The -not so new- challenges when talking about PRRS virus

It is not news that porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) has important features that contribute to constant disease re-emergence in swine herds which leads to considerable animal health issues and economic losses. One of these features is its rapid capacity to mutate and potentially become more severe and/or even infect animals previously “immune” to a different PRRSV variant. For this reason, in order to understand a PRRSV “type” present in a farm – whether that is a virus from a new outbreak or a “resident” virus- it became very common to analyze the PRRSV genome.

This task is usually done by sequencing an important part of PRRSV called the ORF5 gene; to understand where the virus fits evolutionarily and how it compares to previous virus that were detected in the site or in the neighborhood/ region.

PRRSV sequencing information has been widely used in the field to:

- understand which virus is causing problems

- for guidance on outbreak source

- for differentiation between vaccine strains and “residing”/ newly introduced strains

- for vaccine choices, etc.

Recently, the “lineage” classification has been increasingly used to classify viruses. This method was developed around 2010 (Shi et al., 2010), when PRRSV were divided into 9 distinct lineages; and further refined when PRRSV was further subdivided into sub lineages.

The elephant in the room: is sequencing one sample good enough?

PRRS sequencing is usually not cheap, therefore it is more commonly done under “special situations” and not routinely (e.g. during new outbreaks, after virus inoculation events, etc.). In addition, during these cases, only one sample or a pool of samples (out of many commonly taken on-farm) is used for sequencing in the vast majority of diagnostic cases.

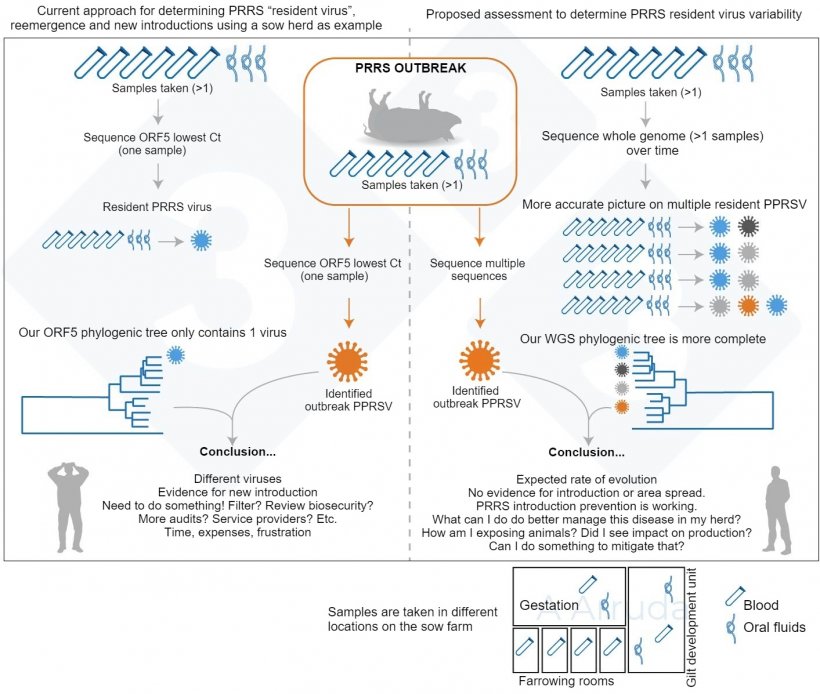

The implication is that, in many cases, veterinarians, producers, and other animal health personnel commonly use a single sequence information to make important conclusions regarding virus source (especially for new outbreaks), guide outbreak investigations, and to inform future interventions.

In our study, we wanted to confirm that, if we sequenced multiple samples taken within the same day, all samples would yield the same sequence, or sequences that would be “close enough” to be considered at least the same virus lineage. We also wanted to attempt whole-genome sequencing (WGS) along with ORF5 sequencing to see whether we would gather more information. WGS could have an advantage since it gives information on the whole virus, while ORF5 has been historically used but only tells us a piece of the story. However, since it is still a relatively recent development and can be expensive (in the United States it costs approximately three times more than the ORF5 sequencing), we are still learning how to interpret it and our “database” for comparison is much smaller compared to ORF5.

We suspected that, given the rapid mutation rate of PRRS and the large size of modern swine facilities, we could find multiple lineages of PRRS within a sampling event, which would be concerning. A graphical summary of our study rationale is in Fig. 1.

Studying how many PRRS strains can we find on our farms

We enrolled five farms in the study, 3 breeding herds and 2 grow-finish; and sampled monthly for approximately one year using different types of samples (tonsil scrapings, oral fluids, processing fluids). We always sampled the same locations in the barn that were spatially spread out throughout the facilities to try and get the most representation possible of the whole site. We had up to 16 samples per site every month, and all of them were tested using quantitative PCR; and following this, the positive samples were ORF5 sequenced.

What did we find out?

Our most important finding was that under field conditions, we were able to detect up to three different PRRSV lineages during a single sampling event for breeding herds, and up to two for growing pig herds. This is shown on Fig. 2.

Figure 2. PRRSV sub-lineages encountered in study farms (1-5) throughout the duration of our sampling events (in months) for the different sample types.

| Sampling event | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm | Sample type | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 1 | Processing fluid | L1H | L1H | ||||||||||

| Tonsil scraping | |||||||||||||

| 2 | Processing fluid | L1H | L1H | L1A | L1H | L1H | |||||||

| L1H | |||||||||||||

| L8† | |||||||||||||

| Tonsil scraping | L1H | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Processing fluid | L1H | L1H | L1H | L1H | ||||||||

| Tonsil scraping | |||||||||||||

| 4 | Oral fluid | L5† | L1A | ||||||||||

| L5† | |||||||||||||

| Tonsil scraping | L1A | L5† | L5† | L1A | |||||||||

| L5† | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Oral fluid | L1A | L1A | L5† | |||||||||

| Tonsil scraping | L1A | L1A | |||||||||||

We also noted that, in the case of our study, oral fluid samples were very difficult to sequence, while processing fluids were the easiest. Considering both are “composite” samples, that could potentially be explained by overall higher Ct values, indicating less viral amounts for oral fluids compared to processing fluids. We tried to attempt WGS but finally, we were unable to obtain full whole-genome sequences from any of our samples. We suspect that could be due to the types of samples we utilized, but further research is needed on this topic.

These findings show how important it is to consider sequencing several samples when making important decisions, even though we understand this will come with higher costs.

Acknowledgments

The National Pork Board provided funding for this project. We would like to thank veterinarians and producers who were instrumental for sample collection.