The current trend in the swine industry is to speak about “holistic” approaches. For instance, when targeting the withdrawal of therapeutic ZnO or antimicrobial reduction, scientific evidence indicates that several factors are intimately interconnected and that effective strategies normally imply changes related to management, nutrition, health, and welfare.

The industry and science are aware of such holistic needs (for instance, the gut-brain axis or the microbiota-immune system crosstalk are nowadays hot topics in many sector meetings), but we still lack the practical comprehension and changes in different aspects to achieve such final objective. For instance, is the nutritionist aware of the farm’s sanitary status and vaccination protocol? Should they be? Let’s discuss this.

First, although we’re still far from being able to do a complete science-based nutritional immune-management, the interrelation of these two aspects has been largely researched and acknowledged. Table 1 (adapted from Klasing, 2007) broadly summarizes the main mechanisms by which diet affects immunity.

Table 1. Main mechanisms by which diet affects immunity. Adapted from Klasing, 2007.

| Mechanism | Nutritive and non-nutritive feed components |

|---|---|

| Nourish the cells of the immune system | All |

| Nourish pathogens | Biotin, iron |

| Modify the responses of leukocytes | Energy, PUFA, vitamins A,D,E |

| Protect against immunopathology | PUFA, vitamin E |

| Influence microbiome | Antibiotics, fibre, prebiotics, probiotics, acids, phytobiotics |

| Stimulate immune system | Lectins, protein antigens |

Secondly, when speaking about the modulation of immunity, we all have vaccines in our minds. A normal criterion when designing a vaccine is to be able to be effective “independently”, without needing external inputs, either with one or two shots. Still, it is well-established that nutritional deficiency or inadequacy can impair immune functions (Wu et al. 2019). This can be a problem in certain least-cost diets, if they are optimal for growth based on standard requirements, they’ll normally focus on delivering energy and can be marginal in some nutrients that would be needed for optimal immunity.

Still, even if we consider an ideal situation, with no deficiency in terms of nutrients for immunity, could we still influence and get more from vaccination by modulating the diet?

Recent research evidence (Borey et al. 2021), described an association between pre-vaccination fecal microbiota and the response to vaccination against Influenza A virus in pigs. A higher vaccine response was found in piglets with a richer microbiota, and a stronger immune response was linked to the bacterial genus Prevotella and family Muribaculaceae.

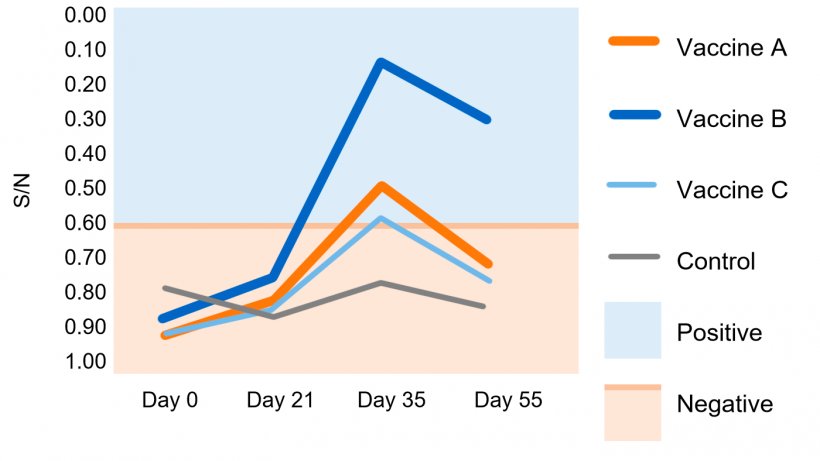

This could have actual implications in present commercial Swine Influenza Virus (SIV) vaccines, as Martinez et al. (2015) assessed the immune response of different commercial products and reported that two vaccines, Vaccine A and Vaccine C, showed a limited humoral response, despite being a key factor for developing the clinical protection in front of the infection of swine influenza virus (Matthew et al., 2015). Hence, the farms using these products may benefit from a (nutritional) strategy to improve vaccine response.

Moreover, swine influenza virus is just an example, but more and more data are being reported correlating vaccination response against many common pathogens in swine to certain gut microbiota. It was firstly described in pigs by Munyaka et al (2020), who detected higher IgG production after Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccination in animals with Prevotella (same as before), Anaerovibrio, and Sutterella. Furthermore, Zhang et al (2021), recently reported that for PRRS vaccination the antibody titer after piglet vaccination was positively correlated with the abundance of Lactobacillus in immunized pigs. The practical interest of all these results, is that diet is one of the main factors that can influence microbiota (Guang Pu et al., 2020), so could a differential diet modulate these responses?

All in all, historically the interest and research in the nutrition field has mainly focused on achieving optimal performance parameters. This approach was great in a context of all-in-one solutions, where antibiotics or ZnO would make unnecessary any other intervention. However, in modern pig production, with a context of antimicrobial and ZnO restriction, there is the need to find alternatives and (as commented at the beginning), many of them are based on embracing a “holistic” approach.

During this past decade there have been great efforts (with more or less success) on investigating and developing nutritional strategies aiming to build immunity/health in specific critical phases such as weaning, but this is not translated yet to this “holistic” approach. For instance, should we adjust the use of specific additives or nutrient levels to vaccination protocols? Should we change nutritional requirements based on sanitary status and immune challenge? Should we monitor specific microbiota profiles to decide which vaccine or additive to use?

Probably we’re far from being able to answer or apply some of these ideas… but we’re going in this direction. Nutritional immunomodulation can be used for real-time adjustments, to guide the immune system in protective directions. If your nutritionist is not aware of the farm’s vaccination protocol… you may be losing an opportunity.