Recent pandemics (COVID-19 in humans, African swine fever in pigs) have shown that the systematic collection of population health data are needed to understand the situation and guide an effective response. Collecting population health data in pigs has been problematic because clinical signs are highly variable and individual animal sampling/testing is expensive. In contrast, oral fluid-based surveillance is easy, accurate, and cost-effective.

Oral fluids are collected from individuals or group of pigs by suspending a length of cotton rope in the pen, allowing the pigs to bite/chew the rope, and then recovering the oral fluid from the wet rope. More than 23 pig pathogens have been shown to produce detectable levels of nucleic acid and/or antibody in oral fluids, including our most significant health challenges (e.g., African swine fever, Classical swine fever virus, Foot-and-mouth disease virus, influenza A virus, PCV-2, PED, and PRRSV). In North America, oral fluids are widely used to monitor swine populations, e.g., the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory performed ~1.4 million tests on swine oral fluid samples between 2010 and 2019.

First things first:

- What is your long-term health objective(s)? How will surveillance help you achieve your herd health goal(s)?

- Understand the oral fluid collection process. Many videos on oral fluid collection are available online.

Oral fluid collection:

- Plan ahead. Have supplies in place (rope, cutters, sample tubes, etc.). Maintain biosecurity, i.e., avoid carrying supplies between barns.

- Collect samples early in the morning. Pigs are more active first thing in the morning. Collect before feeding, if on a feeding schedule.

- Use pig psychology. The first time pigs are exposed to the rope, allow a bit more time for them to learn the process (~45 minutes). If the pigs are afraid of the hanging rope, place a length of rope (one meter with knots on each end) on the floor for ~30 minutes. Once they have begun playing with the rope on the floor, lead pigs to the place selected for collection by slowly dragging the rope (drag it on the floor and the pigs will follow) and then hang a new length of rope for them to chew. Note that applying attractants or flavorings to the rope has shown little benefit.

- Who to sample? Pre-weaning pigs are sampled by collecting family oral fluids (sow and piglets). Individual or pen-based oral fluids can be collected from pigs of ≥ 21 days of age, including group housed sows. Collection of oral fluids from individually housed boars and sows can be done, but requires training (see #3) and is generally not practical in large commercial systems.

- Follow a routine. Hang the rope at the same place at the same time of day to establish a routine. Pigs will quickly learn the process and will know exactly what to do at subsequent samplings. Once a pattern is established, collection time may be shortened to 20 minutes. Do not leave the rope in the pen for an extended period of time (hours) because (a) the sample will be lost over time as the rope dries; (b) pigs are strong and will destroy the rope, if given enough time; (c) pigs become bored with the rope and will simply ignore it.

- Avoid excessive sample contamination. Set the bottom end of the hanging rope at the height of the pigs’ shoulders to avoid contact with the pen floor. Organic material will not directly adversely affect the tests' performance (RT-PCR or ELISA), but cleaner oral fluids are easier to pipette and handle in the laboratory.

- Use one clean plastic bag and tube per sample. To harvest the sample, place the wet portion of the rope in a plastic bag, extract the oral fluid, and then place the sample into a container (pre-labeled). Remove the rope after you collect the sample so that the hanging rope remains a novelty for the pigs (again, pigs get bored, too!).

- Take care of the sample. Chill (4°C) immediately after collection by placing on ice or under refrigeration. Calculations based on data from Prickett et al., (2010) estimated the half-life of PRRSV RNA in oral fluid as ~13 hours at 30°C, ~42 hours at 20°C, and ≥ 14 days at < 10°C. No PRRSV antibody was detected in oral fluids after ~72 hours at 30°C.

Surveillance applications:

