Streptococcus suis (S. suis) is an endemic and zoonotic pathogen lacking non-antibiotic adequate prevention in nursery pigs. The pathogenesis is mainly associated with upper respiratory tract and tonsil colonization as entry to the circulatory system (Segura et al., 2016), although gastrointestinal infection cannot be discarded (Swildens, 2009). Colonization occurs at birth, during the nursery phase when pigs are mixed with other litters, and during outbreaks. Interestingly, outbreaks are frequently associated with co-infections and stress factors identified as potential triggers, but the natural infection process is not fully understood, and we lack a repeatable model that mimics the first steps of the disease.The disease is most recognized by neurological clinics associated to meningitis with mobility impairment and frequently mortality.

It is known from human and animal models that inflammatory response in meninges is characterized by a reduced glucose content and increased lactate in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The inflammation in the brain blood barrier (BBB) and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (blood-CSF) compromise brain function, ion exchange and mineral homeostasis systemically (Bettinelli et al., 2012). In this regard, we do not know what the condition is for naturally affected pigs. Insight about this could help identify susceptibility factors and define strategies to support health and recovery.

The present objective was to study various outbreaks suspected of S. suis, in our swine research center including the sub-objectives:

- to diagnose the outbreaks

- to evaluate the relative disease impacts,

- to provide new insights on the disease pathophysiology.

Our research farm includes ~160 productive sows organized in batches every 4-5 weeks, producing around 560 pigs per batch with approximately 24 days of age at weaning. Feed research and management studies are running constantly and simultaneously in various sections including gestating sows, lactating sows, suckling pigs and nursery pigs (housed in conventional pens with n = 3-6 pigs/pen or electronic feeding systems with n = 10-12 pigs/pen; fully PVC slats).

When clinical signs compatible with streptococcal disease were observed, blood samples and tonsillar swabs were collected from 2 pigs per pen - one a diseased pig and another one a randomly selected pig. Afterward, sick pigs were medicated with ampicillin and dexamethasone for 3 days. Cases including central nervous system dysfunction were associated with meningitis and defined as severely sick (included loss of balance, ataxia, paralysis, opisthotonos, generalized tremor, and paddling). Other cases with signs other than neurological signs included depression, reddening of skin, and lameness, likely associated with septicemia and arthritis. The randomly selected pen-mate pigs were considered control. Blood samples were taken within 5 minutes of clinical sign detection. Blood and sera were analyzed for gases and minerals. Tonsillar swabs were analyzed by qPCR for S. suis serotypes 2 (and/or 1/2), 7, and 9. The body weight was measured at the time of sampling and repeated in 7 days and retrospective data was searched in our farm records.

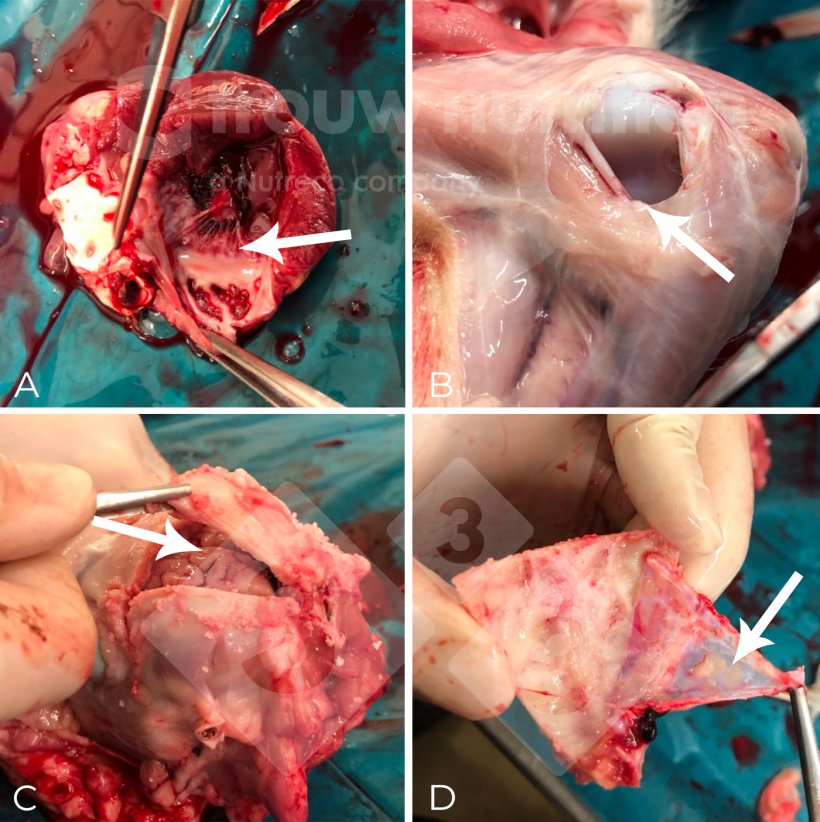

The study included three main outbreaks in winter (3.8% incidence), spring (5.3% incidence) and autumn (9% incidence) batches. Each outbreak was diagnosed and confirmed with S. suis serotype 2 (or 1/2) by presence in tissues by culture or DNA presence by qPCR in tissues (heart valves, joints, meninges) from euthanized and sudden death pigs. However, pigs that were treated and survived were not diagnosed. Besides, not all pigs identified with clinical signs were sampled during this study and cases detected during the weekend or without the human resources for adequate sampling were excluded and immediately medicated.

