Ammonia (NH3) emissions from the agricultural industry in the European Union (EU) in 2020 totaled 3.2 Mt, representing 96.6% of total ammonia emissions, of which 67% are estimated to be due to livestock manure management, a slight decrease of 5% compared to 2008. While total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the EU fell by 27% during the period 2008-2020, those corresponding to the agricultural sector have remained almost unchanged at around 465 Mt of CO2 eq/year, representing 16.9% of total emissions in 2020, with methane (CH4) responsible for 44.5% of these emissions. There is an urgent need to reduce these emissions in order to combat global warming and its effects.

Total and ammoniacal nitrogen in slurry is relatively easy to measure and therefore so is estimating the volume to apply to a plot according to the crop needs and to comply with the European Nitrate Directive. On the other hand, nitrogen in the form of ammonia (NH3) or nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) is not so easy to measure, they are like invisible enemies before our eyes.

They are enemies because animals breathe these gases and are affected if manure is stored in pits under slats; because the volatilized nitrogen reduces the fertilizer and economic value of slurry; because CH4 emissions reduce the potential to produce biogas for energy and economic purposes; and because these gases have negative environmental effects, producing acid rain in the case of NH3 and nitrogen oxides, and have a greenhouse effect, about 25 times more than CO2 for CH4 and 298 times more for N2O. Preventing NH3, N2O, and CH4 emissions must be included in the objectives of improving livestock manure management.

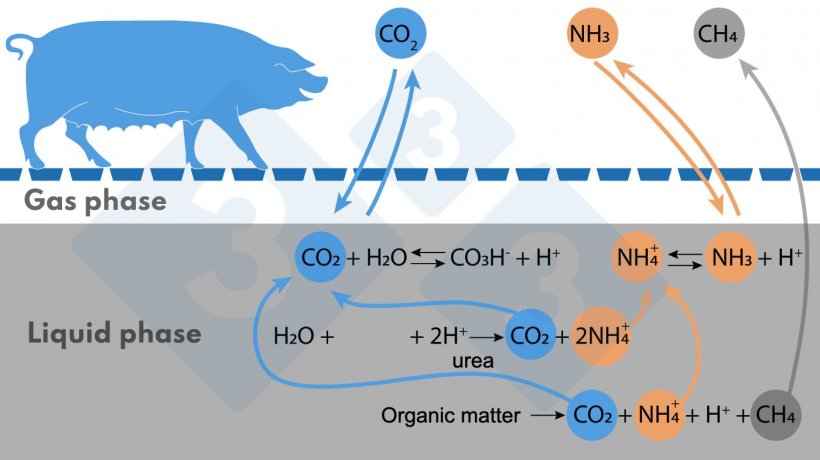

Figure 1. Simplified diagram of reactions affecting NH3 and CH4 emissions.

The main source of ammoniacal nitrogen is urea, followed by the anaerobic decomposition of protein-containing organic matter. Ammoniacal nitrogen is found in the liquid medium in the ionized form (NH4+) and in the form of NH3. The NH4+/NH3 equilibrium depends on pH and temperature; with increasing temperature or pH the equilibrium shifts to the right (as indicated in Figure), forming more NH3, which is volatile.

The origin of CH4 is the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter. The more digestible volatile solids (VS) the organic matter in the slurry contains, the more CH4 can be produced.

A third gas emitted is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is not counted as a greenhouse gas because it is of biogenic origin. In the liquid medium, this gas is in equilibrium with bicarbonate (CO3H-), which regulates the pH of the medium. When the protons (H+) involved in the above reactions accumulate, the pH could drop, but in this case the CO2/CO3H- equilibrium shifts to the left and CO2 is emitted, which helps to maintain the pH around neutral or slightly higher. This negatively affects acid consumption if you want to acidify the slurry to avoid NH3 emissions.

Direct N2O emissions occur as a result of oxidation reactions of ammonium to nitrites or nitrates, or reduction of these to N2 gas. These reactions can occur in a controlled manner in biological NDN (nitrification-denitrification) systems or in an uncontrolled manner on rough surfaces exposed to the atmosphere (naturally crusted lagoons, separated solid fraction piles, etc.). Of the NH3 that volatilizes, 1% is considered to be oxidized to N2O in the atmosphere (indirect emissions).