Gilt selection and management

Replacement gilts are expensive and need to be managed for both fertility and longevity. Usually, a gilt needs to deliver at least three good sized litters in order to pay for herself. Thereafter, each litter is increased profit.

Gilt fertility management starts in the farrowing house, by identifying potential replacement gilts. Future breeding gilts should be selected from a larger litter (eg. ≥ 12 live born) since their sow has demonstrated good fertility. However, in order to realise their own fertility potential, gilts should be raised in a smaller litter (eg. < 8 piglets). This also ensures gilts get better access to colostrum which, in addition to improving passive immunity, may reduce gilt age at puberty and increase first litter size. Gilt average daily gain (ADG) to puberty also needs to be monitored to avoid extremes, as gilts bred > 130 kg at < 175 days are at increased risk of culling due to leg problems and gilts bred < 130 kg at ≥240 days are too small and are less likely to survive in the herd.

Why induce puberty?

Knowledge of when gilts are ready to breed is essential for effective gilt pool management. If an appropriate number of service-ready gilts are not available in any breeding week, the breeding target may be missed resulting in a very expensive empty farrowing crate later. To get predictability of gilt availability requires some form of puberty stimulation to both induce and synchronise the pubertal estrus.

How do I induce an earlier puberty?

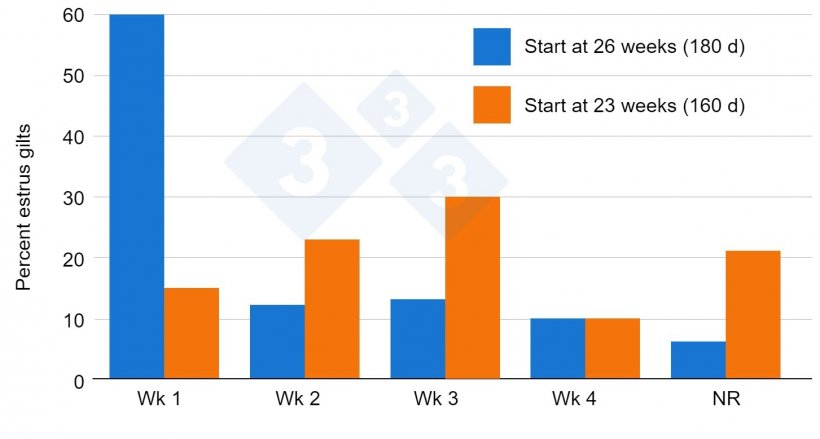

The most common method of puberty stimulation is boar exposure, which was covered in a previous 333 article by Rob Knox, and dealt with the ‘gold standard’ approach of daily movement of gilts to the boar. The only drawbacks of this are the daily labor requirement for pig moving and that many gilts show a relatively tight synchronous estrus in a short period of time, but then only a few are needed in each of several consecutive breeding weeks. To counter this, use 24/7 boar contact from about 20-24 weeks (ie. market age), either housed together with a sterile boar, or fenceline contact. Housed boar age should be about 10 months while fenceline boars can be much older if wanted. Remove the boar at 27-28 weeks and start daily contact. Pubertal estrus will then be more widely distributed (see Fig. 1).

- If the gilt is in estrous within 14 days, skip her and breed at the next estrus.

- If estrous after 14 days, breed her.

- If estrus is not detected by 21 days, cull her.

Interestingly, being raised in a small litter and having boar exposure from about 20-weeks significantly improved gilt fertility and herd longevity.

Using hormones to induce puberty

If boar exposure is not giving the expected results, for example during the hotter months, then puberty can be induced using gonadotrophins. These include:

- Equine chorionic gonadotrophin (eCG), that has primarily an FSH-like activity (but some LH-like activity).

- Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), that has only LH-like activity.

In swine, LH becomes the primary stimulus for medium-sized follicles to grow to ovulation, unlike cows where FSH (or eCG) will stimulate ovarian follicle growth to the point of o vulation, For this reason, puberty induction in female pigs will require both eCG and hCG, although eCG may work in weaned sows.

The usual combination is:

- Gilts: 400 IU eCG + 200 IU hCG.

- Seasonal infertility in sows but not gilts: 400 IU eCG + 400 IU hCG would likely work better.

After treatment, females are expected to show signs of estrus by day 4 to 6.

If hormones are to be used, the timing of treatment will depend on why you are using them.

Not enough females to breed in a particular week

If you anticipate some future empty farrowing crates, which as stated previously are very expensive, you can take some measures. Inject gilts known to be prepubertal (eg. even if only 140-150 days old and a market gilt). If they bred successfully you can expect smaller litters, but this is better than no litter, and she should be culled at weaning.

Are too many of your older gilts not showing estrus?

If this is the case, then either:

- Gilts are having ‘silent’ heats (very unlikely)

- Gilts are cyclic but estrus was not detected (most likely)

- Gilts are truly anestrus (possible).

If a gilt is cyclic she will not respond to gonadotrophins. She may actually ovulate but the progesterone already in her blood will totally suppress estrus behaviour and so, effectively, she will not respond.

If she is truly anestrus, she may be stimulated to come into heat. This pattern of response is well illustrated in Table 2, where non-estrus gilts were sent to slaughter and their ovaries examined to confirm their status; 60% of apparently anestrus gilts were actually cyclic. This illustrates that, whether using boar exposure alone or gonadotrophins, good estrus detection management is vital.

| Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Total gilts | 175 | 100 |

| Prepubertal | 68 | 39 |

| Pubertal (Corpus Luteum) | 62 | 35 |

| Post-pubertal (Corpus Luteum + Corpus Albicans) | 45 | 26 |

Stancic et al. (2011)

As a rule-of-thumb, Figure 2 provides a decision tree regarding the fate of gilts receiving hormone treatment to induce estrus.

It is important to note that most gilts will have the potential to become productive sows. The selection process is designed to weed out the least fertile gilts and to promote the performance of the remaining gilts so that they will express their fertility potential.