1. Definition

Mycotoxins are organic chemical compounds with a low molecular weight and a great stability with respect to pH conditions and temperature. Currently, some 500 different mycotoxins are known.

They are produced by toxigenic strains of moulds that contaminate the raw materials during their cultivation and/or storage. They are secondary metabolites that are only produced under certain environmental conditions that stress the mould (CO2, O2, concentration of minerals, temperature, water activity, pH, etc). The genera Fusarium, Aspergillus and Penicillium are the main culprits, although Claviceps, Alternaria, Cladosporum and Dreschlera can also appear as producers of mycotoxins. These moulds genera are famous for their ubiquity.

Their stability and the fact of being secondary metabolites are factors that are responsible that high levels of mycotoxins may be found in raw materials that are not very contaminated by moulds, because they remain even though the moulds disappear; as well as the fact that high levels of mycotoxins may not be found in raw materials with high levels of mould contamination, because the conditions for the production of mycotoxins may have not been met, or because these moulds may not belong to toxigenic strains.

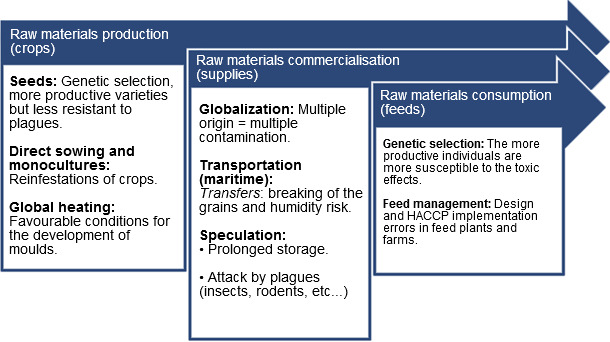

Currently, they entail the main danger for the swine production and feeding sector in terms of human food safety because of the probability of its appearance and the seriousness of the direct effects (financial losses related to the drop in production) and the indirect effects (presence of mycotoxins in animal tissues). The hazard due to mycotoxins has been identified as an emerging potential hazard by the EFSA, and some of the predisposing factors for this increase in the incidence are the ones shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Main predisposing factors for the contamination with mycotoxins.

2. Classification

The classification mostly used has been the one based on the mould that produces the mycotoxin and/or the stage of the production of the mycotoxin, whereas in the field or during storage, but as investigations in this field progress, we discover that this classification is too flexible, because a genus can produce several kinds of mycotoxins, and it can do it in the field as well as during storage. Currently, the classification used is based on the chemical structure and polarity, and there are seven groups (Fig. 2):

Figure 2. Groups of mycotoxins according to their chemical structure

| GROUP | Mycotoxins | Main moulds that produce it | Chemical structure |

| Aflatoxins | Aflatoxin B1 Aflatoxin B2 Aflatoxin G1 Aflatoxin G2 |

Aspergillus sp | Dihydro or tetrafurans |

| Ochratoxins | Ochratoxin A Ochratoxin B |

Aspergillus sp Penicillium sp |

Isocoumarin derivatives |

| Trichotecenes Type A |

DAS, T2, TH-2, etc… | Fusarium sp | Tetracyclic skeleton |

| Type B | DON, nivalenol, etc… | ||

| Fumonisins | Fumonisin A Fumonisin B |

Fusarium sp | Hydrocarbon chain |

| Zearalenone | Zearalenone | Fusarium sp | Macrocyclic lactones |

| Alcaloids | Ergot, etc… | Claviceps sp | Alcalenes |

| Others | Patulin, Roquefortine, etc.. | Penicillium sp | Various |

3. Toxic effects

The toxic effects are determined by the ingested dose, the length of exposure, the interaction with other toxic substances and the genetic susceptibility of the individual. These effects on the animals' health are called 'mycotoxicosis', and they can be clinical or subclinical, and acute or chronic. The affected organs are mainly those that are responsible for the metabolism (liver, kidneys and lungs), but they also affect the central nervous system, the immune system and the reproductive system.

Although in pig production acute clinical effects on the digestive and immune systems are especially important (weight loss, predisposition to infectious diseases, etc…), as well as those related to reproduction (abortions and infertility, weak piglets, etc…), we must not forget the importance of the subclinical chronic effects (increase of the feed conversion rates, predisposition to infectious diseases, reduced longevity of the sows and boars, etc…), which entail a continuous loss of production efficiency, genetic potential and profitability of the farm.

