Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)-induced reproductive problems are characterized by embryonic death, late-term abortions, early farrowing and increase in number of dead and weak fetuses. Recent findings indicate that the endometrium and placenta are involved in the PRRSV passage from mother to fetus and that virus replication in the endometrial/placental tissues can be the actual reason for fetal death. Better understanding of these phenomena may facilitate preventive strategies.

The presence of PRRSV target cells in the endometrium and placenta may be essential for virus passage from mother to fetus. In line with this, the highest number of CD163+ and Sn+ cells (target cells for PRRSV infection) is observed in the endometrium and placenta collected at 90-110 days of gestation than at earlier stages. The abundance of cells that are highly susceptible to the virus in the placenta in late gestation may in part explain why congenital PRRSV infection is mostly restricted to the end of gestation. A previous challenge experiment revealed that the endometrial environment may also play an important role in the establishment of placental and transplacental PRRSV infections. PRRSV-positive cells were not observed in the endometrial tissues adjacent to eleven fetuses of one sow that was intranasally inoculated with PRRSV at 70 days of gestation and sampled at 80 days of gestation, despite maternal viremia and the presence of endometrial CD163+ and Sn+ cells. In contrast, PRRSV efficiently replicated in the endometrium/placenta collected from sows intranasally inoculated with PRRSV at 90 days of gestation and sampled at 100 days of gestation. Altogether, the still unknown factors that prevent or block PRRSV replication in the endometrium and the not sufficient number of susceptible cells in the placenta might join forces and cause resistance to placental/transplacental PRRSV infection before 90 days of gestation.

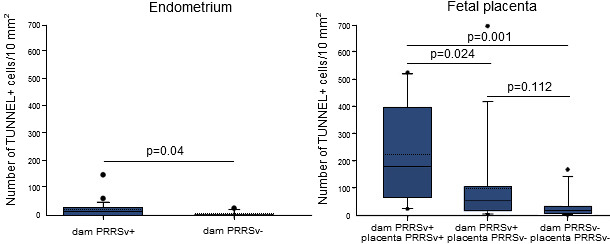

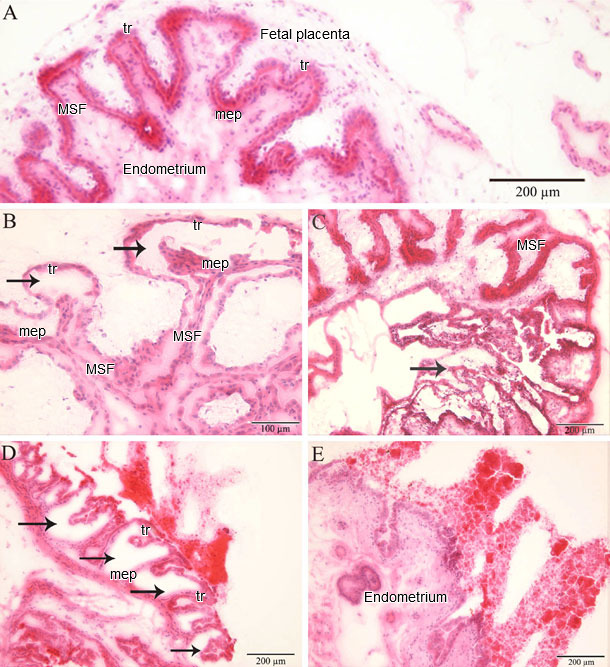

In a recent study, PRRSV-positive and apoptotic cells were identified, localized and quantified in the endometrium/placenta from three sows inoculated at 90 days of gestation and euthanized 10 days later. At 10 days post inoculation, challenged sows were viremic and PRRSV spread from mother to fetus was detected in all of them. In inoculated sows, PRRSV replication was detected in the endometrium and placenta via a specific immunofluorescence staining. The number of PRRSV-positive cells in the placenta (1-289/10 mm2 of tissue) was significantly higher than in the endometrium (1-16/10 mm2 of tissue; p = 0.004). The amount of apoptotic cells was significantly higher in the PRRSV-positive endometrium from inoculated sows versus virus-negative tissues from control sows (Figure 1). The amount of apoptotic cells increased significantly in the PRRSV-positive placentae compared to the PRRSV-negative placentae. The main conclusion obtained from the study is that PRRSV replicates in the endometrium/placenta and causes apoptosis of local cells in late gestation. Already at 20 days postinoculation, severe histopathological lesions, which range from local separation between the uterine epithelium and trophoblast to complete degradation of the fetal placental mesenchyme, are observed in virus-positive tissues (Figure 2). These histopathological lesions are incompatible with fetal life, since the integrity between the maternal and fetal counterparts within the maternal-fetal interface is crucial for in utero gas (O2/CO2) exchange, feeding and clearing of toxic metabolites of the progeny.

Figure 1. Quantification of apoptotic cells in the endometrium and placentae collected from

dams inoculated with PRRSV at 90 days of gestation and non-inoculated ones

Animals were sampled at 100 days of gestation. Solid and dotted lines are median and mean, respectively. Each box represents 25–75% of observations. Whiskers below and above the box represent the 10th and 90th percentiles. Dots below or above the whiskers on each box represent outliers not included between 10 and 90% of observations. Differences were considered statistically significant when p≤0.05. (Karniychuk et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Histopathology in the endometrium and placenta

(A) Fetal implantation sites from a PRRSV-negative fetus without microlesions (MSF: maternal secondary fold; mep: uterine (maternal) epithelium; tr: trophoblast). Fetal implantation sites from PRRSV-positive fetuses with microlesions: (B) a focal detachment of the trophoblast from the uterine epithelium; (C) a focal degeneration of the fetal placenta; (D) a multifocal degeneration of the fetal placenta; and (E) a full degeneration of the fetal placenta. (Karniychuk et al., 2012).

At present, vaccination is considered as the principal method to control and treat PRRSV infection. In a recent study, an experimental killed PRRSV vaccine, produced using a new quality-controlled viral inactivation procedure and applied with a suitable adjuvant, was tested. The results showed that the new inactivated vaccine is able to prime the virus neutralizing (VN) antibody response and to slightly reduce the duration of viremia in gilts. It also reduces the number of PRRSV-positive fetuses, and improves fetal survival. Positive effects were most probably achieved via reduction of the virus transfer from the endometrium (the primary site for PRRSV replication prior to conceptus infection) to the placenta, because the number of PRRSV-positive cells in the placentae was significantly higher in unvaccinated versus vaccinated gilts. This vaccine may be recommended for use in endemically infected farms alone or in combination with other vaccines to reduce losses due to PRRSV infection in pregnant sows. The aim is to activate the VN antibody response before 80 days of gestation, when sows become susceptible to placental/transplacental infection. Vaccination of gilts with a live vaccine before insemination or during the early stage of gestation with subsequent boosting with the new inactivated vaccine may offer new perspectives for the prevention of PRRSV-induced reproductive disorders.