The modern sow, a product of decades of genetic improvement, is undoubtedly an exceptional animal. Her reproductive capacity is impressive: she can conceive and farrow large litters, rear them to weaning, and come into estrus again within a short time. However, this potential is not always achieved under commercial conditions, where decreased performance is frequently observed. Among the determining factors, one of the most significant is feeding management in the farrowing room, both pre- and post-farrowing.

The knowledge gained in the last decades on this issue has been conditioned by a factor that may seem minor but is of great importance. Until recently, we have fed sows according to our criteria. In other words, we fed them ourselves, generally in 2-3 feedings per day, coinciding with the working hours on the farm (morning - early afternoon), regardless of how hot it was (summer and winter can be very different in many countries) or whether they ingested all the feed or not, since the leftover feed was not always cleaned between feedings, instead of giving them the opportunity to feed themselves according to their own will. In addition, water has been administered with different criteria without a clear general guideline (inside the feeder or in a separate bowl, with or without a drainage hole in the feeder, or at different flow rates, among others), therefore it has not been optimal in most cases.

In recent years, knowledge about the natural behavior of animals has increased. In time, or perhaps because of it, we have tools that allow us to greatly improve the procedures that optimize results in the farrowing room. In this article, we will refer to two recently described factors related to the temperature of the water supplied and the management of pre-farrowing feeding.

Recently, Tajudeen et al, 2022 studied the impact of water temperature on sow and piglet productive performances, comparing fresh water (15 ºC) with warm water (25 ºC). Sow feed intake was 8.9% higher with fresh water, with less weight loss at the end of lactation (2.7%) and less backfat loss (3.1 mm less). The impact on the litter was also clear, weaning 5.3% heavier piglets (+321 g) and 5.3% heavier litters (+3.19 kg litter). The experiment was done with weaning at 21 days so, in my opinion, with later weanings, which are done in the EU, it is quite likely that these differences would increase.

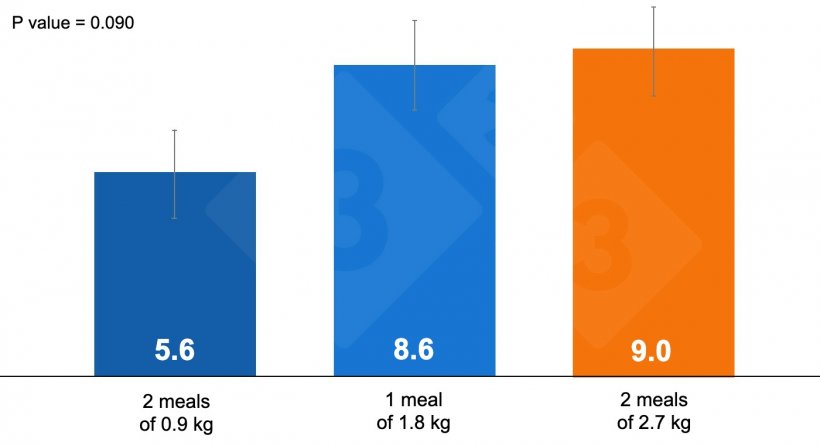

Regarding feeding management in the 7-day pre-farrowing period, recent work by Gourley et al. in 2020 shows the great impact of pre-farrowing feeding on what happens after farrowing. Simply dividing into two meals instead of one, even if it is a small amount, as used daily by the authors (1.8 kg, graph 1), significantly reduces the number of stillbirths from 8.6 to 5.6%.

Graph 1. Impact of pre-farrowing feed management on stillbirths.

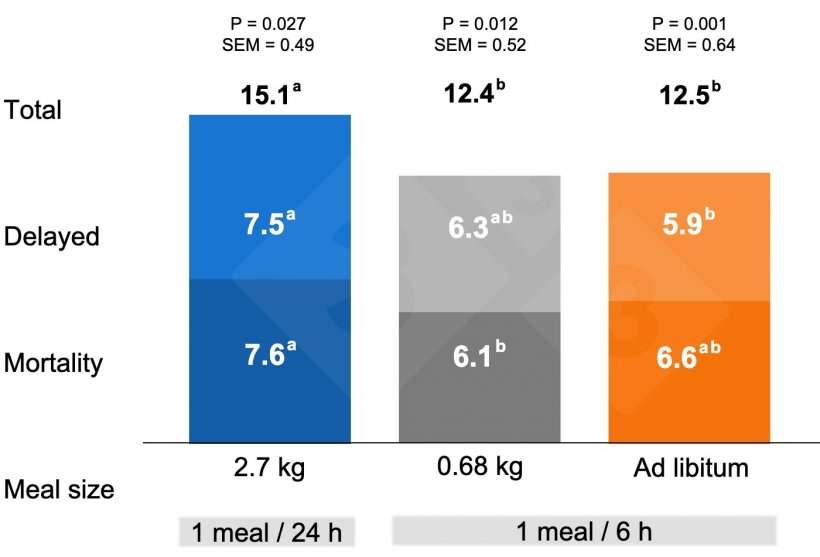

Even more interesting is the fact that administering the daily intake during pre-farrowing in four meals improves both preweaning mortality and delayed piglets, regardless of the amount administered, as shown in Figure 2.

Graph 2. Impact of pre-farrowing feed delivery method on preweaning mortality and delayed piglets.

The use of precision feeding systems (Photo 1) that allow feeding in a supervised ad-libitum (within a range, as pure ad-libitum leads to high feed wastage) with the opportunity to do so in several feedings and to let the sow decide how (intake pattern) to eat, even in the pre-farrowing period, offers us great value by reducing the risk of increased mortality and delayed piglets.

If we also pay attention to water temperature, supplying water as cool as possible and at least avoiding having the pipes or tanks in the sun, we can begin to control some of the risk factors that limit modern breeding sow performance in the farrowing room.

In the next article, we will review other factors that have a major impact on lactation feed and water management that determine performance in the farrowing room and also in the sow's following production cycle.