It is estimated that our pigs have a total of 1010-1012 bacteria in the intestine, a number that multiplies by 10 the total number of cells in their body (Luckey, 1972). Therefore, it is essential that we take into account this bacterial component when designing the diets for our animals, because by means of a healthier and more favorable microbiota for the pig, we can directly promote a more efficient digestion process, improvements of the immune system and an increase of the production yields.

The influence on the microbiota can be exercised in the following ways:

Modifying the availability of nutrients for certain species of bacteria

In general, the bacteria of the proximal colon have a great amount of nutrients, coming from undigested residues of the diet, and this substrate is reduced and limited as approaching to the distal regions.

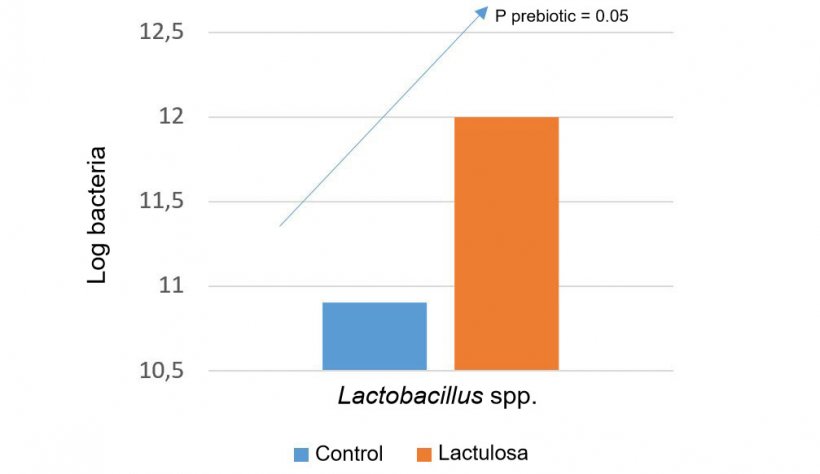

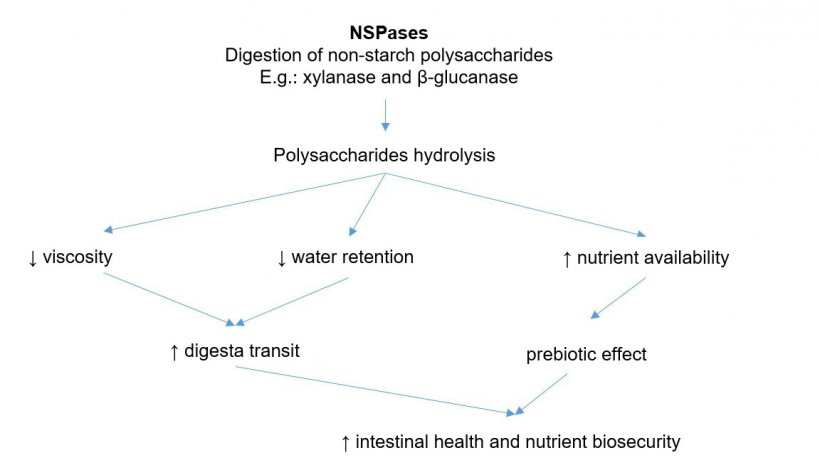

One of the strategies to influence in this aspect are the prebiotics. The concept of prebiotics started when it was observed that inulin and fructooligosaccharides (FOS) stimulated bifidobacteria, which are considered good for intestinal health (Gibson and Roberfroid, 1995). Nowadays there is a lot of literature in pigs that supports the use of prebiotics to select Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp., Bacteroides spp., etc. This ability to influence the microbiota is also attributed to the inclusion of a certain level of fermentable fiber in the diet, in order to stimulate the colonic fermentation (Correa-Matos, 2003); the reduction of protein levels in the diet, to avoid hind-gut protein fermentation (Pérez, 2013); and to the inclusion of exogenous enzymes, which produce oligosaccharides with prebiotic effect from non-starch polysaccharides (Bedford, 2004).

