The global swine industry has experienced major changes in the last 30 years. Small single-site farrow-to-finish farms operated by owner have consolidated into large multisource three-site production systems. Consumer’s demand of high quality but low cost pork has stimulated high culling and replacement rates, less labor and veterinarians per pig as well as long distance and frequent pig transportation. Today’s decisions have the potential to impact more pigs, farms and regions than ever before. For this reason, the opportune identification of the cause and dynamic of diseases is critical for the profitability and sustainability of the business.

The continuous genetic change and the high frequency of transmission between farms make of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) an extremely difficult agent to track. Monitoring is defined as the routine collection of information on disease and productivity in a population. Surveillance, in contrast, is a more intensive form of data collection that includes the gathering, recording and analysis of data as well as the dissemination of information to interested parties so that actions can be taken to control disease (Thrusfield, 2005). The term surveillance has been used in this article because the ultimate goal of swine practitioners is to take actions to prevent or control diseases.

When designing a PRRS surveillance program for a farm, company (system) or region, the number of samples, the diagnostic test, the collection method, the age of sampled individuals, the desired confidence level and the frequency of testing are defined based on:

- Production goal: the cost of failing or delaying the detection of PRRSV in a boar stud or genetic multiplier is much higher than in a commercial herd; therefore, the desired confidence level and therefore the number of samples needs to be higher for a multiplier (Table 1).

- Risk of disease introduction: biosecurity, local pig density and PRRSV prevalence in the area, influences the frequency of testing. Samples need to be collected more often when the risk is higher. Alternative collection methods such as ropes for oral fluids are recommended when more intensive programs are implemented.

- Previous infection or vaccination status: PRRSV is easier to identify in negative populations than in previously infected or vaccinated herds. Because under high risk conditions, maintaining herd immunity conferred by wild-type or modified-live PRRSV exposure is recommended, surveillance protocols need to accommodate this need.

Table 1. Number of individual samples required to detect at least one positive at various confidence levels and expected prevalences (Epi-Tools).

| Confidence level | ||||

| 80% | 95% | 99% | ||

| Expected prevalence | 1% | 162 | 302 | 463 |

| 5% | 32 | 60 | 91 | |

| 10% | 16 | 29 | 45 | |

| 30% | 5 | 9 | 14 | |

Collecting and testing clinical samples to detect and differentiate PRRSV as well as gathering and analyzing the epidemiological information related to each case, represents a considerable investment by pork producers and their veterinarians. To justify the investment, results must generate useful information that could lead to reduction of risk, evaluation of interventions and/or the adjustment of control programs. The main components of a PRRS surveillance program include:

1.- Defining objectives

Minor differences can be expected between farms, companies or regions, but generally the programs aim to:

- Facilitate the rapid detection of PRRSV introduction

- Provide opportune information to attempt to contain outbreaks and minimize losses

- Identify the most likely source of infection, and/or

- Analyze the evolution of PRRSV prevalence and genetic diversity in system or region

