Introduction

The farm is a commercial 350 sow birth to bacon unit in Northern Ireland.

The unit is negative to Enzootic Pneumonia (Mycoplasma hyodysenteriae), Porcine Pleuropneumonia (Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae), Swine Influenza and PRRS (Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome).

The vaccination protocol operated is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Vaccination programme.

| Vaccine | Gilts | Sows | Boars | Piglets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parvovirus + Erysipelas + Leptospirosis | 2 ml injection at selection and 2 weeks pre-service | 2 ml injection 2 weeks before service | 2 ml injection twice a year | |

| Autogenous vaccine (Streptococcus suis & Staphylococcus hyicus) | 2 ml on day 65 after service and at day 95 after service | 2 ml at day 95 after service |

Gilts are homebred in the unit. Boars are used for teasing. Gilts and sows are served with Artificial Insemination from a single source.

The closest pig unit is 6 km away.

History

The farmer contacted the veterinary surgeon concerning an increase of respiratory distress and mortality in the finishing pigs during the previous 3 days.

Investigation

3.1. Clinical Investigation

During a farm visit in November 2017, there were many 18 to 24 weeks old pigs with clinical signs of coughing (Figure 1 & Videos 1 & 2) and cyanosis of the lower and distal parts of the body. The wet feeding trough was not emptied indicating loss of appetite. Rectal temperatures were taken from some animals clinically affected showing pyrexia. The body condition of the animals was normal.

Video 1. Clinically affected pigs coughing.

A second farm visit was done 2 weeks later to collect blood samples in the breeding herd and the growing/finishing pigs.

Mortality from weaning to finishing before the outbreak was 3.5%, mostly related to animals that had to be euthanised as a consequence of herniation and/or rectal prolapse.

3.2. Laboratory Investigations

Three dead pigs were post-mortemed on the farm in November 2017 (Figure 2).

There was multiple petechiation in the lung parenquima of all 3 post-mortemed pigs (Figure 3). Samples were collected and submitted to the laboratory for analyses.

The laboratory investigations of the lungs are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Laboratory results from the three sets of lungs submitted.

| Bacteriological findings | Biomolecular findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Lung 1 | No growth. | Negative to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae & PRRS by RT-PCR. Influenza Virus type A positive by RT-PCR (CT:18.1) Subtype H1N1. |

| Lung 2 | No growth. | Negative to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae & PRRS by RT-PCR. Influenza Virus type A positive by RT-PCR (CT:26.9) Subtype H1N1. |

| Lung 3 | No growth. | Negative to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae & PRRS by RT-PCR. Influenza Virus type A positive by RT-PCR (CT:31.5) Subtype H1N1. |

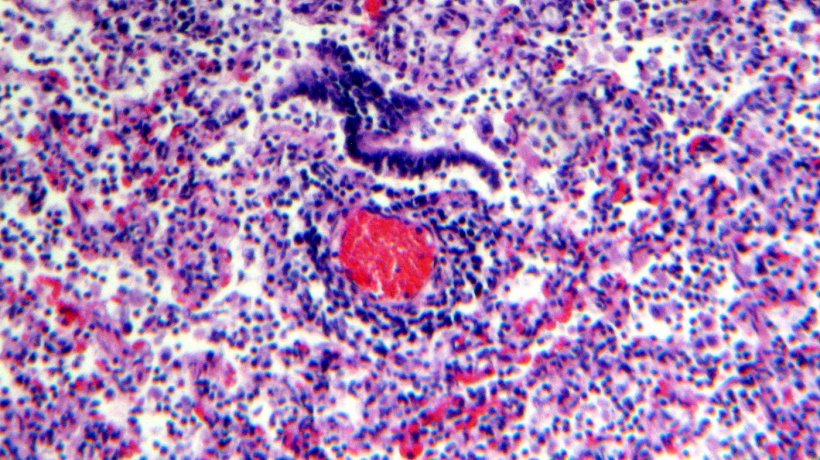

Histological examination of the lung tissue showed lymphocytic infiltration of the lamina propia and submucosa of the bronchi (Figures 4 & 5).

The laboratory investigations of the 14 blood samples collected from the breeding and finishing herd are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Laboratory results from the 14 blood samples collected.

| PRRS (ELISA) | Influenza A (ELISA) | Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (ELISA) | PCV-2 (ELISA) | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (ELISA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 x 12 weeks old blowing pigs | 3 (-) | 2 (+) 1 (-) |

3 (-) | 3 (-) | 3 (-) |

| 2 x recovered pigs | 2 (-) | 1 (+) 1 (-) |

2 (-) | 2 (-) | 2 (-) |

| 2 x coughing piglets from different sows | 2 (-) | 2 (+) | 2 (-) | 2 (-) | 2 (-) |

| 7 x sows | 7 (-) | 7 (+) | 7 (-) | 7 (-) | 7 (-) |

The positive Influenza A samples were tested for antibodies against subtypes H1N1, H3N2 & H1N2 and the pandemic subtypes panH1N1 and panH1N2. Very high antibody titres (≥ 320 to 2560) against all these subtypes were detected in the affected animals indicating a recent infection.