In turn, you can also plan a probiotic treatment with the aim of modifying the nutrients present in the intestine. To begin with, a strategy to reduce specific nutrients and compromise the growth of pathogenic bacteria can be designed, promoting a more favorable population for our pigs. This objective is achieved through the use of probiotic bacteria that competes for these nutrients, and uses them more efficiently (Gerritsen et al., 2011). On the other hand, other probiotic strategies are based on cross-feeding, which consists of providing a probiotic that provides specific metabolic products to promote the most interesting bacteria. An example of this practice would be the study by Belenguer et al. (2006), where the production of lactate and acetate by bifidobacteria stimulated the growth of other butyrogenic bacteria (providing energy for the colonocytes).

Causing changes in the environment

Changes in the fermentative environment and pH also will influence the microbiota profile. This can be achieved directly with acidifiers or indirectly with probiotics, for example, with lactic acid bacteria, which produce lactic acid as a major metabolite (Yang et al., 2015). The fermentation of prebiotics such as FOS or inulin also results in a production of organic acids, which reduce the intestinal pH and prevent colonization by enterobacteria or clostridia sensitive to this acidic pH.

Interfiriendo en la comunicación bacteriana (Quorum Sensing)

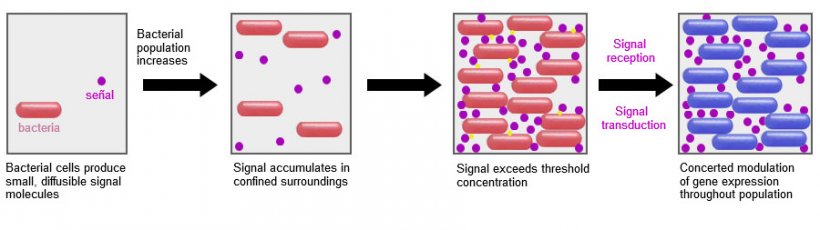

A very promising line of research is to interfere in the Quorum Sensing (QS), the communication mechanism between bacteria. This communication takes place through signaling molecules and allows them to create a coordinated response, activating or deactivating the expression of certain genes and eventually enabling them to act as a collective, providing survival benefits such as the formation of biofilm or sporulation (Hughes and Sperandio, 2008). Through the use of specific probiotics, which release other signaling molecules, or alternatively, enzymes that hydrolyze the signaling molecules present, we can influence these QS channels (Brown, 2011). However, it must be mentioned that much of the information that we currently have available on bacterial communication is at an in-vitro level, and it will be interesting to see if the results of in-vivo tests are consistent or depend on the gastrointestinal environment of the animal.

Modifying patterns of colonization and development of the gastrointestinal tract

Finally, it is worth pointing out that, the first weeks of life, is the stage where all these strategies will be potentially much more effective and longer lasting. On the one hand, it has been described that the neonatal microbiota is relatively dynamic and much influenced by the environment and the maternal microbiota. On the other hand, the microbial composition in this stage is determinant for the future, a fact known as "microbial imprinting" (Konstantinov et al., 2006). Moreover, it is also known that the microbiota plays an essential role in the education of the immature gastrointestinal tract, to generate functionally efficient systems when the animal is an adult (Lewis et al., 2012). This is evident in studies with germ-free animals, where it has been described that animals without a microbiota have a sub-developed immune system and intestinal architecture (Luczynski et al., 2016). Likewise, it has also been demonstrated in farm studies, where animals exposed to greater microbial diversity have been associated to a healthier microbial profile, adaptable to environmental changes and more resistant to potentially dangerous bacteria (Mulder et al., 2009). In conclusion, from a practical point of view, the neonatal stage, and even sows, can be the most efficient time to influence the microbiota, establishing more robust and lasting benefits (Kenny et al., 2011).