2.- Optimizing the use of available resources

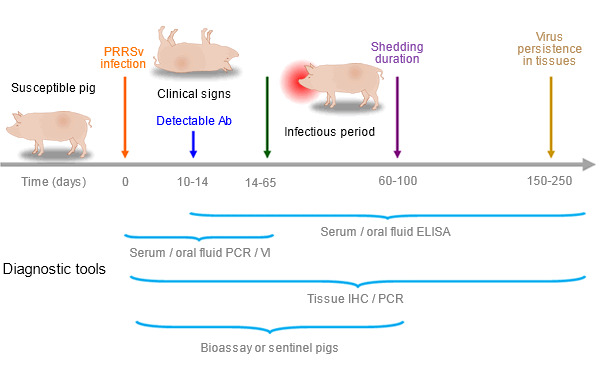

Allocating an adequate budget for disease surveillance is not an easy task. “Do not collect any sample or perform any test which results will not affect the current course of actions”. Significant differences in the availability of diagnostic tests can be found between countries, but it is critical to consider the strengths and limitations of the tests and sample types under different situations (Figure 1). Diagnostic assays detecting PRRSV antigen include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on serum, semen, oral fluids, environment, aerosol or tissues, virus isolation (VI) from serum, oral fluids, semen, aerosol or tissues and immunohistochemistry (IHC) on lymphoid tissues or lungs. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has been adopted as the standard serologic test to detect antibodies against PRRSV in serum and oral fluids. None of those tests by itself is able to accurately determine the shedding status of a population, bioassay or exposure to sentinel pigs is the most adequate method to assess shedding (Figure 1). Today, swine practitioners usually request PRRSV open reading frame (ORF) 5 nucleotide sequencing on one PCR-positive serum or oral fluid sample per case to identify the PRRSV isolate present in the herd.

Figure 1. Ability of diagnostic tools to detect PRRSV antigen or antibodies during infection

A common practice in North America includes testing (a) negative gilts or growing pigs with ELISA on oral fluids, (b) positive or vaccinated gilts or growing pigs with PCR on oral fluids, (c) negative breeding herds with ELISA on individual serum samples from sows and (d) positive, vaccinated or stable breeding herds with PCR on pooled serum samples from due to be weaned pigs.

3.- Identifying indicators of risk and disease

Today, the complexity of the swine industry and the need for useful information demand the implementation of comprehensive surveillance programs that measure:

- Incidence: number of new cases (new PRRSV introduction to a herd) detected in a region or company during a period of time.

- Prevalence: proportion of infected herds in a region or company at a point in time.

- Risk: the probability of a new PRRSV introduction to a susceptible herd at a given time. Although difficult to estimate, significant efforts have been conducted to asses risk through biosecurity questionnaires (http://vdpambi.vdl.iastate.edu/padrap/default.aspx).

- Genetic diversity: representation of any PRRSV isolate identified in a company or region.

4.- Monitoring protocol

Herd-level sensitivity (HSe) is the probability of detecting a positive case from an infected herd and herd-level specificity (HSp) is the probability of obtaining a negative case from a non-infected herd. Both HSe and HSp are affected by the individual-test Se and Sp, the number of tested animals and the true prevalence of infection in the herd. In most of the situations faced in swine medicine a high HSe protocol at a “reasonable” cost is desired.

Valuable information that can indicate the change of infection status in a population mainly comes from three sources:

- History: verified information indicating events such as vaccination, intentional wild-type virus exposure, reception of pigs with known PRRSV infection status, etc. This knowledge allows for the strategic allocation of resources when delivered accurately and opportunely.

- Contingent (passive) surveillance: self reporting diagnostic results triggered by clinical signs. Care taker calls the veterinarian when abnormal parameters are observed. Serum, oral fluid and/or tissue samples are collected during the “emergency visit” to be tested by PCR and/or ELISA.

- Regular (active) surveillance: periodical diagnostic results indicating the presence or the absence of PRRSV in the herd. See an example in Table 2.

Table 2. Example of sampling-testing protocol for PRRSV regular surveillance

| Herd type | PRRSV infection status (AASV) | Age of pigs / frequency | Sample type | Number of samples | Diagnostic test |

| Breeding (farrow-to-wean) | Negative (IV) | Adults / quarterly | Serum | 10-30 | ELISA |

| Stable (II) or Positive (I) | Due to be weaned piglet / monthly | 30-60 | PCR & Sequencing | ||

| Breeding (farrow-to-finish) | Negative (IV) | Adults / quarterly | Serum | 10-30 | ELISA |

| Stable (II) or Positive (I) | 6-10 week-old pigs / monthly | Oral fluid | 30-60 | PCR & Sequencing | |

| Nursery or Finisher | Negative (IV) | 4 weeks post placement for all-in/all-out or quarterly for continuous flow sites | Serum | 10-30 | ELISA |

| Oral fluid | 1-4 ropes / 1000 pigs or air space | ||||

| Positive (I) | Serum | 10-30 | PCR & Sequencing | ||

| Oral fluid | 1-4 ropes / 1000 pigs or air space |