In 2015 Spain became the country with the largest pig population in Europe. Spain produces more pig meat than it can eat, and because of this, it has become a big exporter. Such dependence from foreign markets should push the Spanish pig industry to think about its health situation regarding zoonotic infections, such as salmonella, which could be, a future barrier to trade.

Since the first data regarding the Salmonella pig infection prevalence in the EU was published in 2008, and Spain was revealed as the country with the highest proportion of infected pigs (1/3 of all slaughtered pigs), the situation has changed very little. While 21,2 cases of human salmonellosis were recorded in the EU for every 100.000 inhabitants in 2015, the number of confirmed cases in Spain were twice as many (43,3 cases). The global economic crisis, that started shortly after this reference study was carried out, and the scarcely encouraging results of the cost-benefit models carried out, hampered any European common initiative to control this infection in swine. And all this in spite of there being an increasing number of reports about pigs and pork products being responsible for Salmonella infections in the population. So it was every country, individually, through public or private initiatives, who decided to implement Salmonella control programs on farm.

Of the 6 main pig exporting countries in the EU, only Spain has not yet started any type of Salmonella farm control program (Figure 1). Even the United Kingdom, a distinctly importing country, started a program in 2002. Catalonia, through an initiative led by the meat industry, recently started a control program based on the ones launched by other countries some time ago . But ... have we given any thought to the analysis of the results achieved in those countries before copying their control programs?

Figure 1. Main pig exporting countries in the EU. Percentage of self-sufficiency and starting year of the Salmonella control program. Source: from data of Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, 2016.

I

In general, all the programs established to control Salmonella on pig farms have been based on the Danish model, that implies a small serological sampling in slaughter pigs (usually from meat juice) throughout the year and the determination of the "seroprevalence level" in the farm and, therefore its “risk level”. In high risk farms, the producer is “encouraged” to adopt actions to reduce its risk level, which means, to reduce their Salmonella exposure.

With more or less differences, this type of programs, which were followed by several countries, have proved to be rather ineffective. In fact, in the last few years the UK and Belgium decided to halt them. After more than 10 years, Germany has still not reached the objectives set up initially. And there are no news about the success of the programs carried out in Holland and Ireland.

There are several possible reasons for this “failure”, but perhaps the most important one has to do with the very poor correlation between the serological status of a farm and the real status of the infection, mainly due to inadequate (not representative) sampling, an insufficient number of samples and serological tests of limited diagnostic accuracy. The perfect cocktail for missing any potential correlation between what we see and what is really happening. Besides, given that this a is very variable infection —not only throughout time, but even between different batches within the same farm— the results obtained refer to a past situation on the farm that will not necessarily repeat itself in the future.

There is no doubt that, if Spain wants to control this problem, a new set of strategies must be applied. One of them could be to focus directly on preventing the infection in humans, instead of assessing the farm status retrospectively. Therefore the objective would be to prevent the animals going to be slaughtered from shedding Salmonella when they reach the abattoir, as they are the main responsible for carcass contamination.

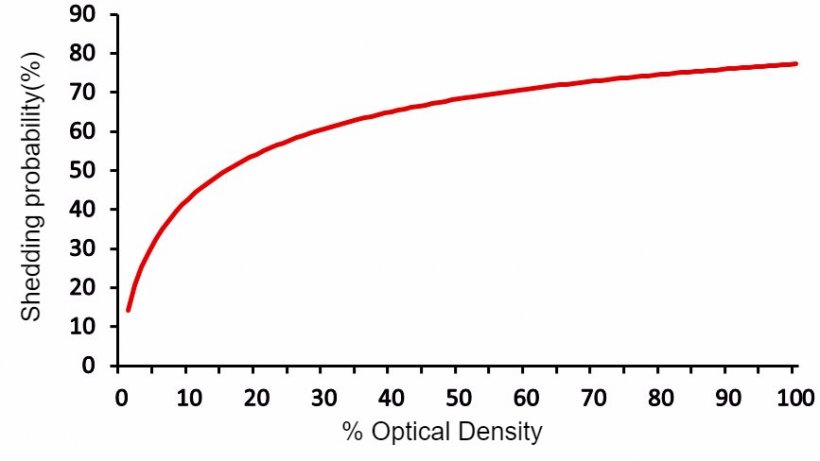

Figure 2. Estimated probability of excreting Salmonella at the slaughterhouse depending on the result of the ELISA blood test from a pig sampled at day 90 of the finishing period (Mainar-Jaime et al., 2017).

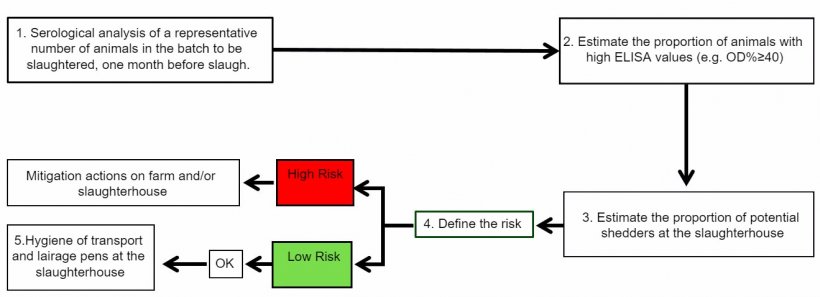

In a recent study, a positive correlation was established between the ELISA test result during the finishing period and the probability of shedding Salmonella at the slaughterhouse (Figure 2), which suggests that this new objective could be achieved if: 1) serum samples of a larger and more representative number of animals in the batch of pigs to be slaughtered are taken sufficiently in advance (approximately one month before slaughter) and 2) mitigating measures are applied at the farm and/or slaughterhouse to reduce shedding (for example, the addition of organic acids, mannan oligosaccharides, etc. to feed or water) and contamination (extreme hygienic measures) whenever a batch of pigs with a high proportion of potential Salmonella shedders is detected. Although the effectiveness of this new strategy will have to be confirmed by a larger study, it would mean, briefly, doing something similar to what can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Potential strategy to control Salmonella in pigs

This strategy would allow us to, not only be pro-active in the reduction of Salmonella excretion at the slaughter house, but also to classify herds based on their serological results, albeit with greater accuracy, as the result would be obtained from a larger number of animals and, more importantly, more representative of the batch to be slaughtered. The implementation of this strategy could be integrated, as much as possible into the current official control programs (for example Aujeszky´s disease) with the aim of reducing costs.