To establish an accurate disease diagnosis is compulsory to counteract a given clinical problem in any animal species. In all cases, the clinical examination of the patient/s is the corner stone for further developments in terms of diagnosis approach.

Sudden disease outbreaks represent significant challenges for both farmers and veterinarians, who must identify and counteract the causes of the problem to restore normality. Under these circumstances, the swine veterinarian becomes an investigator, since he/she must assess multiple elements that may contribute to disease causality in a complex scenario involving aspects related with environment, nutrition, biosecurity, epidemiology, presence of multiple pathogens and human-pig interaction.

Population-wide diseases tend to be of infectious or nutritional (toxicities or deficiencies) origin. The first diagnostic approach always includes thorough clinical and epidemiological investigations by the veterinarian. If the clinical outcome implies mortality or severely affected pigs, necropsy of some of them (those considered representative of the condition) should provide some clues about the cause, or at least allow ruling out certain aetiologies.

Necropsy should be performed in an orderly manner, with a systematic approach and being complete.

Presence of lesions might not provide specific causes in most cases but allows orientation about them or narrowing down the differential diagnostic list

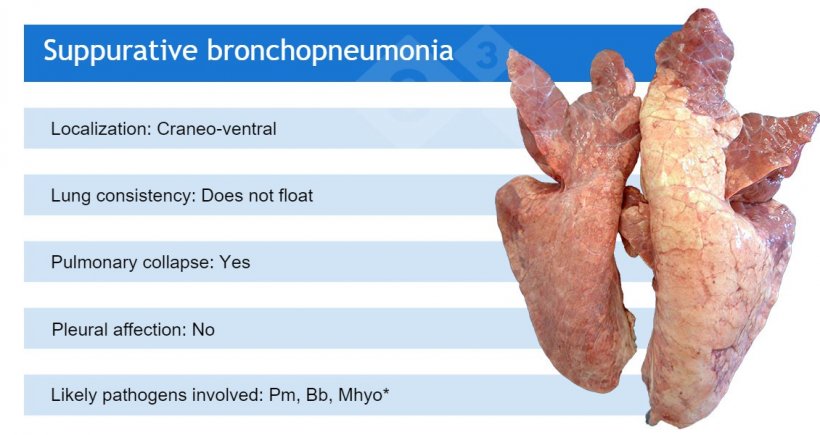

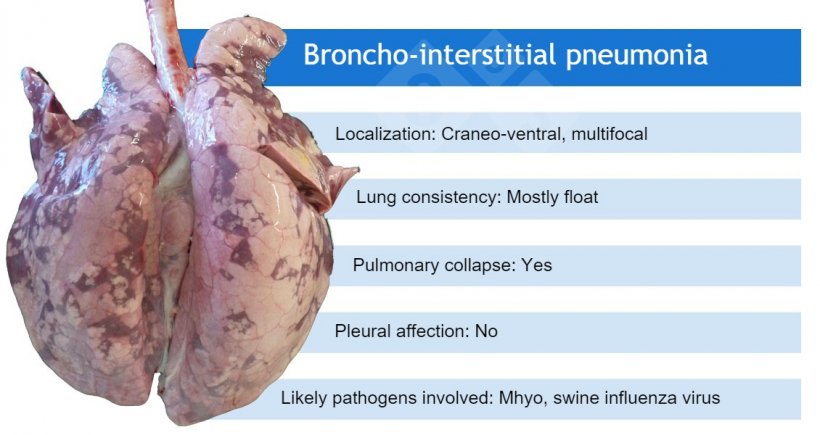

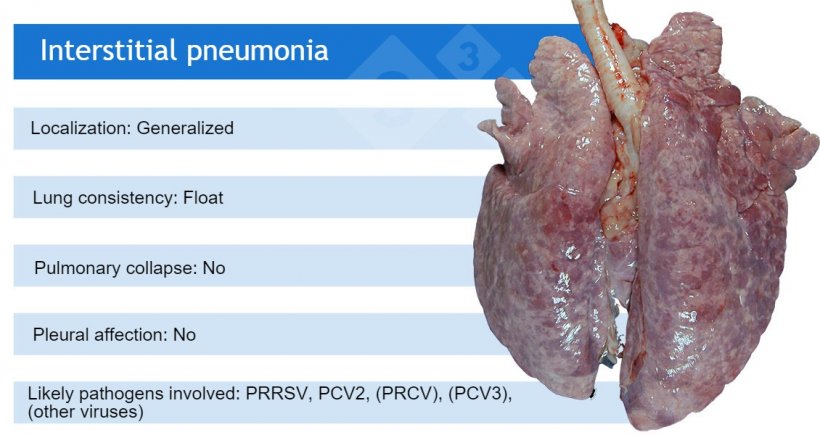

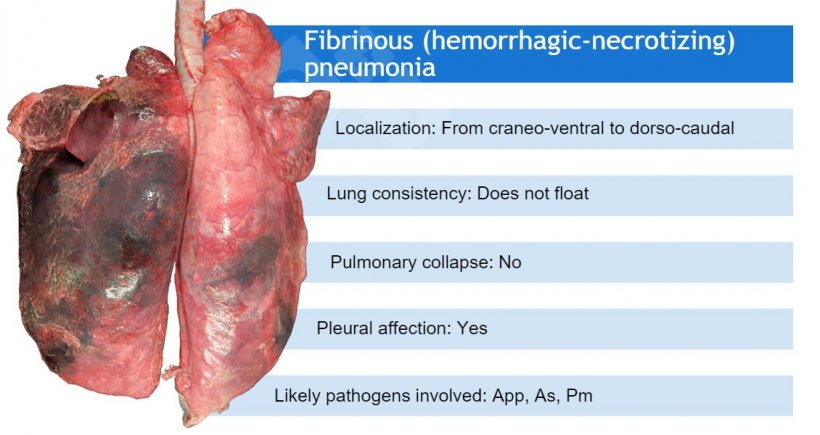

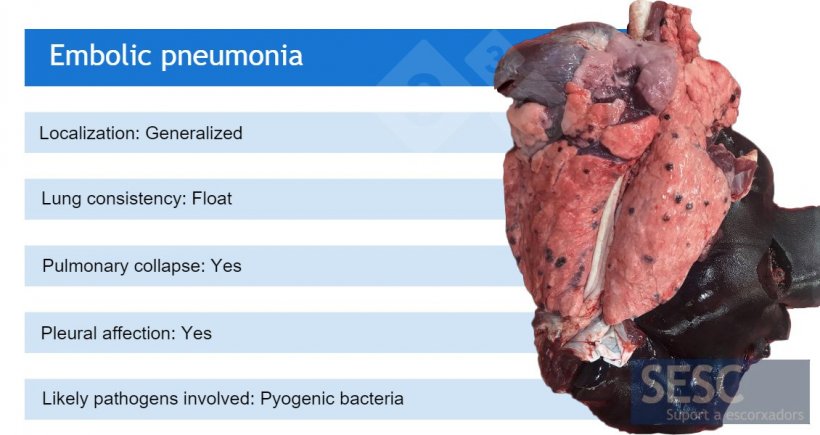

As an example, gross pneumonia patterns offer a set of aetiological possibilities, although in several cases it is needed to go beyond and use additional (laboratory) tests.

*Mhyo usually participates in suppurative bronchopneumonias as an initiator pathogen (causing first a broncho-interstitial pneumonia).

PRCV, PCV3 and other viruses such as adenoviruses, Aujeszky’s disease virus and others, usually cause mild interstitial pneumonias.

Laboratory analyses: all that glitters is not gold!

Different analytical approaches help identify potential pathogens (viruses, bacteria, parasites, fungi) or toxins involved in a clinical problem. The most frequently used nowadays involve molecular biology tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its variations (qualitative, quantitative, for DNA or RNA). The big advantage of this technique is its sensitivity (able to detect minimal amounts of pathogen genome or gen codifying for a toxin), but this is also its drawback, since the mere detection of a pathogen or toxin in an endemic scenario is not enough to establish an unequivocal etiological diagnostic.

