Swine Influenza Viruses (SIV) belong to the genus Influenzavirus type A, Orthomyxoviridae family. These viruses are further classified based on the surface glycoproteins: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), of which 17 and 10 different types have been described respectively. The combination of a type of HA with a type of NA is what defines the subtype. Thus, the major subtypes in pigs are H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2.

Based on various studies conducted in Europe, the seroprevalence of the three subtypes (H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2) is very high in those countries with a large pig production. For example, in Belgium, Denmark and Spain, the seroprevalence of the three subtypes is higher than 30%. In Spain, 94% of farms are positive to at least one subtype. In France and the UK high prevalence of H1N1 or H1N2 can be detected; however, the H3N2 subtype has not been recently isolated. In other countries such as the Czech Republic, Ireland and Poland, the prevalence of SIV seems to be lower.

In the same herd, more than one SIV subtype can be detected directly (PCR + sequencing) or indirectly (by hemagglutination inhibition). In fact, this situation has been demonstrated in farms in the Netherlands, France and Spain, among others. Individually, the proportion of animals with antibodies to more than one subtype can be high in both sows and fattening pigs. This suggests that SIV infection is active and frequent. In spite of this, the virus is not always associated with respiratory disease outbreaks; in fact, there is a high number of positive farms without apparent clinical signs caused by the virus. In short, these findings suggest that SIV is present in a high proportion of pig farms causing an enzootic and apparently subclinical infection.

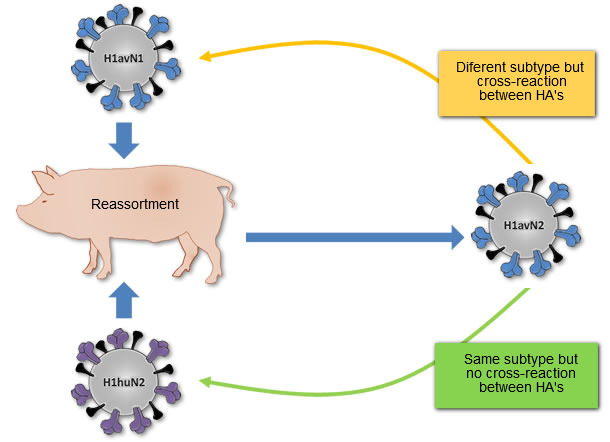

Figure 1. Origin of H1avN2 virus described in Denmark and France. This virus was generated from the reassortment of the H1avN1 virus (HA donor) and the H1huN2 virus (NA donor). So, H1avN2 and H1avN1 belong to different subtypes but their HA’s cross-react. H1avN2 and H1huN2 belong to same subtype, but their HA’s do not cross-react.

The classification subtypes is useful to simplify and to understand the epidemiology and diversity of SIV; however, SIV diversity is much more complex. The genetic diversity of European SIV has been widely summarized by Dr. Simon. Briefly, we can distinguish at least four lineages in Europe depending on the type of HA; 1) viruses related with the avian-like H1N1 type (H1avN1), 2) viruses related with the reassortant human-like H1N2 (H1huN2), 3) viruses related with the H1N1 pandemic (H1N1pdm) and finally, 4) the H3N2 viruses.

It is important to remember that SIV, as other viruses belonging to the genus influenzavirus A, are composed of a genome segmented into 8 pieces of RNA allowing genome evolve through two mechanisms: 1) Drift; mutations occur in specific places of the HA (mainly) or NA. It can generate viral variants that can escape from immunity previously generated against SIV ancestors (main cause of seasonal flu in humans). 2) Reassortment; it occurs when two or more fragments of RNA viruses exchange (for example, the generation of H1huN2 strain in 1994 resulting from the reassortment between a human H1N1 and a swine H3N2).

Although the three different H1 (H1avN1, H1huN2 and H1N1pdm) had a common ancestor at some time point in the past, they do not show cross-reaction at antigenic level or they do it scarcely. Probably it occurs because the three variants of H1 have evolved by drift in three different species before entering the pork in Europe; the H1avN1 in birds, the H1huN2 in humans, and the H1N1pdm in pigs in North America. Moreover, reassortment can generate new strains of influenza viruses that although belonging to a given subtype, they can cross-react antigenically with viruses belonging to other subtypes. A clear example is the H1avN2 strain described in Denmark and France. This strain contains an HA related to H1avN1 strains and consequently does not cross antigenically with the H1huN2 strain, but it does it with the H1avN1 strains (see figure 1).

Genetic and antigenic diversity of influenza virus should be understood as something dynamic and constantly evolving. This notion has been demonstrated in works recently done in Germany, Denmark, Spain and Italy. In these works, new SIV strains have been isolated and characterized, and it has been pointed out that they are product of the reassortment between SIV strains and human seasonal flu viruses. For all these reasons, it is crucial to maintain and even encourage active surveillance of SIV in order to improve our knowledge of the SIV strains present in the European pig and their particular prevalence and impact in swine production.