Description of the farm

The problem appeared in a group of farms with a total of almost 15,000 sows. The company has several farms for the production of piglets and nurseries distributed in the south of Europe, with an average of 1,500-2,000 sows per farm. The fattening stage was integrated, with farms with 800-3,000 pigs each in several locations. The health status was normal: positive to the main pig infections (PRRS, PCV2, App, streptococcal infections). The sows were vaccinated against E. coli, erysipelas, parvovirus and PRRS. In the nursery, vaccines against PCV2 were administered. No antibiotic treatments were given routinely. The feed for the sows and the fattening pigs was produced in two different feed-mills.

Anamnesis and symptomatology

In 2012 we were informed of fertility problems, and the anamnesis performed by the veterinarian described an unacceptable variability in the reproductive performance, even for farms affected by PRRS, with several clinical signs not attributable to a specific management, nutrition of infectious pathology.

Also, there were necrosis on the ears and tails in nursery and fattening pigs, and there were repeated cases of diarrhoea at unusually high weights and ages, rectal prolapses, production losses and an excessive medication expense.

Photo 1: Piglet with necroses on the tip of the ears and on the skin on the flank (which is a typical location in cases of staphylococcal infections) in process of healing.

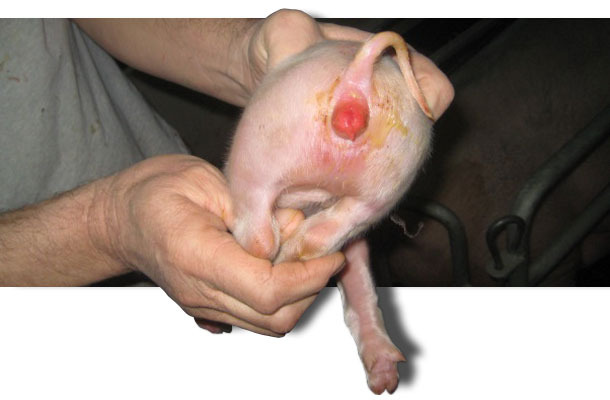

Photo 2: Piglet with advanced necroses on the tip of the ears complicated by a secondary infection.

Some sow farms very far apart were studied in order to verify these symptoms. The general conditions on the farms seemed correct with respect to organisation and hygiene. The symptoms detected during the visits were variable and were distributed differently:

-fluctuating farrowings rate (Fig. 1 shows the example on a farm); some peaks of abortions during some months, sometimes during prolonged periods; loss of appetite in the farrowing quarters, with irregular drops in consumption that could cause dysgalactia during the first weeks after farrowing; piglets with reddened nipples and vulva at birth; necrosis on the tips of the ears at weaning; some skin ulcers with variable locations; recurrent diarrhoeas and conjunctivitis. It was also seen that the ADG was irregular.

Figure 1: Farrowing rate (data of a 9-month period, before the visit, on a farm).

| Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May |

| 92.7 | 85.3 | 87.6 | 87.4 | 89.5 | 90 | 96.5 | 86.3 | 89.1 |

The performance in the reproductive stage was apparently good: farrowing rate: 89.3 %; stillbirths: 8.28 %; 28.1 weaned piglets/year (9 month data).

Diagnostic suspicion

The observed symptoms repeated cyclically, the cause was not easy to identify, we did not have the impression of facing an infection that could justify the clinical picture (performance reduction of the sows, diarrhoea in the farrowing rooms and in the growing-fattening stage related to prolapses, and drop in ADG), and that in some cases seemed related to batches of raw materials or feeds, making us suspect of the presence of toxic substances in the raw materials used.

It was then when the hypothesis of a mycotoxin poisoning appeared. Mycotoxins can be immunosuppressors, causing the variable symptomatology. It is well known that some mycotoxins, such as trichothecenes, can harm the intestinal wall, reducing the intercellular junctions of the epithelium (in synergy with the enterotoxigenic E. coli toxins), inhibiting the SGLT1 pump for the absorption of glucose and sodium and reducing the mucus production (Grenier, 2013). Another mycotoxin, zearalenone, can affect the anal sphincter, with the resulting prolapse.

