a room, recovered pigs moved to the finisher and not back in with younger pigs.

Sanitation was reviewed. Soaking was initiated immediately after pigs were shipped with washing on the next day. There was increased attention to detail on washing. An alkaline cleaner was used for degreasing and biofilm removal. Acidic cleaners were used initially for some mineral removal. Disinfectant applicators were calibrated. Several disinfectants were tried with no one disinfectant appearing to be any better than the others. A minimum drying time of 24 hours prior to arrival was achieved.

Individual affected pigs were injected with trimethoprim sulfa at label rate for 4 days. A trimethoprim sulfa water soluble preventive medication was used from day of entry to 21 days post entry. This was reduced to a pulse program, with 3 days on and then 4 days off for 3 weeks post entry. Eventually this medication was switched to treatment only on an as need basis.

The starter rations were medicated with chlortetracycline at 110 ppm, sulfamethazine at 110 ppm and procaine penicillin at 55 ppm. The final ration in the nursery was medicated with procaine penicillin at 110 ppm. No other feed medications were used.

A topical spray containing a mixture of trimethoprim sulfa and mineral oil was used on a preventive basis every 4 days. In addition the topical spray was applied at the first signs of an increase in the number of new cases. In a room of 500, if there were 3 new cases in the morning with an additional 3 new cases in the evening the entire room was sprayed.

Prior to the outbreak a S. hyicus isolate had been added to the pre-farrowing farm specific autogenous vaccine. This custom vaccine was prepared using bacteria that were isolated from this specific sow, nursery and finisher pig flow. By vaccinating sows prior to farrowing colostral passive immunity in the piglets was enhanced. S. hyicus and S. chromogenes isolates from the nursery were subsequently added to the pre-farrowing autogenous vaccine. No immediate improvement was seen when pigs from immunized sows reached the nursery. The pre-farrowing autogenous vaccine is still being used. Gilts are vaccinated twice prior to farrowing and sows receive a single booster vaccine prior to each subsequent farrowing.

Discussion

The nursery performance has returned to normal levels but not without a considerable increase in management input above and beyond what was previously required to maintain control. The severe clinical signs were confined to one of two nurseries in the beginning and it appears that movement of pigs and people could explain the movement of the disease to the second nursery. There was never any evidence that the more "problematic" isolates made their way to the sow herd. If these isolates were absent from the sow population there would have been little assistance from colostral antibodies in controlling the disease at the nursery. In theory a complete depopulation and repopulation of the continuous flow nurseries could eliminate the more problematic isolates. It could be argued that this problem was protracted because of the “absence” of the problematic bacteria from the sow herd.