The so-called transition period (TP), which includes the last ten days of gestation and the first ten days of lactation, is receiving increasingly more attention. Nutrient requirements during the TP change rapidly, both for energy and for protein and amino acids.

Generally speaking, we can say that gestation diets have low protein and energy density, while lactation diets have high protein and energy contents, as well as very different levels/quality of fiber and digestible calcium/phosphorus, which represents both a quantitative and qualitative jump that must be taken into consideration. In practice on the farm, often limited by infrastructural and management factors, the transition from one feed to another is done according to what each person sees fit, meaning what is easiest, and not necessarily what is optimal from a nutritional point of view.

When faced with any problem in lactating sows, we must go over everything we have done on the sow farm during the previous six months. There cannot be a proper lactation phase if we have not correctly managed and supplied proper nutrition to the sows during the previous lactation and from the moment they were weaned from the previous cycle until the time they entered the farrowing room.

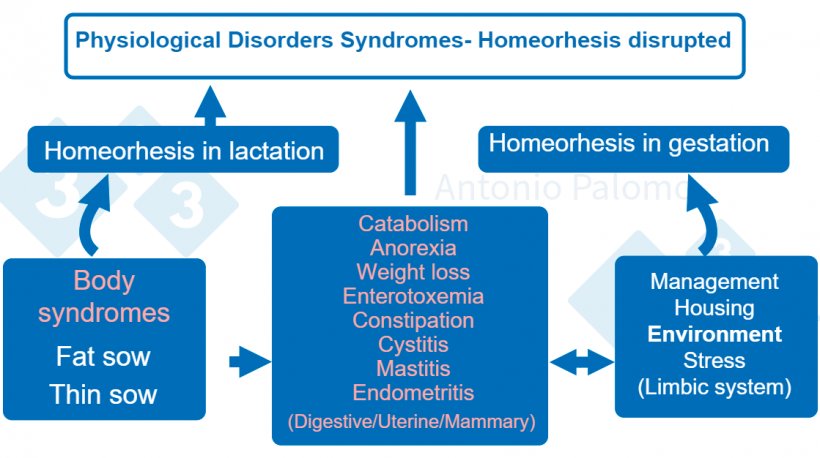

At this point, maintaining homeostasis and body condition of the sows will be critical to understanding many of the disorders that can arise if there are deviations from these two major aspects of the basis of metabolism. These are represented in the following graph:

Figure 1. Metabolic disorders in breeding sows. Post-farrowing pathophysiology, 2015. (Palomo, 2015).

Aspects to keep in mind when considering nutritional needs in the TP:

- Fetal growth

- Mammary development

- Maintainance needs

- Sow weight gain needs

- Mobilization of body reserves

- Colostrum production

- Milk production

- The sows' parity number: first and second parity vs. multiparous sows.

- Weight of the sows at said productive stage based on genetics

- Productivity of each sow

Critical points affected in practice by nutrition in the transition period

1) Fetal growth and litter weight at birth: Almost half of the weight at birth takes place in the last 3-4 weeks of gestation. It is estimated that fetal growth during the first half of the TP accounts for 25-30% of the weight at birth. This involves an increased need for protein and amino acids in the sow. If nutrient intake during these days is not sufficient for body maintenance, fat and protein reserves will be mobilized for fetal and reproductive tissue growth. This does not mean that it will linearly influence piglet birth weight, but it will negatively influence the reproductive physiology of the sow. As we do not know the exact number of fetuses, it is difficult to establish the exact nutritional requirements.

2) Growth of the placenta, uterus, and amniotic fluid: The amniotic fluid and the membranes increase starting at the beginning of gestation until day 80-85, so their variations in the TP do not have a major influence on nutritional needs. In contrast, the exponential growth of the placenta and uterine horns does have an influence based on their amino acid content. At the end of farrowing, the nutrients retained in the expelled placenta, fluids, and membranes are lost by the sow, resulting in a negative balance. Conversely, when regression of the two uterine horns takes place, the nutrients this provides pass into the blood and go into milk production. It is not known precisely how sow nutrition in this transition period affects the regression of uterine tissue.

3) Mammary tissue development: lactogenesis begins at 90 days of gestation, recognizing that mammary growth takes place in the last third of gestation, with greater development in the last ten days prior to farrowing (despite visual perception) and is divided into two phases:

- Phase I: preparation of mammary tissue for the synthesis of milk constituents

- Phase II: colostrum secretion. The greatest growth of mammary tissue takes place in the ten days prior to farrowing, continuing for ten days after farrowing, but at a slower rate. Nutrition in this period plays a key role in mammary development.

4) Production of endogenous heat: milk production leads to an increase in heat production. Maintenance energy needs are higher during farrowing than in gestation, being constant based on metabolic weight (460 vs. 405 kJ/kg - NRC 2012) which tells us that in the ten days prior to farrowing the sow's maintenance energy needs remain constant, depending on the sow's weight. On the first day after farrowing, due to the quantity/composition of colostrum, the additional endogenous heat loss is low, but starting from day 2 post-farrowing, heat loss increases considerably in relation to the amount of milk produced. Between day 2 and day 10 of lactation, the increase in heat production is equivalent to the energy content of half a kilogram of feed.

5) Adaptive physiological processes: the gestation phase is considered a period of anabolism while during lactation we are in a period of catabolism. As a general rule, of the energy ingested by a sow in gestation, 70% is to cover her maintenance needs and only 30% is used in production (fetuses, placenta, amniotic fluid, membranes, uterus), while in lactation this 70% is used for milk production, which is much more metabolically demanding than fetal production. This involves a change in liver metabolism with a three-fold increase in arterial plasma flow and an estimated +40% increase in oxygen consumption by the liver during lactation. An essential function of the liver during this period is to maintain glucose homeostasis, with glucose being more efficiently utilized from body reserves than from the feed itself. This should cause us to reflect on the importance of glycogen reserves in this transition period, accumulating as much as possible in the last ten days of gestation and avoiding a great depletion of these reserves in the first ten days of lactation by means of high feed intake on a continuous basis. When there are more than four hours between feedings in hyperprolific sows, plasma glucose levels drop dramatically. Studies have been done on the relationship between plasma urea levels in sows at farrowing and colostrum production showing a positive correlation (Loisel, 2014) demonstrating that liver metabolism affects the productivity of sows during the transition period, given that urea is produced in the liver (protein oxidation).