We want to turn our attention to the economics of the sow herd especially since it is the ultimate source of end-product profitability, even when the farm simply sells weaned pigs. The quality of the weaned pig as a finished pig eventually determines the price of the weaned pig either by sorting into marketing categories or by reputation/word-of-mouth. Ever since the production sites have been moved apart with the advent of multi-site production, the communication and the analysis across these geographical and business unit barriers has not been very useful in helping us systematically improve profitability across the entire production process vs. “optimizing” one of its parts.

Many farms have a strategy in the sow herd to simply produce as many piglets per sow as humanly possible, with the last couple of piglets in the calculation often achieved with creative weaning, nurse sow substitutions and other record-keeping tricks. In addition, many farms in the United States create cohort groups for wean-to-finish that are one to two weeks apart in age yet record systems frequently only report one entry date for pigs into the wean-to-finish or finishing phase as groups cannot be tracked separately after entry. These practices are the result of a throughput orientation which creates challenges to important profitability analysis.

There are some studies which give us the “bridges” we need to see how factors in the sow herd eventually affect profitability in the final market but they are not nearly as plentiful as those which confine themselves to analysis of a single phase. One such was published in 2007 by Alison Smith and several others at Iowa State University in the Journal of Swine Health and Production, (Vol. 15, No. 4). I like this kind of research as it provides these “gateways” or “bridges” from one performance period to another.

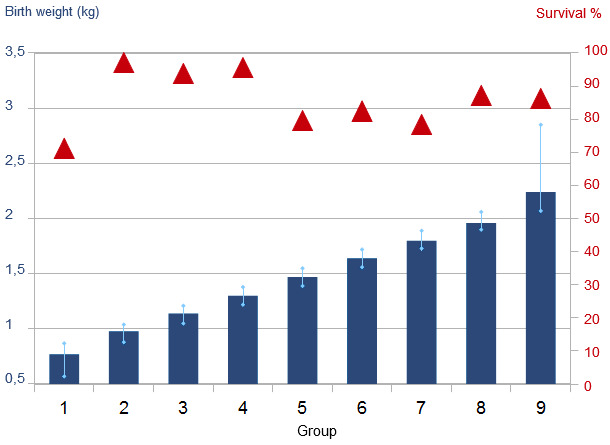

For instance, the researchers divided about 2,900 pigs into nine groups based on their deviations from the group mean birth weight and recorded in addition to the birth weights, wean ages (two groups with different wean ages were created) and weaning weights, survivability to weaning and to 42 days of age and also provided, the individual weights for the groups of pigs surviving to 42 days of age.

The researchers also provide information about parity of the sows for groups of the piglets and measures of variation across the time period from birth to 42 days of age. They really tried to capture a lot of information for one study. Keeping in mind that their results are area, genetics, and even seasonally specific, I am much more interested in patterns which can be observed and the bridges across production phases than the numerical outcomes themselves though they also provide important information.

First, we can really see that the sow herd, like all phases of pig production, requires an understanding of distributions to really comprehend what is going on. For instance, while the researchers report that heavier pigs at birth remained heavier than their contemporaries at weaning and at 42 days, survivability was not equal across weights at birth. In fact, the three weight categories just below the group mean weight had the highest survivability. So you can see that it is not as simple as the larger pigs have better survivability.

In the nine groups of pigs segregated by birth weight (BW), group 2 (mean BW; 0.98 kg / 2.16 lbs.), group 3 (mean BW; 1.14 kg / 2.51 lbs) and group 4 (mean BW; 1.3 kg / 2.86 lbs) had the highest survivability to 42 days at 97.1, 93.8, 95.6 percent respectively. A statistical test suggests the groups have a common mean. This relatively lighter group had lower than the average pre-weaning mortality. The groups with the highest percent reported losses to 42 days were group 1 (mean BW 0.77 kg / 1.69 lbs.), group 5 (mean BW 1.47 kg / 3.24 lbs.) and group 7 (mean BW 1.80 kg / 3.97 lbs.). As expected, the lowest birthweight group had the least likely survivability at 71.2 percent and the other two were 79.6 and 78.4 percent respectively. Again, statistically you could not rule out the same mean for the last two groups.

Table 1: Effect of birth-weight category on survivability to 42 days post weaning.

| Birth-weight category* |

No. of piglets (N = 2893) † | Birth weight (kg) | Survival (%) | |||

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |||

| 1 | 59 | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.08 | 71.2a |

| 2 | 139 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 97.1b |

| 3 | 259 | 1.05 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 0.05 | 93.8b |

| 4 | 405 | 1.22 | 1.38 | 1.30 | 0.05 | 95.6b |

| 5 | 617 | 1.39 | 1.55 | 1.47 | 0.05 | 79.6ac |

| 6 | 566 | 1.56 | 1.72 | 1.64 | 0.05 | 82.5cd |

| 7 | 407 | 1.73 | 1.89 | 1.80 | 0.05 | 78.4ac |

| 8 | 273 | 1.90 | 2.06 | 1.96 | 0.05 | 87.2d |

| 9 | 168 | 2.07 | 2.85 | 2.24 | 0.16 | 86.3d |

* Each piglet was individually identified and weighed within 24 hours of birth. Birth-weight categories incrementally increased or decreased by 0.5 SD (0.16 kg) from the birth weight mean (1.57 kg). Pigs were weaned at an average of 15 days of age (pigs weaned at 14, 15, or 16 days) or at an average of 20 days of age (pigs weaned at 19, 20, or 21 days).

† Includes all pigs born alive.

abcd Means with no common superscript differ (P < .05; ANOVA).

Light blue lines: maximum and minimum birth weight

While your farm and other studies may show different results, in this group nearly 3,000 pigs, three weight categories with average weights just below the group mean had the highest survivability to 42 days. The researchers also found (what most other studies find) that the pigs with the highest birth weights also had the highest weaning and 42 day weights. These kinds of tradeoffs are layered throughout the sow complex and we will use some statistical tools and distribution analysis to take a closer look at profitability implications of some of these tradeoffs. Could be the truisms you hold about the sow herd need a little updating.