PRRSV continues to evolve, creating clusters of different strains over time and geographical space. The most recent ‘highly pathogenic’ PRRSV strain affecting the U.S. has an RFLP pattern 1-4-4 and it is a particular variant within the Lineage 1 C (hereon referred to as L1Cv).

Important questions are where are these viruses coming from? How do they quickly disseminate in the swine industry? Understanding those allows us to move to the next logical question: ‘how do we stop this cycle?’

The Swine Disease Reporting System has repeatedly demonstrated that positivity of PRRSV PCR samples coming from grow-finish sites is 20 to 30 percentage points higher than that of samples from sow farms (Figure 1). Also, the SDRS data reports that the seasonal spikes in positivity of grow-finish PRRSV PCRs precede those from sow farm samples (this phenomenon is also seen for enteric coronaviruses and Influenza A virus detection).

At first glance, this seems counterintuitive, as most pigs flow from sow farms to grow-finish and not vice-versa. Why do we see a higher positivity in grow-finish, and why is there an uptick in PRRSV detection in grow-finish pigs before sow farms? Part of the reason is that many sow farms are routinely monitored to confirm status or progress towards control, so it is not surprising that many samples are PCR-negative. However, growing pig monitoring is by far motivated by clinical expression of disease. Magalhaes et al (2021) reported that submission of samples for diagnostic testing is associated with increased cumulative mortality of grow-finish. In other words, growing pig groups dealing with respiratory disease (i.e., PRRSV-infected) are more likely to submit samples for testing, influencing the data to represent PRRSV activity in affected flows (not the general population).

More importantly, it is well known that the biosecurity level of grow-finish populations is (still) subpar compared to sow herds. For instance, it is not common to see enforcement of shower in-shower out, same day-shared labor among sites happens frequently, and trailer decontamination after every load is also not common. Also, not all growing pig populations are adequately immunized against PRRSV. Altogether, these factors create great opportunities for virus circulation, emergence, and transmission among grow-finish sites, increasing the overall pressure of infection in the area and between sites with operational connections (e.g. sharing employees, supplies, trucks). The high ‘load’ of PRRSV (and other pathogens) in the field translates to exposure and outbreak of sow farms, keeping the transmission cycle constantly active.

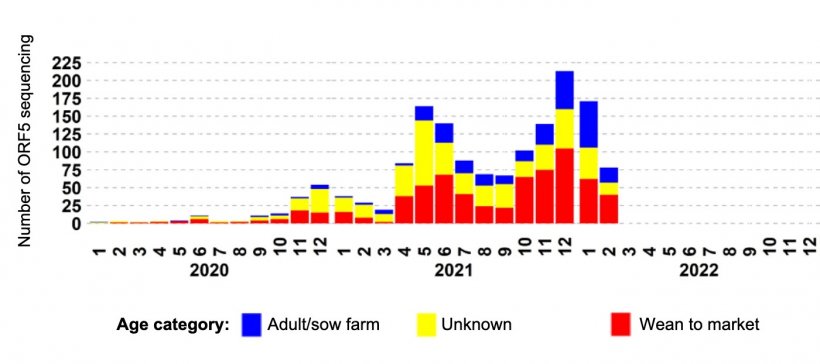

Going back to the L1Cv example, the epidemiologic curve summarized with data from U.S. veterinary diagnostic laboratories demonstrates 3 waves of detection, where the first wave was mainly driven by detection in grow-finish pigs. The second wave had a higher participation of sow farms, but it was not until the third wave that L1Cv activity was reported in a great number of sow farms (Figure 2).

Where do we go from here?

So far, we stressed the importance of grow-finish populations as important sources of PRRSV, new and old. The large population relative to sow farms, the lack of sterilizing immunity to the virus, and the high number of connections among sites makes the grow-finish population a hot spot for virus activity, generating new copies of virus that will continue to find new sites to get infected. So, where do we go from here? What can the industry do to influence this chain of events?

Short answer = biosecurity and biocontainment.

We believe it is time for the industry to step up and raise the biosecurity and biocontainment bar for grow-finish pigs, similar to what has been done and it is still happening in sow farms. It is hard to imagine a swine industry with less pig movement than we have today, but there are a few strategies that can significantly help decrease viral activity.

It is beyond the scope of this article to prescribe specific biosecurity guidelines. However, we believe in the importance of messaging the importance of biosecurity amongst grow-finish personnel. People tend to better comply with activities and procedures that they understand the importance of. Before creating new biosecurity rules, we need to go back to the basics and implement those practices we know work (e.g., shower or change of clothes).

Other ‘low hanging fruit’ to reduce the pressure of infection in grow-finish is to better take advantage of immunization tools. It is well documented that vaccination programs significantly reduce shed and spread of wild-type PRRSV in pig populations of all ages. Production systems and veterinary clinics should work with pharmaceutical companies, with help from academic institutions, to demonstrate the economic advantage of such practices in regional coordinated programs. One great recent example is the success case of Hungary to eliminate the wild-type virus from the country, largely done by diagnostic testing and immunization. The Netherlands and Danish industries are currently evaluating national control / elimination programs along those lines.

Back to production systems and veterinary clinics, we are confident you wish to reduce the number of outbreaks and reduce the PRRSV genetic diversity (# wild type strains) circulating in your herds. One question to reflect on is ‘what can you do in your system or region to reduce the pressure of wild-type PRRSV infection in growing pigs’? Whatever your ideas are, we are here to help. Do not wait until tomorrow!