Weaning of piglets is a stressor with major implications for both health and performance. Interruption of nutrient intake plays a dominant role in this, as this predisposes the animal to gut health problems. In fact, E. coli infection trials at Nutreco’s Swine Research Centre showed that the consequences of this infection were determined by the amount of feed eaten before the infection occurred: when below maintenance, animals got seriously sick, and when above maintenance, animals barely suffered from the infection. The feeding behavior is thus crucial to its health, and a better understanding thereof may lead to suggestions for reducing the weaning stress.

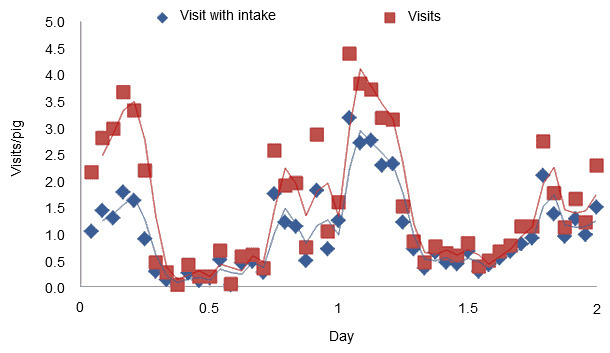

Trials with electronic feeding stations and piglets weaned late morning and with access to creep feed prior to weaning provided some insight into feeding behavior. Somewhat surprising, piglets had no difficulty finding the feed; nearly all pigs (95%) put their heads into the feeder within 4 hours after weaning. Half those visits, though, did not result in feed disappearance (Fig. 1). The fraction of effective feeder visits increased to 80% after 2 days (Fig. 1). Hence, it took much longer for the pigs to consume the equivalent of one meal (10 grams; based on a feed intake of 150-200 g/day in the first days after weaning and 15-20 feeder visits/day): 45% of the piglets did not do this on the day of weaning.

Figure 1. Visits to the feeder and visits in which feed disappears in the first two days

after weaning of piglets that had access to creep during lactation.

The data also show clearly that the pigs stopped looking for feed at night (Fig. 1), despite the fact that during lactation they frequently nursed at night. This suggests that the nursing bouts at night are initiated by the sow but that intrinsically the piglet has a day-night rhythm. Torrey (2004) experimented with waking up newly-weaned piglets at night using recordings of sows grunting. This, however, led to an increase in water intake rather than feed and was without positive effects on performance.

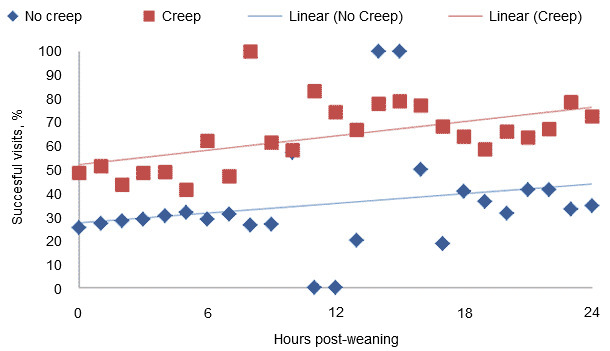

An interesting question is what happens the first times the piglet puts its head in the feeder. Careful analysis of the feed disappearance records show that actually very small quantities of feed are disappearing in those early visits (96% of the animals made feed disappear in the first 4 h after weaning), but these are often followed by a period of feed refusal. In nearly half the animals, substantial feed intake is not initiated till the next day. This behavior fits with food neophobia. Animals that are starving in the wild and confronted with a novel food source will typically only sample this new food, despite their hunger. Only after ‘experiencing’ that this new food doesn’t make them sick will they come back and consume more of the novel food. The feed intake patterns of the piglets seem to match this; many piglets consume only a small quantity of feed in the first hours after weaning (grams), but only after confirming that this feed is safe they will consume an appreciable amount and ultimately shift to a regular feed intake pattern. Observations with individually housed piglets fit with this food neophobia concept: typically 5-10% of piglets will refuse to eat for days, except for a minute feed sampling at weaning. This with severe consequences for their own health. Only after showing that the feed is safe by mingling them with other piglets that do eat or after providing them with a completely different diet will they resume feed intake. If food neophobia indeed plays an important role in newly-weaned piglets, then it is once again a signal that we need to teach the piglets to eat their post-weaning diet before weaning and we need to match the palatability of diets pre- and post-weaning. Evaluating feeding behavior in pigs managed with and without creep feed showed that the pigs that had creep feed had twice the number of effective feeder visits (49 increasing to 73% vs. 25% increasing to 35%) in the first day after weaning (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Successful feeder visits of piglets with and without access to creep feed in lactation.

The variation at night is caused by a low number of feeder visits.

These data also beg the question at what time of the day piglets should be weaned. Weaning early in the day would give them the most time before nightfall to learn how to eat. Weaning early afternoon may give the piglet a chance to sample the feed before nightfall, and the next morning they have experienced that the feed is safe and they can start a regular feed intake pattern. Trials to test the optimum time of day of weaning are few: only one study from Ogunbameru (1992) was found in which evening weaning (8 pm) resulting in piglets that were nearly 1 kg heavier 28 days post-weaning as compared to weaning at 8 am.

Conclusions

Feed intake patterns post-weaning show that piglets have little difficulty finding the feeder. However, especially piglets that were not exposed to creep feed do not recognize the feed as food. Some sampling seems to occur in those animals before they develop a normal feed intake pattern in the days that follow. During this time period there is a high risk of piglets becoming ill which could lead to persistent feed refusal. Training the piglets to eat pre-weaning with a high quality prestarter like should thus facilitate their weaning transition and reduce the risk of health complications. Ideally, the creep feed and prestarter feed are matched for palatability such that the piglets don’t experience it as a new feed. On top of that both the creep and prestarter feeds should be formulated for palatability above anything else.