Other laboratory techniques such as bacterial isolation (including antibiogram) are extremely useful, since allow establishing an etiological diagnostic and offer a putative successful treatment. Antibody detection techniques, on the other hand, are excellent monitoring tools, but offer poor diagnostic possibilities since presence of such antibodies depends on vaccination and/or infection status as well as maternally derived immunity.

Histopathology: an added value tool to provide consistency to the diagnostic investigation

Apart from those laboratory tests specifically focused on the determination of pathogens or toxins, histopathology can provide a strong framework to establish the real causality of a clinical problem. Said in other words, detection of a particular pathogen or toxin must be consistent with the clinical, epidemiological and gross lesion observations, and histopathological analyses can definitively support such consistency.

A good example of microscopic assessment usefulness would be the detection of a virus by PCR in a respiratory problem in which the typical histological lesions caused by this agent are not present in the lung (assuming the pig or group of pigs are representative of the observed disease). Such scenario should prompt to recapitulate on the suspected diagnosis and investigate further.

The swine veterinarian should consider histopathology as a very valuable tool, at least as important as PCRs, bacterial isolation or antibody detection techniques. Microscopic analyses allow morphological diagnoses that reinforce or contradict what has been established by means of clinical, epidemiological or other laboratory results, therefore contributing to establish the likely etiopathogenesis of the clinical problem. This overall information is important, since is a kind of predictor on how the control and prevention measures implemented to counteract the disease may work or not.

Sample collection for histopathology (and for other laboratory tests) is relatively easy but demands certain disease pathogenesis knowledge as well as some technical skills:

- Specimens must be collected from fresh carcasses (ideally recently dead or euthanized pigs).

- Tissues be immediately fixed by immersion in 10% buffered formalin.