Photo 3: Group of piglets with necroses on the tip of their ears.

Differential diagnosis

The described symptomatology did not lead us to any specific syndrome. The conjunctivitis could derive from the chronic poisoning with trichothecenes, although it is also present in some cases of PRRS or even in facilities with a bad air circulation; the fertility problems and the skin reddening could be due to a zearalenone poisoning; dysgalactia could also be linked to a poisoning with aflatoxins, trichothecenes or even endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) or mildly pathologic diseases; rectal prolapses can be due to zearalenone, but also to constipation, overcrowding, abrupt diet changes, a post-febrile state or a water shortage; the drop in feed consumption can be due to causes similar to the aforementioned ones.

A blood sampling was carried out in order to verify the presence of the PRRS virus in the animals with symptomatology, but the result was negative. The management practices were considered correct.

The bacteriological analysis of the pigs with diarrhoea detected an E.coli that was sensitive to the most common antibiotics (gentamicin, chlortetracycline, trimethoprim + sulfonamides, doxycycline, colistin, aminosidine, apramycin, enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin, etc.). After this, an assessment of gastrointestinal tracts and livers was carried out in the abattoir, and the result was negative: with no evidences of parasitosis, enteritis nor any kind of acute nor chronic lesion that could represent a specific enteric problem.

The investigation of mycotoxins in the feed did not clarify anything, but it is well known that the fact of not finding mycotoxins in a feed sample does not guarantee its absence. The symptoms pointed towards an immune compromise state, appetite disturbances and clear hyperestrogenism symptoms that, due to exclusion, lead towards a probable mycotoxin poisoning. After that, a therapeutic diagnosis was carried out.

Photo 4: Typical vulvar reddening caused by zearalenone during lactation and very evident diarrhoea caused by coliforms.

Therapeutic diagnosis

So, it was decided to treat during one year a 1,000-sow farm with a product against mycotoxins. It was a product that based its efficacy on adsorption, so it was effective against: aflatoxins, ergotamine, ochratoxin, fumonisin; and an enzyme base for those mycotoxins with no ability (or a low ability) for being adsorbed, such as zearalenone and the trichothecenes (desoxynivalenol, T-2, HT-2, diacetoxyscirpenol, etc.). The product used had been tested, with positive results, as an endotoxin adsorber.

Not being able to create a test group and a control group, it was agreed to compare the production performance of that year (with the treatment) with the data from the previous year.

Results

By the end of the year, the results were compared with those of the previous year: the most evident result was, an average significant increase in feed consumption during lactation, of around 1.4 kg/sow/day. The increase in feed consumption in the farrowing quarters was due to a detoxification: the mycotoxins caused a drop in feed consumption, and their main target organ is the liver.

In the specific case of trichothecenes, a feed rejection neurologic reflex with a direct inhibition of the hypothalamic appetite centre, and a stimulation of the vomit stimulation centre have been shown (Bonnet et al., 2012).

According to the report of the farm veterinarian, less diarrhoeas were detected, together with a lower consumption of medicated feeds, more regular lactations, and almost without dysgalactia cases. In the nursery, the necroses on the ears, tail and skin had dropped considerably. In the sows that were not treated during that year, the symptoms described appeared from time to time.

In the fattening stage, not treated initially, the treatment made diarrhoeas and prolapses disappear.

The following table shows the improvement of the general performance of the treated sow farm:

| WTSI (days) | Stillbirths (%) | Born alive (no./sow) | Weaned/sow/year (no.) |

| - 1.4 | - 1.7% | + 0.4 | + 1.2 |

The final result has convinced the owners to adopt a permanent anti-mycotoxins strategy aimed at a higher control of the raw materials at their entrance, the use of the best raw materials for the younger animals and the breeders, and the use of a valid product against the most frequent mycotoxins in the region.

It is clear that the synergy between the veterinarian, the nutritionist and the manager of the farm is necessary in order to implement strategies that cannot be carried out individually. There is the need of a great amount of information from the different stages, and the need of an honest contribution of these people to take the correct decision and justify some management expenses (see feeding) that the producer would not accept otherwise in a competitive market.