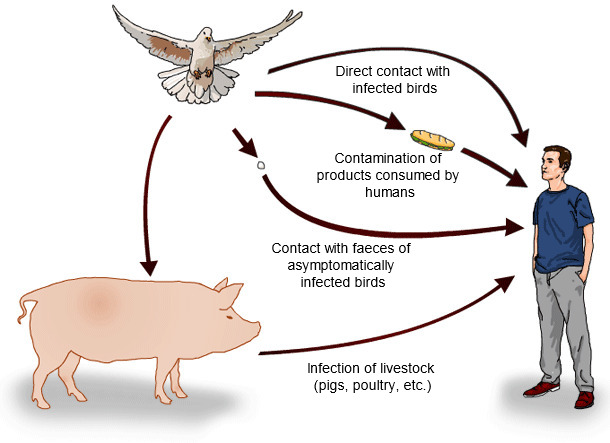

Wild birds are possible sources of salmonellosis for humans and other animals. They can become infected with this pathogen from contaminated environments and further transmit it to humans (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Possible transmission routes of Salmonella spp. from wild birds to humans.

There are evidences of the role played by wild birds in the contamination of feed and in salmonellosis outbreaks in livestock, but few studies have evaluated the relationship between bird and pig salmonellosis. The role that these birds may play in the infection of swine will differ from one region to another, depending on the existing epidemiologic situation.

Image 1. Possible contamination sources of the feed with Salmonella spp. due to wild birds.

Which role could wild birds be playing in the pig salmonellosis in a high-prevalence country like Spain?

Subclinical salmonellosis in wild birds

The prevalence of salmonellosis in wild birds is generally low, but some factors have an influence on it (Table 1).

Table 1. Factors potentially associated with the prevalence of Salmonella spp. in wild birds.

| Factor | Higher risk | Lower risk |

| Season of the year | Winter | Rest of the year |

| Kind of feeding | Birds of prey Insectivorous birds |

Birds not of prey Granivorous birds |

| Feeding habits | On the ground | On hanging feeders |

| Migration habits | Short distances | Long distances |

| Surrounding | Urban surroundings Farming surroundings |

Natural surroundings |

We have recently studied the importance that the factor "farming surrounding" could have on the distribution of salmonellosis in wild birds. In order to do it, during 2 years faecal samples of 1,052 birds belonging to more than 50 different species (mainly passeriform birds: sparrows, starlings, swallows, warblers, wagtails, etc.; and columbiform birds: pigeons) captured near pig farms and in natural environments far from the farms were taken (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in faecal samples of wild birds.

| Origin of the birds | No. of analysed samples (no. of birds) | No. of + samples | Prevalence (%) |

| Natural environment | 431 (581) | 2 | 0.46 |

| Near the pig farm | 379 (921) | 13 | 3.46 |

| TOTAL | 810 (1,502) | 15 | 1.85 |

Salmonella spp. were isolated in 1.85% (15) of the analysed samples. Thus, it could be expected that the risk of wild bird-related salmonellosis would be quite limited. However, when the origin of the birds was considered, the proportion of Salmonella positive samples was significantly higher when the samples came from birds captured near pig farms.

After adjusting by the factors shown in Table 1 and the number of birds that contribute to each of the faecal samples, the probability of finding a sample contaminated with Salmonella spp. was 16.5 times higher (95% confidence interval = 5.2-52.6) when it came from birds captured near pig farms, as compared with samples from birds captured in areas far away from the pig farms. According to the confidence interval, this probability could even be 50 times higher.

Relationship between the strains isolated in wild birds and swine

In 9 (21.4%) of the 42 farms in which birds were captured Salmonella spp. was isolated from bird faecal samples. More than half of these farms had also been Salmonella-positive when pig faecal samples were analysed.

In 44% of the farms in which Salmonella spp. was isolated from both pig and bird faecal samples, a clear phylogenetic relationship was seen between the strains from pigs and those from birds, confirming the transmission of Salmonella spp. between birds and livestock. The most frequent Salmonella serotype in birds and pigs was Typhimurium.

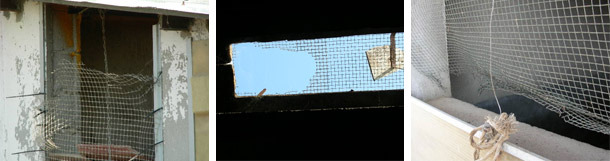

In some of the farms several bird species infected with Salmonella spp. were identified (sparrows, starlings, and swallows), and the genetic pattern of the different isolated strains was exactly the same, and similar to the one seen in pigs. This relationship was seen mainly in farms in which a great density of birds was observed or in which the birds entered easily into the premises (images 2, 3, and 4).

Image 2. Presence of a great density of birds in a pig farm.

Image 3. Left: Walls with plenty of birds faeces: a clear evidence of the constant entry of birds into the building. Right: Detail of the floor of the fattening/finishing area contaminated with wild birds' faeces after its cleaning and disinfection.

Image 4. Damaged meshes against birds, a very common error in the biosafety measures at the farm.

Birds: victims or responsible for the infection in pig farms?

In order to answer this question, the resistance profiles to antimicrobials (RA) for all the isolated Salmonella strains were analysed. It was expected that if the strains came originally from the wild birds they did not have RA patterns or, at least, they did not fit in with those seen in pigs. It is estimated that 80% of the isolates from pigs have RA.

The great majority (94.4%) of the Salmonella strains isolated from pigs showed RA (Table 2). On the contrary, the strains from wild birds were mainly sensitive to antibiotics (74%), and when they had RA, the pattern generally fit in with the one seen in the Salmonella strains isolated from pig samples from the corresponding farm.

Table 2. Prevalence of the resistance to antibiotics in Salmonella spp. isolates from birds and pigs.

| + samples | Resistant (%) | Multiresistant* (%) | |

| Swine | 54 | 51 (94.4) | 50 (92.6) |

| Birds | 27 | 7 (26) | 6 (22.2) |

*Against more than two antibiotics

Only on two farms all the Salmonella strains isolated from pigs were sensitive to all the tested antibiotics. On these two farms, the Salmonella strains isolated from birds were also sensitive to all the tested antibiotics.

Conclusion s

- Pig farms would act as facilitators for the transmission of salmonellosis among wild birds, regardless of the primary origin of the infection (birds or pigs).

- The degree of bird density on the farms could have a lot to do with the transmission of the infection, because the genetic relationship observed among the isolates from different bird species was only seen in farms in which the birds were abundant.

- The observation of the same Salmonella strain in pigs and wild birds captured on those farms shows the need for increasing the biosecurity measures on the farms that prevent the direct contact between birds and pigs.

- The role that wild birds can play in the transmission of this disease cannot be underestimated.