Farm introduction

The farm in this case study is a large farm located in the pig-dense areas of south-east Asia. The farm system was established 20 years ago, in older buildings that have been adapted and altered many times since. The owners then financed and organised additions of several large finisher grow-out sites, but these are located within the same farm area covering 20 hectares. Over the past 20 years, the breeder farms had been stocked with a total of 1,000 incoming gilts, consisting of shipments of 100 to 200 pigs from each of various American and European breeding company origins. The breeding herd has been built up from these imports, via multiplication programmes.

The farm system purchased compound feed from a large feed mill operation. Finisher pigs are sold locally to live markets, dealers and small slaughterhouses.

Before the onset of the case problems, breeding sows and gilts received commercial vaccinations against E. coli, parvovirus, erysipelas and leptospirosis. Piglets are vaccinated at various points between 2 and 8 weeks-old against pseudorabies (Aujesky’s disease), Mycoplasma, Japanese encephalitis and FMD (foot and mouth disease) with commercial vaccines.

Breeder-weaner and finisher systems

The farm is located in an area with long periods of very hot and very humid sub-tropical weather. Cooling systems for the pigs consist of water sprinklers, but air movement is restricted in some older buildings, due to lack of adequate fans. The farm area also has known environmental problems with melioidosis (due to Burkholderia pseudomallei) so farm construction design limits pig access to outside areas and rodents and birds (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Typical finisher buildings in the case study farm for south-east Asia farms, with rodent and bird protection.

Pigs are weaned from all gilts and sows at 21 days old, and then raised in adjacent nursery buildings. At around 10 weeks-old, pigs are moved to separate grow-out finisher buildings, usually located 2 km away.

Emergence of the case

The pig farm management team in charge of the post-weaned piglet nursery areas on these breeder to weaner and finisher sites has found serious and consistent problems with on-going cases of PRRS (both American and European strains) and swine influenza (see Figure 2). Like many farms in south-east Asia, the nursery mortality rate generally occurred at 8 to 20 percent, where these diseases were present. The levels of mortality in the finisher sheds were generally of lower levels (1 to 3 percent).

Figure 2. On-going cases of PRRS and swine influenza in 6 week-old weaner pigs.

|

Figure 3. Numerous dead and dying pigs on  |

The farm has a large work-force of local men and women. There is also a small team of technical and veterinary experts, with some outside consultants. On walking and driving around the farm, an inspection is made of their heating, sanitation and ventilation, and of pen and office charts to establish the mortality levels of each section of pigs.

The case situation emerged quickly, with large numbers of dead and dying pigs discovered by workers in the finisher sheds over a 7-day period. The expert team was directed to the affected pens, where the dead pigs were noted. The team confirms clinically that some yellow diarrhoea is evident on the floors of the pens and some coughing was noted, but not in a consistent manner. Many of the remaining pigs were generally dull and depressed, with aimless, ataxic walking and cessation of normal feeding activity. Many pigs had a moderate to copious conjunctivitis, with congestion and thick watery discharge from the eyes. In some pigs, the discharge caused dark streaks around the eyes, with the eyelids gummed and matted together. These pigs often had a fever of 41ºC. The dead and dying pigs usually had a dark congestion and blackened colour to their ears and snouts, indicating cyanosis and hyperaemia in those areas. The feet were normal.

The pen and farm charts indicated a rapid jump to 40 % mortality in several finisher sheds over one to 2 weeks. What this looks like in reality is shown in Figure 3.

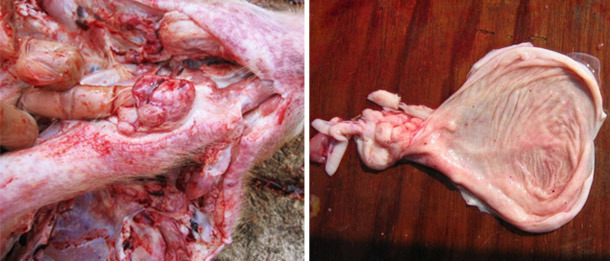

The team performed autopsy on several affected pigs. Care was taken to autopsy both new acute cases and also more sub-acute pigs that had been sick for one week. Many lesions were noted in both groups of pigs. Key features of lesions found in more than one pig, were moderate haemorrhages in the pharyngeal lymph nodes, epiglottis and bladder, see Figures 4 and 5. The spleen usually had raised haematoma lesions. The lungs had some oedema but were otherwise normal.

Figures 4 and 5. Autopsy of affected finisher pig, note haemorrhages in the pharyngeal lymph nodes and bladder.

The team also collected blood from sick pigs into EDTA purple top tubes and submitted them for routine haematology. The normal white blood cell count in pigs is 18.0 x 109 per litre (range 10.0 – 23.0). Affected pigs in the outbreak only had white blood cell counts with an average of 8.5 x 109 per litre.

In pigs that had been sick for 1 week, then autopsied, splitting of the ribs showed distinctive thickening and necrotic calcification of the epiphyseal lines, in 50 to 75 % of cases, see Figure 6.

Figure 6. Rib lesions in sub-acute cases

Differential diagnosis for outbreaks of high mortality in pigs in Asia

Outbreaks of high mortality in groups of pigs can be caused by several important infectious agents. The case study did not appear to be consistent with a nutritional or physical problem such as an electrical fault. The lung findings did not support a diagnosis of APP due to Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Other possible causes of high mortality could include highly pathogenic PRRS and circovirus, with secondary infections, or other agents such as African swine fever or Salmonella cholerae-suis or classical swine fever due to pestivirus.

Analysis of results

The clinical signs, autopsy and haematology results suggest that a pathogenic strain of classical swine fever (CSF) had colonised the finisher sheds in the previous weeks to the mortality outbreaks. While CSF is often described as the “great imitator” with many non-specific signs, the leukopenia and rib lesions are highly distinctive. The signs of cyanosis and haemorrhages and lesions in the lymph nodes and spleen are suggestive, but are not specific. The haemorrhages in the bladder and kidney are strongly suggestive of CSF. The analysis was confirmed with CSF ELISA serology results, comparing serum taken prior to the outbreaks to those from affected pigs.

Further investigation and measures taken

Discussions found that a farm worker had kept small group of native pigs in his home setting and had inadvertently trafficked the CSF virus from his home pigs onto the farm site, via clothes and boots.

The farm workers placed in-feed and in-water antibiotics into the feed and water supply of grower pigs, to try to limit losses in mortality and lost production.

A course of different CSF vaccines from international suppliers, including the live attenuated C strain and the subunit E2 vaccines, was implemented. Better protection efficacy and reduction in case numbers was considered to be achieved with continued usage of the live attenuated strain vaccine.

Full protection for CSF in endemic and high-risk pig farming areas in Asia, even with these vaccination programs, is sometimes difficult, due to early exposure and interference from maternal antibodies. It is therefore often necessary to develop multiple vaccine points around the time of weaning and early grower period.