4. Differential diagnosis

Based on the clinical and laboratory investigations, a list of differential diagnosis was prepared as follows:

- PRRS (Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome).

- Influenza Virus type A (Flu).

- Enzootic Pneumonia (Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae).

- Porcine Pleuropneumonia (Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae).

A diagnosis of acute Influenza Virus type A was reached based on the history and consistent clinical and laboratory investigations.

5. Control programme

An emergency protocol for Flu was implemented in this unit, as follows:

- Mass vaccination of all the breeding herd twice with an interval of 3 weeks between injections.

- Pigs were vaccinated at weaning with 2 ml of a commercial Flu vaccine as soon as the viral infection was diagnosed.

- Medication of all the pig diets with 85 ppm of tylvalosin tartrate per tonne for 20 days in order to counteract respiratory pathogens.

Once the whole breeding herd has been immunised twice against Flu we implemented the following:

- Vaccinate gilts twice before service with an interval of 3 weeks between injections.

- The breeding herd received a booster shot 14 days prior to farrowing with one dose.

Unfortunately, at the time of the outbreak, the current Flu vaccines available in the country did not cover the pandemic subtypes panH1N1 and panH1N2. A Flu vaccine covering the pandemic subtypes has been introduced in the breeding herd since September 2018, as precaution.

6. Response to the control programme

There was an increase of mortality from 3.5% at the beginning of the outbreak to 11.5% at the peak 4 weeks later. Mortality gradually reduced to the normal level 10 weeks after the initial outbreak.

Conception rate dropped from 94% to 86% for two months. This was reflected with a reduction of the farrowing rate from 91% to 84% during the same period of time. There were no abortions.

7. Discussion

Swine influenza is an acute, infectious, respiratory disease of pigs caused by type A influenza viruses. The disease is characterised by sudden onset, coughing, dyspnea, fever and prostration, followed by a rapid recovery. Lesions generally develop rapidly in the respiratory tract and regress quickly, but in a few cases severe viral pneumonia may be followed by death (Easterday et al., 1999). All these clinical signs were detected during the clinical investigation of this case.

Swine influenza is caused by influenza A viruses, in the family Orthomyxoviridae. An enormous amount of information is available of the antigenic, genetic, structural, and biologic characteristics of influenza A viruses (Murphy et al., 1990; Lamb et al., 1996). The two surface glycoproteins of the virus, haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), are the most important antigens for inducing protective immunity in the host and, therefore, show the greatest variations.

Surveillance done in Northern Ireland from 2011 to 2013 showed that Pandemic H1N1 was the main subtype isolated in pigs followed by the other subtypes (H1N1, H3N2) in lower occurrence (Borobia et al., 2015).

Weather conditions were favourable for the spread of the virus at the time of this outbreak. It was humid with fluctuating temperature conditions for the previous 3 months and strong winds in the between. It is likely that humans or starlings (Figure 6) could have infected pigs by close contact or by airborne infection by the proximity to other pig units. Both options were likely to occur in this clinical case.

Morbidity in Swine Influenza is described to be high (near 100%) (Taylor, 1995; Easterday et al., 1999), as seen in this case. Taylor (1995) and Easterday et al., (1999) report a mortality rate less than 1% unless there are intercurrent infections and/or the pigs are very young. Unfortunately, in this case mortality was higher than 1%, as described earlier.

Reproductive, farrowing and neonatal problems with Swine Influenza have been described in the literature by different authors (Taylor, 1995; Muirhead et al., 1997; Easterday et al., 1999; Jackson et al., 2007) and were seen in this case with poor conception and farrowing rate only.

The use of tylvalosin tartrate in feed was based on reports from Dr. David Brown and Dr. Amanda Stuart in the Department of Pathology at the University of Cambridge. The effect of this macrolide antibiotic on PRRS reduced the number of cells infected in vitro compared with another macrolide antibiotic, tylosin. Tylvalosin also reduced the number of cells infected by several other viruses, including human and equine influenza viruses (Brown et al., 2006). Furthermore, tylvalosin has better intracellular accumulation and distribution for treating clinical disease than other macrolide molecules (Stuart et al., 2007).