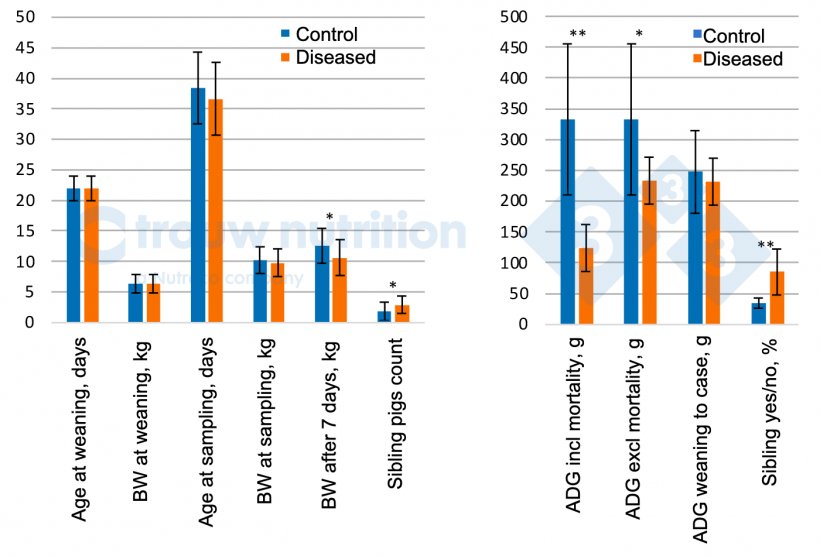

A total of 56 pigs were sampled which included 28 pigs suspected of S. suis disease with clinical signs and included 20 defined as severely sick (neurological signs). Data is reported only for the neurologically affected vs control (Figure 2 A and B) pigs.

Control pen-mates and sick pigs had similar body weight and age at detection of clinical signs and did not differ retrospectively for weaning body weight or average daily gain between weaning and sampling (P > 0.05) which suggests there is no clear pre-condition as extreme poor or good performing pig. Over the 7 days after disease detection, pigs reduced performance as expected (P <0.05).

Retrospectively, a significant sibling/sow effect was observed with a higher proportion of siblings within the neurologically affected pigs than the control (P < 0.02), which is well known and indicates the effect of sow has a vertical transfer of carrier status but maybe a susceptibility factor as well. Sow performance showed no differences between sick or neurologically affected and control pigs which reduces the predictability of potential risk factors from sow performance (data not shown). The prevalence of S. suis serotype 2 significantly (P<0.04) increased in severely sick pigs (81%) vs control (44%) which is in alignment with our diagnostic findings.

A general pathophysiological profile was observed in blood parameters from diseased pigs with neurological signs (Table 1) having increased pH, saturation of O2 and the incidence of alkalosis but reduced glucose, pCO2, iCa, Ca, P, Mg, K, and Na in blood/serum compared to control (P<0.05). Observed respiratory alkalosis was likely related to cerebrospinal fluid acidification (lactate accumulation) from pleocytosis (increased white blood cell count in cerebrospinal fluid). Meningitis may cause cerebral salt wasting syndrome, disrupting the sympathetic system, diuresis, and renal function, explaining mineral loss in this study.

Table 1. Main differences in blood biochemical analysis and mineral analysis in blood or sera for diseased pigs with neurological signs (n = 20) and controls (n = 28).

| Control | Diseased | Root MSE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (blood) | 7.30 | 7.41 | 0.095 | <.001 |

| PCO2 (blood), mmHg | 52.5 | 41 | 9.858 | <.001 |

| PO2 (blood), mmHg | 35.5 | 39.4 | 11.69 | 0.258 |

| sO21 (blood), mmol/L | 57.1 | 67.6 | 17.16 | 0.045 |

| Base Excess (blood), mmol/L | -1.39 | 1.4 | 4.875 | 0.062 |

| Alkalosis incidence, % | 10.7 | 42.2 | 13.2 | 0.019 |

| Na (blood), mmol/L | 139 | 137 | 3.265 | 0.008 |

| K (blood), mmol/L | 5.21 | 4.49 | 0.791 | 0.004 |

| iCa (blood), mmol/L | 1.38 | 1.27 | 0.066 | <.0001 |

| Ca (serum), mmol/L | 2.59 | 2.33 | 0.151 | <.0001 |

| Glucose (blood), mg/L | 117.5 | 82.3 | 21.51 | <.0001 |

Low Na is associated with higher risk of increased disease severity and mortality in children with meningitis (Chao et al., 2008) and low Ca (total and ionized) is common in children with severe meningococcal disease. Mg interacts with parathormone secretion in response to hypocalcemia and might contribute to the poor mineral homeostasis in the present study.

One can speculate that mineral and electrolyte intervention as currently corrected in meningitis human patients may also be beneficial for pigs and more research is needed in that line using controlled infection studies rather than the present case practical approach.

In conclusion, meningitis in naturally diseased piglets was associated with average producing pigs without any pre-disease performance trait to highlight other than a sow/litter effect. Diseased pigs showed respiratory alkalosis, loss of minerals and increased S. suis serotype 2 (and/or 1/2) prevalence.

Extracted from the paper: Metabolic insights and background from naturally affected pigs during Streptococcus suis outbreaks. Fabà L, Aragón V, Litjens R, Galofré-Milà N, Segura M, Gottschalk M, Doelman J. Translational Animal Science, Volume 7, Issue 1, 2023, txad126.