The real case discussed here happened in an 800 sow farm in the middle of the process of increasing their census up to 1150 productive sows by highly increasing their replacement rate for a year. They work with 3-week batch farrowing system and they are planning to transition to a 1 week system when the census reaches 1000 sows. Historically, the farm global return rate is around their target of 10%. Most of these returns are regular, and the second most frequent are the late returns (gestation losses at the gestation pens).

The occurrence of significant percentages of irregular returns is limited to periods of PRRS instability.

First phase. PRRS recirculation

During the second quarter of 2017, irregular and late returns increased, as well as premature farrowings. The episode is similar to others experienced in previous occasions, when there was a PRRS recirculation. In addition, due to the current census increase, the percentage of gilts in the farm is higher, which increases the risk. These gilts are subjected to a minimum quarantine of 90 days in an isolated unit independent from the rest of the farm, They are immunized with a commercial live vaccine and their oral fluids are always tested before transferring them to the gestation unit; if they test positive to PCR, the gilts are retained until the results of the test come back negative.

Despite all these immunization and control measures and a relatively good internal biosecurity, veterinarians were aware that the risk of recirculation during the census increase was higher.

Given the occurrence of the aforementioned irregular returns and the odd abortion, samples were taken that confirmed, as was expected, PRRS recirculation. All common measures were taken, quickly controlling the situation.

Second phase. Reoccurrence of irregular returns

The farm stabilizes for just over a month, then there is a new onset of irregular returns. PRRS is immediately blamed for these new problems. Since they are faced with "the usual", the veterinarians do not even take samples on this occasion, and standard control measures are implemented straight away.

One month after the onset of the irregular returns, and in spite of implementation of the classical recirculation control measures, no improvement is seen. Thus, a data analysis is carried out in a bid to seek guidance, since this "recirculation" is not responding to previous patterns.

Effectively, after the analysis of the preliminary data, it was verified that the number of late returns was much lower than during the PRRS episode of the previous quarter (Figure 1, in orange).

Figure 1. Type of returns during the troublesome periods.

| Returns | ||||||

| Total | Early | Regular 1 | Irregular | Regular 2 | Late | |

| Second quarter of 2017 | 116 | 6 | 38 | 28 | 3 | 41 |

| Third quarter of 2017 | 119 | 8 | 41 | 29 | 14 | 27 |

Based on this table, the decision is made to analyze in depth the irregular returns that remain exactly the same in the two quarters (Figure 1, in blue).

The analysis of the second quarter of 2017 (diagnosed as PRRS recirculation through laboratory testing) shows that most of the irregular returns occur in nulliparous (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of irregular returns. Second quarter of 2017. WTS1 = Weaning-to-first service interval.

However, when analyzing the pattern of irregular returns in the third quarter, it is now detected that the sows that return are NOT nulliparous, and that 67% of sows showing an irregular return on their first return had a weaning-to-first service (WTS1) interval greater than 8 days (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Distribution of irregular returns. Third quarter of 2017. WTS1 = Weaning-to-first service interval.

When this dramatic change of pattern was finally detected, samples were immediately taken; the results show that the PRRS virus is stable, so another cause is taken into consideration: the transition between a 3-week to a 1-week batch farrowing system.

As discussed at the beginning, the farm is increasing its census in a bid to exceed the 1000 productive sows, so a change from a 3-week to a 1-week batch system is implemented to facilitate management.

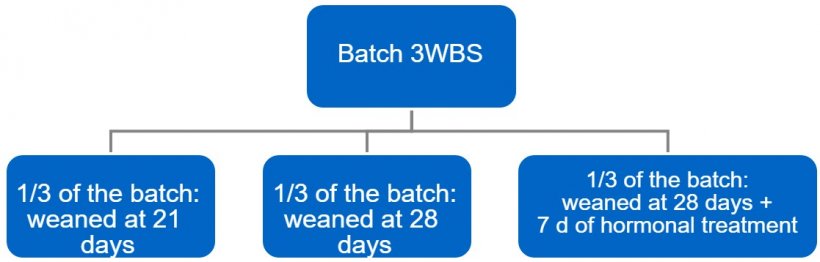

In order to do that, one third of the sows are being treated with hormones to delay the onset of estrous for one week, so that the farmer could distribute a batch of weaned sows through three weeks (Figure 4). The situation of these sows is assessed.

Figure 4. Transition process from a 3-week batch system (3WBS) to weekly batches.

As the group of Figures 5 show, sows with a WTS1 > 8 days account for exactly one third of the total sows weaned during this period of time. 87% of them were serviced on the dates matching these oestrus delayed with hormones due to the transition to weekly batches. Their return rate is more than doubled compared to the other group (WTS1 < 8 days) and 41% of them are irregular.

We can conclude that the origin of these irregular returns very likely lies in the hormonal treatments administered. The sows come on heat 5 days after weaning but they are not mated until 12 days, which would be the expected time with a correct hormonal treatment.

| WTS1 < 8 days | WTS1 > 8 days | |

| % of sows | 68 % | 32 % |

| Returns | 9.8 % | 19.4 % |

| Acyclic returns | 19 % | 41 % |

Figures 5. Breakdown of returns of sows transitioning to a weekly farrowing.

Irregular returns are usually associated with health problems, especially in farms infected with PRRS or influenza. However, the origin of a problem should never be taken for granted just because it is similar to others experienced previously.

Once again, a correct analysis of data helps the professionals in charge to find their way around the possible causes of the problems.