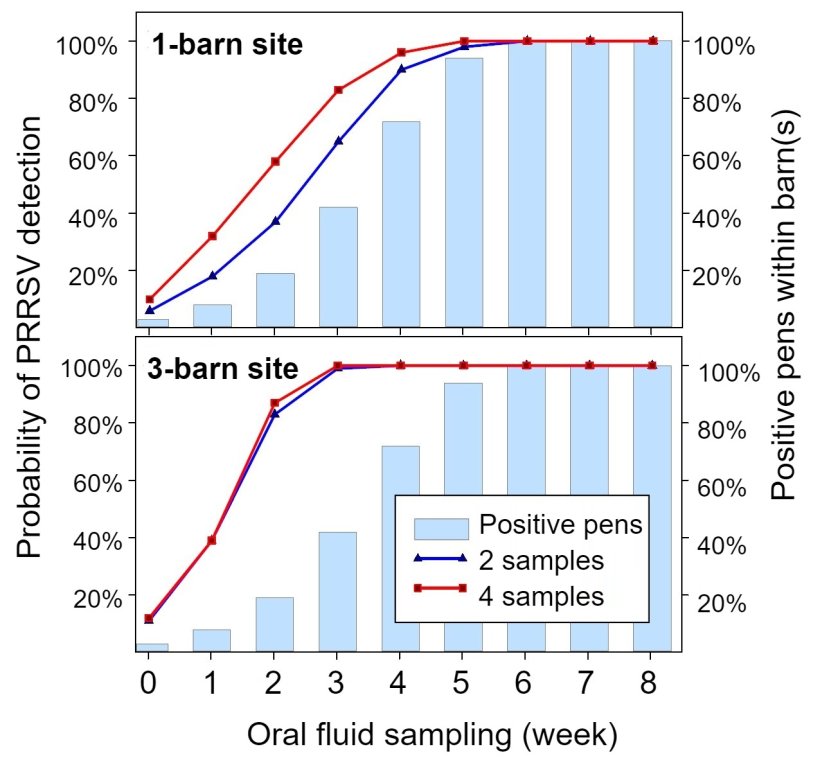

- How many samples to collect and how often? Everybody needs to live within a budget. Even so, even a few samples (2 to 4) collected in each barn (or room) at set intervals (every 2 to 4 weeks) will produce an eloquent narrative of herd health history vis-à-vis herd productivity (Figure 1).

- Have a plan for evaluating surveillance data over time. For example, statistical process control charting.

- Use "fixed spatial sampling" within the barn to maximize detection. An explanation of "fixed spatial sampling" in a barn or site is available online:

- Oral fluid sampling in English

- Oral fluid sampling in Spanish

- Expect the unexpected. Have a plan for verifying or refuting unexpected results, e.g., re-test in duplicate, re-sample, or test with a different assay.

- Remember the natural history of the diseases to set a plan. Nucleic acids tests will detect early presence of the virus while antibody testing will detect the resultant and extended immune response. Both technologies works better together for surveillance, e.g., releasing animals from quarantine.

Other considerations:

- Zebras and horses … things that seem similar may be different. Specimens that seem similar to oral fluids, e.g., buccal or nasal swabs, may not provide the same rate of detection over time. Examples for influenza A virus, foot-and-mouth disease virus, Senecavirus A, and PRRSV are given in Table 1.

- Do not pool oral fluid samples and do not "pass" the rope from pen-to-pen. Rather than improving detection, these processes can create false negatives.

- Avoid freeze-thaw and/or extreme temperature fluctuations. Antibody in oral fluid can tolerate multiple freeze-thaw cycles, but nucleic acids cannot. If multiple testing on one sample are required, the best approach is to split samples into several aliquots and then use one aliquot per test. On the farm, do not store samples in self-defrosting freezers because the defrost cycle may damage nucleic acids. In the laboratory, thawing oral fluid samples at 4°C (not room temperature) was shown to optimize the detection of PRRSV RNA (Weiser et al., 2018).

Table 1. Comparison of nucleic acid detection in oral fluids vs individual pig buccal or nasal swabs.

| Pathogen | Specimen | Rate of detection (%) by day post inoculation (DPI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | ||

| Influenza A virusa | OF | 100 | 100 | 75 | 25 | 38 | 29 | 29 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Swabs | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| FMDVa | OF | 75 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 | nd | nd | 100 | nd |

| Swabs | 4 | 33 | 61 | 100 | 89 | 50 | nd | nd | 25 | nd | |

| SVAa | OF | nd | 67 | nd | 100 | nd | 100 | 100 | 100 | nd | 100 |

| Swabs | nd | 92 | nd | 100 | nd | 75 | 67 | 75 | nd | 8 | |

| PRRSVa | OF | 0 | 20 | 60 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 20 |

| Swabs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

nd = no data.

a Positivity rate (mean) estimated on pen-based oral fluids and individual buccal swabs. Data from Hole et al., (2019); Pepin et al., (2015); Romagosa et al., (2012); Senthilkumaran et al., (2017).