The answer is not that simple, ELISA and PCR results are not 100% conclusive, so certain management practices discussed here must be put into place in order to provide additional protection.

A few years have passed since PRRS first reached our farms. By trying different control strategies we have found that control is not achieved exclusively by use of vaccines. Rather, we must use management practices that prevent the perpetuation of the virus on any areas of the farm; avoiding virus reintroduction in gestation which would cause reproductive problems, and produce viremic piglets that would later cause problems in the growing phases. One management area that has received the most attention, due to its importance in maintaining gestation stability, is the introduction of replacement gilts.

When replacements come from an external source, introducing PRRS-negative animals assures that a new strain of the virus won't enter the farm and disrupt health stability, but at the same time, it poses the challenge of following an adequate acclimation program. When a stable farm raises its own replacements the risk is that, over time, it will become negative, which would increase the risk of instability reoccurring. The solution to these problems is to design and implement an acclimation program which, either by contact with the virus circulating on the farm, or by the use of vaccines (or a combination of both), will ensure that gilts develop immunity to the disease and overcome the shedding status after contact with the virus. Thus, introducing gilts into the gestation or breeding area of the farm will not pose any risk to maintaining stability. But when these strategies are used, there are always some doubts: Are the replacement animals I'm bringing in really protected? Are we sure they have stopped shedding the virus by the time they contact the rest of the sows?

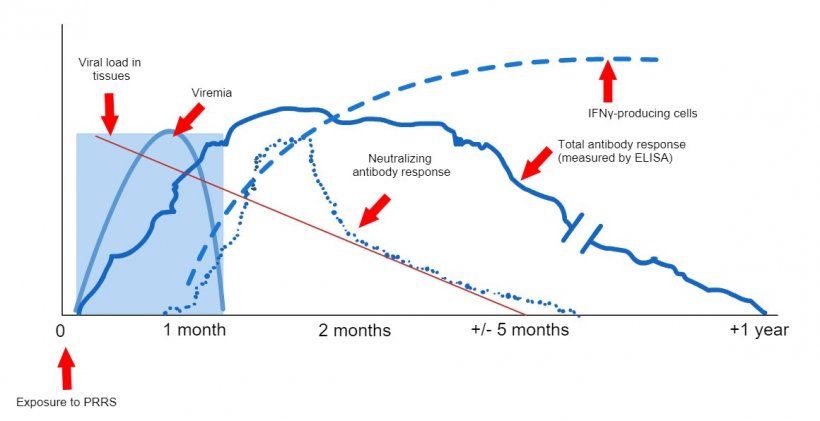

The techniques available at field level, to indicate the production of antibodies (ELISA techniques) do not allow to correlate the results provided with the level of protection (López, 2007), they only indicate that contact has been made with the virus. At the experimental level, there are other techniques that allow us to know if cellular immunity has been developed and still others that allow us to know if the animals have the capacity to seroneutralize the virus, both results telling us more about the real level of protection. But unfortunately, these techniques are expensive and complex, which is why they are not commonly used. The ELISA techniques have the added problem that, given the sensitivity of the technique, we can find a (small) percentage of animals that despite having contacted the virus give a negative result (false negatives). Therefore, in practice, what we will do is perform a serology using an ELISA test on a significant percentage of gilts. We are looking to see that the group is positive, which will be considered positive, even with some negative results (as long as it is within the sensitivity limits of the test carried out).

Graphic 1: Immune system response of a sow infected by PRRS virus (López and Osorio, 2004).

Ensuring that sows no longer shed the virus seems easier, considering that today we have PCR techniques that allow us to detect very small amounts of viral particles. However, in the case of animals infected by the PRRS virus, viraemia or the presence of the virus in blood will not last more than 4-6 weeks in most cases; but we know that animals without the virus in the blood can be carriers of the virus at a tonsillar level for much longer periods (Horter, et al. 2001). In order to know if the virus is present in the tonsils, we must perform a biopsy of the tonsils, which is not practical. This is the reason why, despite its limitation, we continue to use PCR as a technique to approximate the carrier status. These PCR can be performed from blood or oral fluid samples and, always, on a significant percentage of the population that we are going to introduce.

In practice, we want to have the replacement animals be ELISA positive and PCR negative before putting them in contact with the rest of the sows. But, considering the limitations of the techniques, we must provide extra security through good management; meaning, having a sufficiently long acclimation period (about 12 weeks) to ensure contact and that shedding stops, and separate management of the gilts, at least during the first third of gestation, in order to buffer the possible presence of a gilt shedding virus within the group.