Introduction

Sow performance records are important for the evaluation and monitoring of commercial production levels. Swine producers aim to wean a large number of pigs per litter by increasing the number of piglets born alive, reducing the number of stillbirths and maximizing the survival of the piglets to weaning. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the relationships amongst piglet weaning weights and survival traits with the number of piglets allowed to nurse in purebred and crossbred litters.

Methods

Data were collected from US purebred swine producers:

| Breed | Number of litters |

| Duroc | 29,297 |

| Landrace | 34,177 |

| Yorkshire | 40,301 |

| Yorkshire sire x Landrace dam | 8,061 |

| Landrace sire x Yorkshire dam | 4,028 |

Sow productivity traits were:

- Number born alive

- Litter birth weight

- Number of pigs after transfer (NAT)

- Number of pigs weaned (NW)

- Preweaning survival percentage (calculated as NW/NAT x 100)

- Litter weaning weight (LWW) (only piglets that were fully formed, live piglets)

- Piglet weaning weight (the mean was calculated as LWW/NW)

- Weaning weights were adjusted to 21 days of age

The data was distributed into 4 time periods of 1986 through 1997, 1998 through 2002, 2003 through 2008, and 2009 through 2011. After initial analysis it was found the period 1 and period 2 as well as period 3 and period 4 were not significantly different and were combined to yield 2 time periods from 1986 through 2002 and 2003 through 2011.

Results

The individual breed means are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Means and standard deviation (SD) of sow productivity traits by breed or cross.

| Trait | Duroc | Landrace | Yorkshire x Landrace |

Landrace x Yorkshire |

Yorkshire | Overall means |

| Litter weaning weight | 50.4 (12.8) |

65.6 (13.6) |

69.3 (11.0) |

62.3 (14.9) |

66.4 (14.9) |

59.57 |

| Piglet weaning weight | 6.3 (1.2) |

6.8 (1.1) |

7.0 (0.6) |

6.6 (1.2) |

6.7 (1.1) |

6.51 |

| Number piglets born alive | 9.1 (2.2) |

10.6 (2.7) |

10.9 (2.7) |

10.7 (2.8) |

10.6 (2.9) |

10.20 |

| Litter birth weight | 15.5 (3.8) |

17.8 (4.3) |

15.8 (3.6) |

16.9 (4.4) |

16.3 (4.2) |

16.51 |

| Survival % | 90.8 (12.0) |

91.7 (10.5) |

91.9 (9.8) |

90.9 (11.6) |

91.4 (11.6) |

91.2 |

| Total piglets born | 10.0 (2.3) |

11.4 (2.8) |

11.8 (2.9) |

11.6 (3.0) |

11.6 (3.0) |

11.06 |

Other overall means were 9.18 piglets weaned per litter and 1.64 kg for piglet birth weight.

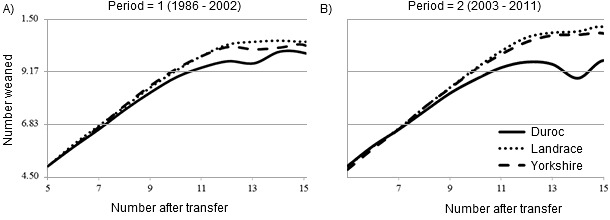

For both periods, number weaned for smaller litters (less than 10 pigs after transfer) were not significantly different among breeds (Figure 1, P > 0.05). As the number of piglets after transfer increased, the numbers of piglets weaned from Landrace and Yorkshire dams were greater (P < 0.05) than Duroc litters. Maximum numbers of piglets weaned in period 2 (Figure 1B) was achieved at 15 piglets after transfer for all breeds (9.68 for Duroc, 11.18 for Landrace, and 10.89 for Yorkshire.

Figure 1. Relationship of number after transfer with number weaned [1986 to 2002(A); 2003-2011 (B)] by breed.

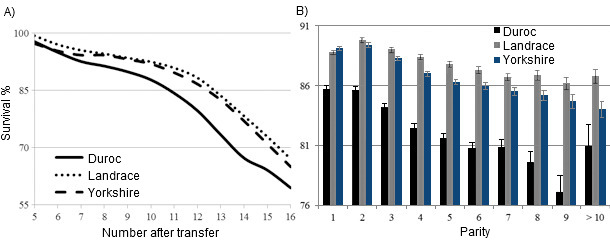

Over the entire range of number of piglets after transfer, preweaning survival ranged from nearly 100% (NAT =5) to 59.5% for the Duroc breed with 16 piglets after transfer (Figure 2A). Preweaning piglet survival decreased in a linear fashion until then it continued to decrease at an increasing rate as number after transfer increased above 11. Parity 2 litters had the greatest preweaning survival rates (P < 0.05) and as parity increased preweaning survival decreased (Figure 2B). These results are in agreement with previous studies by Cecchinato et al. (2010) that found a similar relationship with parity 2 dams having the highest preweaning survival with decreased preweaning survival as parity increased for both crossbred and purebred litters.