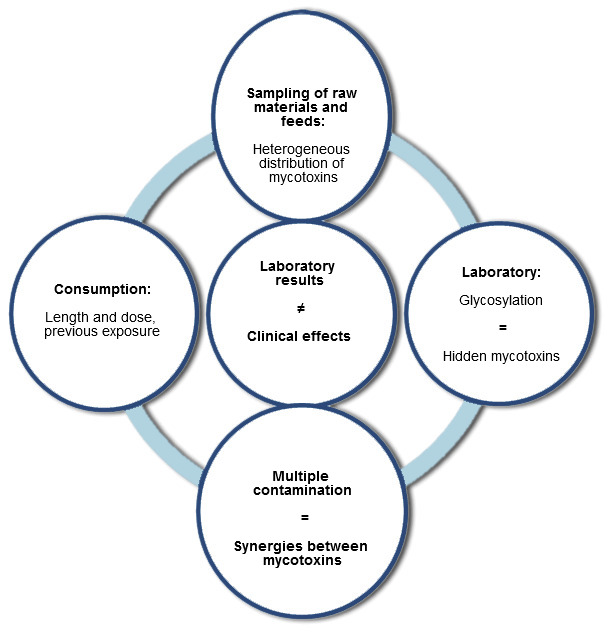

Sometimes the laboratory results obtained after the appearance of a problem in which we suspect the presence of mycotoxins do not match with the observed clinical effects, and this is mainly due to the factors summarized in Fig. 3

Fig. 3. Factors related to the variability of the clinical effects and the laboratory results.

The European Commission and the animal feeding sector work together gathering information related to the presence of mycotoxins in raw materials for establishing maximum limits or recommendations. Whilst they are officially established, the practical reference levels used for the main mycotoxins that affect swine appear in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Reference levels of the main mycotoxins that affect swine

| Mycotoxin | Maximum level (ppb) | Alert level (ppb) |

| DON | 900 | 250 |

| T2 | 1,000 | 50 |

| DAS | 2,000 | 50 |

| ZEA Piglets and gilts Fattening pigs, sows and boars |

100 250 |

100 250 |

| OCRA A | 50 | 25 |

| FUM (B1+B2) | 5,000 | 2,500 |

| Aflatoxin | 20 | 20 |

| Ergot | 6,000 | 500 |

The EU regulations that are to be applied regarding mycotoxins are (Fig. 5):

Fig. 5. Reference regulations regarding mycotoxins

| Maximum levels | Sampling and tests |

| Directive of the European Parliament and the Congress 2002/32/CE of May 7th 2002 about undesirable substances in animal feeding (and modifications). | Regulation of the European Parliament 401/2006 of February 23rd 2006 that establishes the sampling and testing methods for the official control of the contents of mycotoxins in food products. |

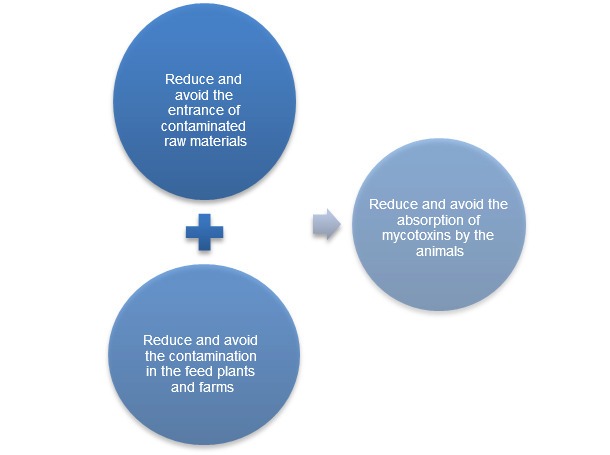

Given the complexity of the problems due to mycotoxins in pig production, a preventive strategy must be assumed in order to try to achieve an ALARA (as low as is reasonably achievable) contamination level using the principles reflected in Fig. 6, because the current decontamination systems do not have a good cost-effectiveness, and in Europe, the 'dilution' of raw materials and contaminated feeds is forbidden.

Figure 6. Prevention strategy against mycotoxicoses in pig production.