In the event of an ASF outbreak, an epidemiological investigation must be carried out in a timely manner to identify the possible source of virus entry and to estimate the High Risk Period (HRP), i.e. the likely length of time that ASF has been present on the farm. It is very important to detect infected farms as early as possible after virus introduction to:

- prevent further spread

- minimize losses in the pig sector

- reduce government costs associated with disease eradication.

A reasonably accurate estimate of the HRP allows veterinary authorities to efficiently track secondary outbreaks or the spread of the virus via animal movements, contaminated products, vehicles, people and other means.

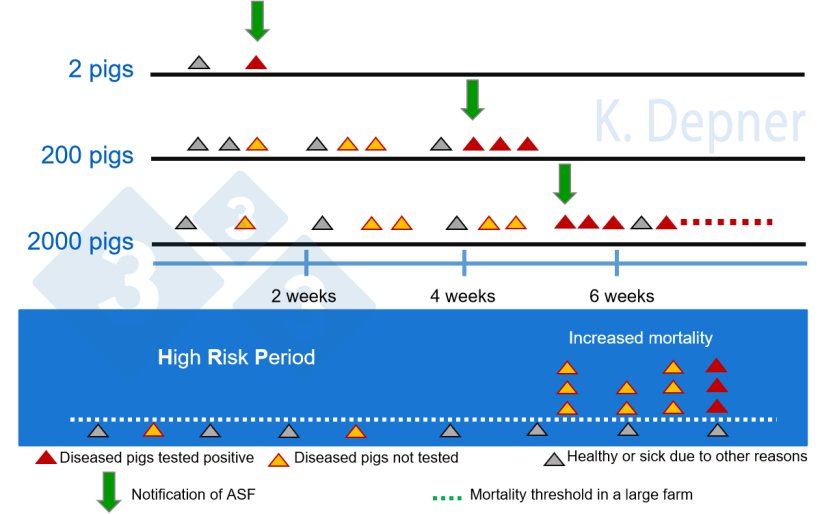

Imagine the following two scenarios: A small farmer with two pigs finds one of his animals dead when he enters his barn in the morning. The mortality rate in this case is 50%, and it is impossible to miss. On a large farm with thousands of pigs, two pigs die from ASF. Mortality is not yet alarmingly high and the incident would possibly be ignored without further notice.

Backyard holdings are generally in favor for early detection of ASF due to their small size and small number of animals, as sick and dead animals are usually detected relatively early during an outbreak. On large commercial farms, ASF virus may circulate for several weeks before a significant increase in mortality occurs and the disease is suspected and reported.

On large farms, the first animals to become ill and die from ASF may be missed unless there is an appropriate passive surveillance system that targets dead and diseased animals.

Animal experiments and field observations have shown that low to moderate transmissibility of ASF virus between pigs results in slow spread of the disease within a farm, especially in the early stages of the outbreak. The slow spread is mainly related to the relatively low contagiousness of ASF virus. Under unfavorable circumstances, the HRP can be several weeks or even months, during which the virus can spread unnoticed within different housing units or to other farms.

The main strategic objective of ASF surveillance in domestic pigs, especially in areas at risk, e.g. due to ASF in wild pig populations, is to keep HRP as short as possible by detecting infected holdings at an early stage. To ensure early detection, regular sampling and examination of sick and dead pigs is unavoidable. Each week, at least the first two deaths, including post weaning pigs or pigs older than two months in each production unit should be tested for ASF virus (e.g. with a PCR test). This approach of enhanced passive surveillance is based on the assumption that due to the high case fatality rate of ASF (>90%), almost all infected pigs will become sick and die. Therefore, any sick or dead animal would be a good candidate for ASF testing. Effectively conducted enhanced passive surveillance as an early detection measure can lead to a significant reduction in HRP.

If PCR-positive pigs are diagnosed, it makes sense to also test for antibodies against ASF. If ASF antibodies are also detected, this is a clear indication that the virus must have been on the farm for longer than ten days. As a rule, the antibodies detectable in the ELISA test are found in animals that do not die within the first 10 days after infection.

In addition to laboratory results, mortality and morbidity data are also useful indicators for estimating HRP. For example, mortality curves can provide an indication of when the first animals may have died due to ASF. However, under field conditions, estimating HRP is quite difficult and often unsatisfactory due to insufficient or questionable data. The history based on clinical signs and morbidity records might not always be reliable or relevant laboratory examinations might be missing.

With early detection of the disease and thus a short HRP, it can be assumed that large parts of the farm are not yet affected by ASF. Assuming a slow virus spread, unaffected farm units could be exempted from culling if reliable biosecurity and surveillance management is in place and the legal situation allows it. Good farm management and strict internal biosecurity measures, as well as an intelligent surveillance system, should be in place to maintain and demonstrate freedom from infection in the unaffected units of the remaining pig herd.