Figure 2. Effect of number after transfer (A) and parity (B) on survival percentage by breed.

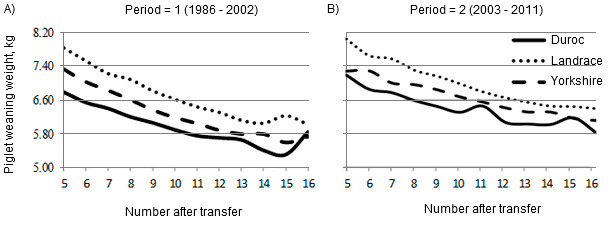

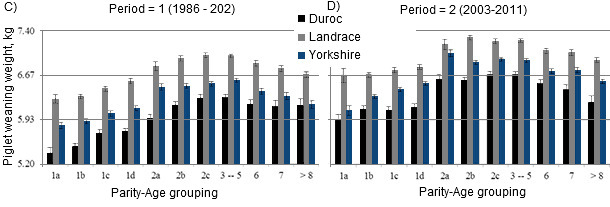

Average piglet weaning weight was affected by several factors including sow breed, number after transfer, time period and parity- age class (Figure 3). As the number of pigs after transfer increased, mean piglet weaning weights decreased in a linear fashion. Pigs from Landrace litters (6.84 kg) were heavier than Duroc (6.16 kg) and Yorkshire (6.48 kg) pigs over the entire range of number after transfer (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Effect of number after transfer [1986 to 2002 (A), 2003 to 2011 (B)] or parity [1986 to 2002 (C); 2003 to 2011 (D)] on piglet weaning weight in purebred litters by breed.

Crossbred Yorkshire- Landrace litters in the study (P < 0.05) had greater litter and piglet weaning weights than purebred Yorkshire and Landrace litters. Crossbred litters exhibited approximately 11.6 % heterosis in litter weaning weight and 9.1% in piglet weaning weight.

Discussion

Piglet survival is an outcome of very complex interactions between the piglets, the sow, and the environment in which the animals are raised (Edwards, 2002). Increasing the survival of pigs to weaning when 13 or more piglets are allowed to nurse requires a combination of genetic selection and management changes. Selection for increased piglet birth weight and decreased within litter variation in birth weight has been suggested (Knol et al., 2010). Piglet birth weight as a trait of the sow (maternal trait) has a heritability of about 15 %. Piglet birth weight as direct effect is only about 4 % heritable. Using estimated breeding values selection for increased mean piglet birth weight relative to the total number of piglets born has potential to increase uterine capacity. The within litter variance for piglet birth weight is less heritable (5 to 8 %) and will be more difficult to realize substantial genetic progress than piglet birth weight. Selection of young maternal line boars based on genomic information will increase the rate of genetic progress for these traits. Although piglet birth weight is the most influential factor affecting piglet survival other behavioral factors such as vitality and vigor of piglets at birth contribute to the overall likelihood of the offspring surviving (Baxter et al., 2010; 2013). The mothering ability, the ability of the sow to care for her piglets is heritable and can respond to selection. These vitality and vigor traits are due to direct genetic effects and can be selected for in both the maternal and terminal sire lines.

There has been an increase in number born alive and the result is an increase in both number weaned and preweaning mortality (Knauer and Hostetler, 2013). As litter size increases, the proportion of light piglets at birth and weaning increases, resulting in more pigs having their long-term robustness impaired (Rutherford et al., 2013). With selection for increased number of piglets born alive per litter, resulting in greater number of sows nursing 12 to 14 pigs, greater relative emphasis must be placed on preweaning survival in the selection objective. Lightweight piglets have less energy reserves and less ability to maintain body temperature immediately after birth. So more intense management including increased farrowing room temperatures (24 to 25 ºC), drying of the newborn piglets, use of split sucking, hot boxes and supplemental colostrum products have to be considered.

Increasing litter size can result in reduced pig post-weaning performance. Heavy pigs at weaning tend to grow faster (Lawlor et al., 2002) than their lighter counterparts. Lighter pigs at birth and weaning tend to grow more slowly, be less feed efficient, have slightly decreased carcass lean percentage, and have a greater mortality rate from weaning to market than heavier pigs at birth and weaning (Fix et al., 2010a,b; Schinckel et al., 2009; 2010).

Conclusion

It is important that these relationships of the sow productivity traits and factors including parity, breed-cross and number after transfer be evaluated to refine selection and management practices. The number of piglets born alive has been improved via genetic selection. Greater emphasis should be placed on the genetic improvement and management strategies to increase preweaning survival (Knol et al., 2010).