PRRSv continues to be a challenge for the US swine industry, costing the industry from $560 (2005) – $664 (2013) million/year. The Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project (MSHMP), showed a 24% incidence of new breaks during the 12-month period monitored (July 2020 – June 2021). Laboratory data shown as part of the Swine Disease Reporting System (SDRS) has verified from a diagnostic perspective, that a rising number of new PRRS introductions into herds are that of the RFLP 1-4-4, Lineage 1C variant, a strain associated with higher viral numbers.

Biosecurity and bio-exclusion are of particular importance in the prevention and control of PRRSv to avoid a herd infection. Sow herds located in increasingly pig dense areas break at a greater frequency. This increased frequency of infection is associated with the number of surrounding finishing populations. Filtration has been shown to successfully reduce the frequency of PRRSv introductions into sow herds. Feed mitigants have been used as a tool to limit the risk of new virus entry into a farm as well. An often-forgotten part of biosecurity is biocontainment, the concept of limiting the spread of virus as much as possible from an infected population, and is an area that we need to continue to reduce area spread as well.

Clinical signs of this strain were consistent with what has been previously described for PRRSv virus, including increased rate of abortions, reduced farrowing rate, and an increase in sow mortality, stillborn, and mummy rate and preweaning mortality. Post-weaning, the virus led to a reduction in average daily gain (ADG) and increased mortality, particularly in the nursery phase.

The difference with the PRRSv 1-4-4 L1C is the magnitude and length of signs observed. There does appear to be cross protection from previous exposure to other viruses and vaccines; it appears to allow herds to stabilize and return to negative pig flow faster. Diagnostically this virus is like previous viruses with the PCR-based test working well. The one thing that has been different with these viruses is the much lower CT (cycle threshold) values observed in some herds, indicating relatively higher viral loads in these affected animals.

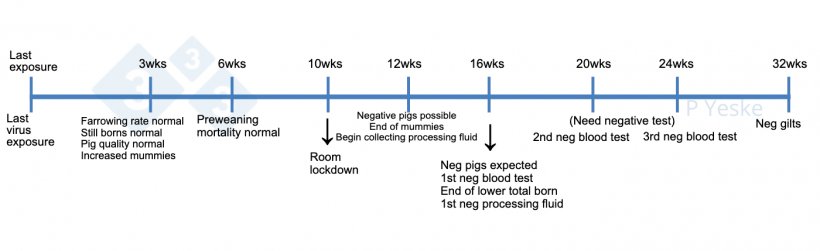

Control measures follow those we’ve used for previous PRRSv strains, and include allowing a farm to stabilize and then move forward with virus elimination utilizing a load, close, and expose protocol. Farms with an onsite gilt developer are set up to do this the easiest. Ongoing monitoring of the process has become easier and better at detecting low prevalence herds with the use of processing fluids. Due to wean pigs need to continue to be monitored to be sure that you don’t miss infection occurring in the farrowing barn. Herds have returned to negative status and with an increased time to low prevalence.

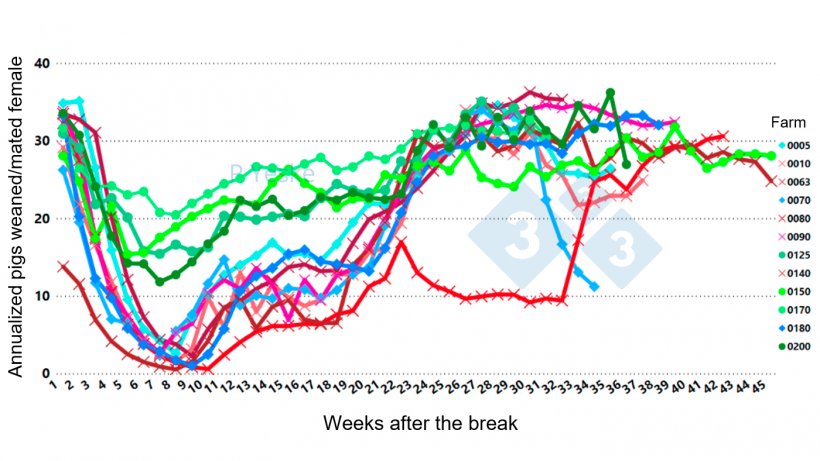

Figure 2 shows the changes in annualized pigs weaned/mated female over time on twelve breeding herds in the U.S. that had outbreaks between November 2020 to July 2021 with similar PRRS viruses, all of which maintained greater than 98% homology on ORF 5 sequencing.

It appears that PRRS 1-4-4 1C variants act similarly to other PRRS viruses we have experienced in the past. Severity of the outbreak depends on existing herd immunity, how quickly the virus moves through the herd, and the amount of time from outbreak to closure. Due to all these factors, this is why we see the different outcomes in various herds. Herds have eliminated this virus successfully and returned to baseline production both in the sow herd and wean to finish.