- Submission of refrigerated samples for histopathological analyses is not recommended, since certain degree of autolysis occur.

- Also, frozen samples imply multiple artifacts that jeopardizes microscopic interpretation.

- Tissue sample size must be relatively small (or at least thin to favour fixation).

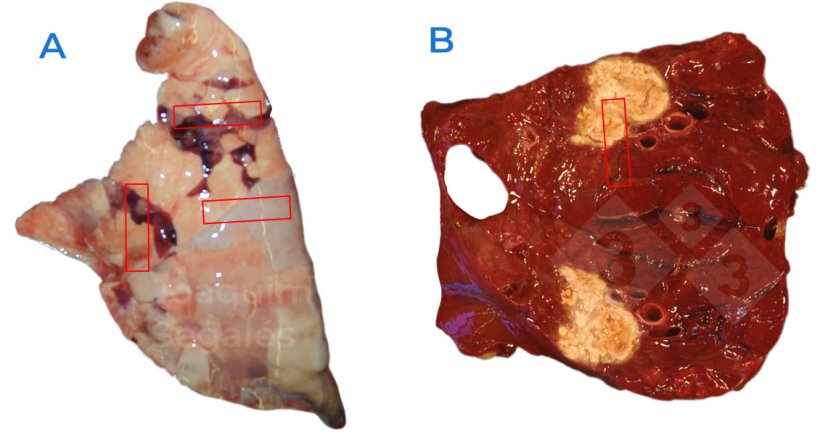

- Samples should include grossly affected portions as well as pieces of presumably normal tissue (Figure 1).

- In case of intestine samples, it is important to longitudinally open the intestine to ensure that formalin is in direct contact with the enteric mucosa.

- In contrast, a big organ such the brain is preferred being fixated entire or one half; the reason for this procedure is to ensure that brain topography is maintained during fixation, and then the pathologist can select the right portion to try to establish the most likely diagnosis.

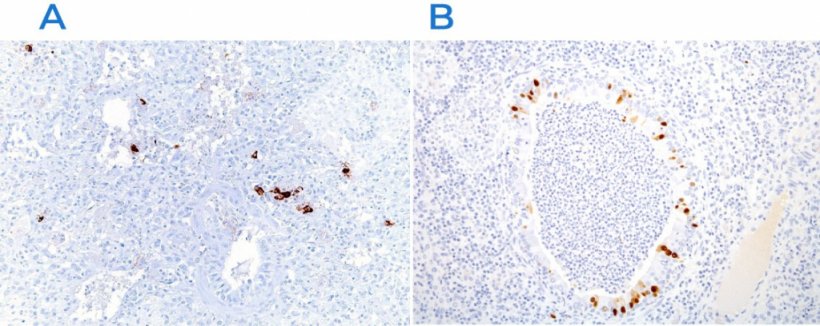

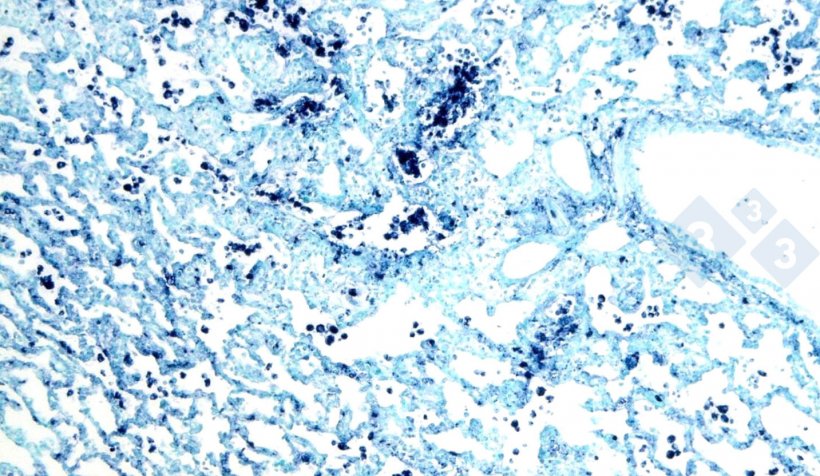

Importantly, besides the plain histopathological analysis (based on the haematoxylin and eosin stain, Figure 2), other pathological additional tests may help in seeking for etiological agents.

The most used ones are immunohistochemistry (Figure 3) and in situ hybridization (Figure 4), which allow detecting pathogens at the site of action, supporting their role in the clinical and pathological context. Besides, there are other techniques (histochemical stains), which are not sufficient to establish a specific aetiology, but able to give indications about the cause (e.g., Groccot stain to detect fungi or Gram stain to detect gram-positive or -negative bacteria).

In summary, the swine veterinarian, besides his/her own clinical, epidemiological and gross lesion investigations, has a variety of analytical possibilities, in which histopathology can play a vertebral role. Effective communication between clinicians and pathologists enhances diagnostic capabilities, leading to earlier and more efficient resolution of clinical problems.